Better-regulated digital money tokens are the real threat to the financial system.

Last week’s Terra ($UST) collapse was hardly surprising: backed by little but hot air and an online cult, the cryptocurrency was an accident waiting to happen.

But it’s stablecoins with real reserves that pose a much bigger challenge for regulators. And that’s because they are part of a growing sector of private money-like instruments that threaten chaos if they go wrong.

Money market funds pose risks to the system

Although the way they operate is different, stablecoins closely resemble money market funds (MMFs), a financial instrument invented in the 1970s.

Both MMFs and stablecoins gained popularity as a way around the financial system’s rules: MMFs offered interest rates above those on US bank deposit accounts, which were capped at the time; stablecoins allowed cryptocurrency market participants to access dollars without having a bank account.

But MMFs—a $9trn industry—have always been prone to destabilising runs. And when they break the buck (lose their peg to the dollar or other fiat currency), they threaten chaos.

it’s stablecoins with real reserves that pose a much bigger challenge for regulators

According to a recent staff report from the New York Fed, runs from MMFs have occurred in many countries and under many regulatory regimes since 2000, despite repeated attempts to shore up the money market fund rules.

When Lehman Brothers failed on September 15, 2008, some prime MMFs were holding its debt, and investors redeemed more than $300bn (15 percent of assets) from those funds in the next five days, the NY Fed said.

Outflows only abated when the US Treasury guaranteed virtually the entire MMF industry and the Federal Reserve provided liquidity using its emergency powers.

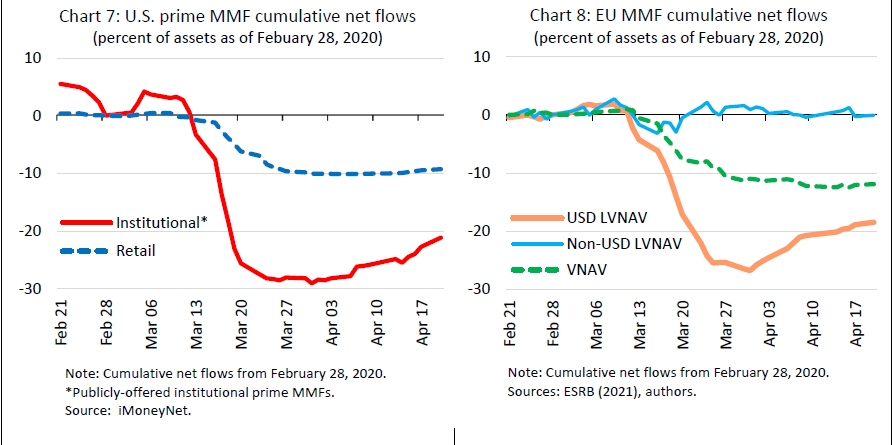

Runs from MMFs occurred again in 2011 during the eurozone crisis (when US funds that were exposed to faltering European banks started experiencing heavy outflows), in 2013 in China (when MMFs had outflows of nearly 40 percent of AUM in the second quarter) and in 2020 amidst the coronavirus market panic.

2020 run from US prime institutional MMFs

According to the NY Fed, the risks in money market funds can only be addressed in one of two ways.

Either regulators should force MMFs into the investment fund sector, where there are established mechanisms for preventing investor runs: these include the ability by a fund issuer to delay redemptions, impose ‘gates’ (where investors can only redeem a fraction of their shares) or introduce ‘swing pricing’ (where MMFs have separate prices for purchases or sales).

Or, the NY Fed says, regulators should establish protections for MMFs similar to those for deposits: in other words, MMF holders would benefit from deposit insurance guaranteeing redemption at par for a minimum holding size. But this insurance would come at a cost which might render many MMF business models unviable.

Replay in stablecoin sector

All these arguments are now being replayed in the $180bn stablecoin sector.

According to the Bank of England, which devoted a special report to cryptoassets in its March Financial Stability Report, regulators around the world are taking different approaches when confronting the potential risks in these digital currency tokens.

In the US, the President’s Working Group published a report in November 2021 which included an initial recommendation that stablecoins should be required to be issued by insured depository institutions, the Bank of England noted.

In the EU, the draft Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation aims to capture stablecoins via a modified version of the e-money framework, the Bank said. E-money is a form of digital cash that is not backed by state deposit insurance schemes.

And in the UK, the Bank of England said, “stablecoins used as money-like instruments in systemic payment chains should meet equivalent standards to commercial bank money in relation to stability of value, robustness of legal claim and the ability to redeem at par in fiat”.

One important protection for commercial bank money is the backstop to compensate depositors in the event of [bank] failure, the Bank went on.

However, the Financial Policy Committee said, it might not require stablecoin issuers to copy banks and offer deposit insurance.

“The FPC judges that, at this stage, a systemic stablecoin issued by a non-bank without a resolution regime and/or deposit guarantee scheme could meet its expectations, provided the Bank applied a regulatory framework that was designed to mitigate risks to financial stability,” it said in its March report.

Stablecoin reserves and settlement

Last week’s Terra collapse may force a rethink and push central banks and regulators to apply more stringent standards.

According to IMF economist Manmohan Singh and Caitlin Long, CEO of Custodia Bank, the ability of stablecoins to settle nearly in real time means they should hold only the highest quality collateral—in the form of central bank reserves.

In a Risk article (paywalled) published after the collapse of Terra, Singh and Long said that US rulemakers are now whittling down their list of valid methods for collateralising stablecoins, looking for those that can actually create true stability.

Recent proposals from legislators and regulators have shifted attention away from turning stablecoin issuers into insured depository institutions—the recommendation made by the US President’s Working Group on financial markets in November 2021, Singh and Long said.

“USD-collateralized #stablecoins shld be backed 100% by cash deposited at Fed. Even T-bills don’t work–bc they settle next day, but last wk a stablecoin collapsed w/in hours. Need *real-time* liquidity (only avail at Fed),” Long tweeted on May 17.

But the long-term prospects for stablecoins still appear bright. In November 2020, the Bank for International Settlements said that stablecoin volumes in future may be ‘orders of magnitudes higher’ than at the time.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, one person close to regulators’ discussions said that a battle between stablecoins and large commercial banks over digital money is likely to intensify.

“Will stablecoins become sizeable?” the person asked.

“Time will tell. If they do then we should let the market decide whether deposits at, say, JPMorgan or Citi or Barclays are better for the client, who may have zero desire to deal with stablecoins.”

In theory, stablecoins have a design advantage over bank deposits. A transfer of stablecoin ownership occurs near-instantaneously, while banks update their account balances only at the end of the day. But whether institutional clients care enough about this remains to be seen, the person said.

“Institutions may still be OK with their free float being used by a bank than [having] T0 ownership. And banks will fight stablecoins as they will lose that intraday free float,” they said.

Allowing stablecoin issuers to hold central bank reserves directly would mean opening up access to wholesale payments systems to non-banks, a step taken so far only in the UK and Lithuania.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content from New Money Review

Did Terra operators bail out crypto whales?

Third-largest stablecoin loses its dollar peg

Terra depletes reserves in stablecoin panic

Unstable DeFi could trigger wider crash