Public infrastructures such as government identity schemes and payment systems can help address the risk of a big tech takeover of the digital economy, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has said in a new working paper.

In the paper, entitled “Platform-based business models and financial inclusion,” economists Karen Croxson, Jon Frost, Leonardo Gambacorta and Tommaso Valletti highlight the growing power of digital platforms like Google, Facebook (Meta), Amazon, Alibaba and Tencent.

These platforms, and similar ones run by financial technology (fintech) firms, have the ability to lower the costs of financial services and aid financial inclusion, say the authors.

Using digital technologies, platforms may lower search frictions and make verification and tracking less costly, they go on.

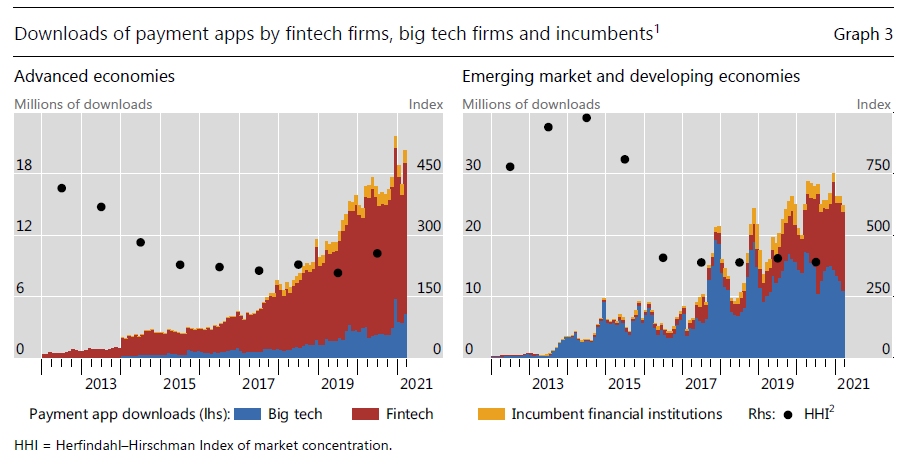

Mobile financial services platforms have exploded in popularity in recent years, say Croxson, Frost, Gambacorta and Valletti, especially in emerging economies.

For example, in China, digital platforms have enabled dramatic bounds in financial inclusion, offering low-cost payments, credit, insurance and savings products to hundreds of millions of users, leveraging their parent groups’ activities in e-commerce and social media.

In sub-Saharan Africa, mobile phone-based money platforms have played a crucial role in increasing access to low-cost payments and other financial services: as of 2019, a full 79 percent of adults in Kenya had a mobile money account.

And in India, the combination of a government digital ID infrastructure and private payment platforms have increased access to transaction accounts from 10 percent in 2008 to over 80 percent of Indian adults today.

“Big tech firms have the potential to become dominant through the data-network activities (DNA) feedback loop”

But at the same time the digital platforms’ positive returns to scale—network effects—can easily give rise to digital monopolies and oligopolies, making them near-impossible to dislodge, Croxson, Frost, Gambacorta and Valletti say.

“Big tech firms have the potential to become dominant through the advantages afforded by the so-called data-network activities (DNA) feedback loop, raising competition concerns,” they say.

And the platforms’ reach may place them outside the scope of traditional financial services regulation, they go on.

“The heavy use of personal data raises important data privacy issues. Because platform-based business models differ from traditional modes of offering financial services and the rules that govern these, there is the potential for regulatory arbitrage.”

In the paper, Croxson, Frost, Gambacorta and Valletti argue that new public infrastructures, such as digital identity, retail fast payment systems and central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), together with competition rules and requirements for data portability, offer the most promising way to control tech platforms’ power.

the cost of opening a new payments account in India has fallen from $15 to 7 cents

They cite the Indian digital ID system as an example of how private sector platform services can be built on top of a public sector infrastructure.

In 2016, India’s government introduced a country-wide national identity scheme, called ‘Aadhaar’ (Hindi for ‘foundation’).

Aadhaar is a unique biometric ID given to each Indian individual. India’s 1.3 billion citizens must have it to access social benefits such as healthcare. More than 90 percent of the adult population is now enrolled in the programme.

“[India’s] Aadhaar digital ID infrastructure, the Uniform Payments Interface for payments and the further architectures for data sharing and consent–collectively referred to as the ‘India Stack’—have been particularly helpful in allowing large digital platform providers to compete on an equal footing with banks and other non-bank payment services providers,” say Croxson, Frost, Gambacorta and Valletti.

This public/private architecture has harnessed the low costs and network effects of platforms while preventing concentration of data and market power, the authors argue, citing evidence that the cost of opening a new payments account in India has fallen from $15 to 7 cents.

However, to achieve success when managing big tech firms’ growing footprint in finance, governments will need to move away from a silo-based approach to regulation, say Croxson, Frost, Gambacorta and Valletti.

Central banks and financial regulators will need to work with competition and data protection authorities, as well as coordinating with policy experts in telecommunications and tax policy, they say.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content from New Money Review