The booming decentralised finance (‘DeFi’) market suffers from an existential problem, says the Bank for International Settlements (BIS): it isn’t decentralised.

Meanwhile, the contagion risks from DeFi to the rest of the financial system are growing fast, the Basel-based institution has cautioned.

The rise of DeFi

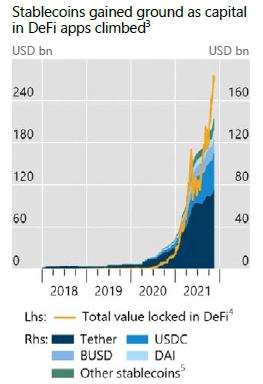

In its latest quarterly review, the BIS pointed out that DeFi is a fast-growing part of the cryptocurrency financial system. At a recent count, the value of assets locked into DeFi contracts exceeded $250bn.

Total value locked in DeFi

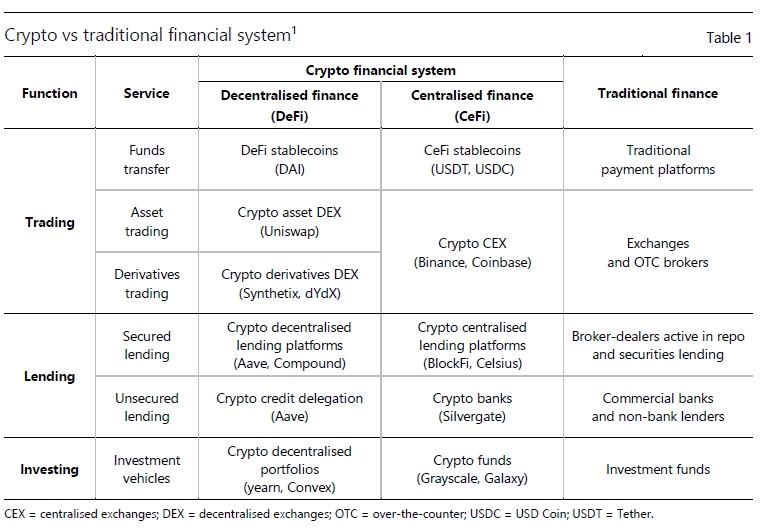

DeFi activities parallel those in the traditional financial system, such as trading, lending and investing.

DeFi includes a number of automated lending protocols, such as Aave, bZx v2, Compound, Maker, Polygon Aave and Venus. It also contains automated market making protocols, such as Uniswap, Curve, and Balancer, and automated investment vehicles, such as Yearn and Convex.

DeFi vs. CeFi

DeFi’s development has been closely associated with the cryptocurrency ethereum, which supports automated contracts with pre-defined protocols. These are referred to in cryptocurrency jargon as ‘smart contracts’.

By contrast, the original cryptocurrency, bitcoin, has only limited programmability.

In the last year, DeFi activity has also spread to other cryptocurrency networks, such as Binance Smart Chain (BSC), Solana, Terra, Avalanche and Tron, as market participants seek to escape the high transaction fees on ethereum.

According to the BIS, it recently cost as much as $160 to make a single DeFi transaction on ethereum using the Uniswap protocol.

“Full decentralisation in DeFi is illusory”

Stablecoins boom in parallel

DeFi’s rise has also been closely associated with the explosion in value of cryptocurrency ‘stablecoins’, which now total around $150bn.

Stablecoins are digital tokens designed to trade at a one-to-one value with a reference asset, such as a traditional fiat currency. Within DeFi applications, they are widely used as a medium of exchange and as collateral.

Stablecoins are largely unregulated and in November, the US central bank said in its half-yearly financial stability report that they pose a growing threat to traditional payment and financial systems.

Stablecoins closely resemble money market funds but are not subject to the same disclosure requirements.

Last week the largest stablecoin, Tether, released an attestation of its end-September assets but failed to provide details of its holdings, which include over $30bn in unsecured corporate debt.

Bloomberg reported in October that Tether’s reserves include billions of dollars in short-term loans to large Chinese companies.

According to the BIS, any lack of confidence in stablecoins would hit the DeFi sector hard.

“An evaporation of trust in stablecoins could have wide repercussions for DeFi,” the BIS said.

“Transfers of funds across investors and platforms would become more costly and cumbersome, impinging on the ‘networked liquidity’ that is a key feature of DeFi.”

DeFi is centralised after all

According to the BIS, the principal promise of DeFi—the absence of human intervention—doesn’t bear scrutiny.

“DeFi purports to be decentralised,” the BIS said.

“This is the case for both blockchains and the applications they support, which are designed to run autonomously—to the extent that outcomes cannot be altered, even if erroneous. But full decentralisation in DeFi is illusory.”

“All DeFi platforms have an element of centralisation, which typically revolves around holders of ‘governance tokens’,” the BIS went on.

These token holders, often the platforms’ software developers, can vote on proposals, not unlike corporate shareholders, the BIS said.

And other features of DeFi blockchains, such as proof-of-stake consensus mechanisms, favour the concentration of decision power in the hands of large coin-holders, the BIS said.

Proof-of-work, the consensus mechanism that underlies bitcoin, relies on miners—the computers validating transactions on the network—proving they have expended a certain amount of electrical energy.

In proof-of-stake, miners are replaced by stakers or validators—entities who hold coins and who seek to maximise the value of their stakes.

Front-running in DeFi

The Basel-based supervisory body said that automated market-making protocols in DeFi are particularly vulnerable to manipulation.

This is because large validators have an incentive to ‘front-run’ client trades, since they have the ability to order transactions in the next cryptocurrency block to benefit themselves.

“In the past several years, the exploitation of [cryptocurrency miners’] transaction ordering power has become a major issue,” Angela Walch, professor of law at St. Mary’s University, Texas, told a US congressional committee in July.

Walch is a recent interviewee on the New Money Review podcast, where she talks at length about the governance challenges facing cryptocurrency networks.

DeFi fraud risk

The experimental nature of DeFi also means that the area has attracted some of the most ingenious fraudsters.

Cryptocurrency research firm Elliptic said in mid-November that losses from DeFi scams have reached $10.5bn this year, up 600 percent since 2020.

Last month Binance’s CEO, Changpeng Zhao, said the exchange was not responsible for any scams occurring on its DeFi platform, BSC.

On Friday, cryptocurrency lending platform Celsius Network said it had lost over $50m in another DeFi hack, this time affecting an automated lending protocol called BadgerDAO.

US regulators have recently sought to crack down on cryptocurrency lenders such as Celsius, BlockFi and Nexo, arguing that their promise of yield on pledged cryptocurrency constitutes an investment contract.

“Possible fire sales by a stablecoin could [have] a severe impact on the broader financial system”

Systemic risks from DeFi are rising

In its quarterly report, the BIS said that contagion risks from DeFi had so far been limited, but are rising.

“Due to the largely self-contained nature of DeFi, episodes of rapid deleveraging have thus far had little effect outside crypto markets,” the BIS said.

However, this could change, the BIS went on, if a panic caused by a stablecoin ‘breaking the buck’ spread outside the cryptocurrency markets.

“Possible fire sales by a stablecoin of its reserve assets could generate funding shocks for corporates and banks, with a potentially severe impact on the broader financial system and the economy,” the BIS warned.

While banks’ investments in DeFi are limited, the BIS said, on the liability side, some banks could receive funding from DeFi, since stablecoins might hold their certificates of deposit or commercial paper.

As a result, runs on stablecoins, like a run on money market funds, could generate a funding shock for banks, the BIS said.

The BIS also cautioned that asset managers could act as a conduit for DeFi risks, especially if leverage was involved.

“Traditional non-bank investors are taking a growing interest in DeFi, as well as in the broader crypto markets,” the BIS said.

“At present these investors include primarily family offices and hedge funds, which often receive credit from major dealer banks through prime brokerage.”

In July, a former Wall Street technologist, Alexis Goldstein, warned that hedge funds’ rapidly increasing presence in the cryptocurrency markets is a blind spot for regulators and that extreme volatility in cryptocurrency could soon spread to other financial markets.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content from New Money Review

Fed says stablecoin risks are growing

A 400-year-old stablecoin (and why it failed)