How to create a debit card using stolen ID details

Tim Yunusov, our intrepid hacking correspondent, shows how easy it is to circumvent technology firms’ ID checks–and to spend money that isn’t yours.

In this article I’ll show how alarmingly easy it is to open a new debit card account using a stolen identity and to spend money on that card (I am not recommending that anyone take this step, but it’s elementary and cheap—around £12—to obtain such a fake ID).

Before I do so, let’s remind ourselves of the checks that are supposed to stop such things happening.

If you opened a bank account after 2017, you likely did so without visiting a bank branch at all. The so-called remote onboarding of clients is now standard at both traditional and internet-only banks.

You, as a new client, must pass electronic know-your-customer (e-KYC) checks. Usually, the firm you’re opening an account with—a bank, e-money or other financial technology (fintech) firm—doesn’t review your application itself. Instead, it outsources the KYC to another service provider.

It’s elementary and cheap—around £12—to obtain a fake ID

The KYC process consists of a proof of identity and a proof of address. Although the requirements may vary from provider to provider, most will ask you to send photos of your ID and bills and to take a picture of yourself. Some providers require a video recording of an individual and some live operations with the ID during the recording to prove its genuineness.

All these steps appear to show the robustness of the e-KYC process. However, earlier this year I showed in a New Money Review article that it’s relatively easy to bypass these checks, creating all kinds of crime risks: money laundering, sanctions evasion and terrorism sponsorship.

Then another question came to mind. What if even these steps are redundant? What if there are ways to open an account without any formal KYC verification?

In this article I’ll show how easy it was for me to enrol a wallet and to create a virtual debit card using only publicly available data.

We will use a Samsung Pay mobile wallet for this purpose, and there’s a specific reason for doing so. Compared to other mobile wallets like Google Pay and Apple Pay, Samsung Pay is not very popular in the UK and EU, with fewer than ten banks supporting it in the UK.

If you tried adding your existing debit card to Samsung Pay, you would often get the notification, “Sorry, your bank is not supported yet,” and there was nothing you could do. So a couple of years ago, Samsung partnered with fintech firm Curve to solve the problem.

I’ll show how easy it was for me to enrol a wallet and to create a virtual debit card using only publicly available data

Curve allows customers to consolidate multiple payment cards into a single card. A ‘default’ card, chosen in the app, will be charged when you pay with a Curve card. What if you don’t have money in the default account? You can select a rescue card that will be automatically charged next (‘anti-embarrassing mode’). Have you set the wrong ‘default’ card? Curve can reverse your transaction and take money from the correct account within three months. Superb!

So when trying to add a card that Samsung Pay doesn’t support, a phone would now enrol a Curve account and automatically add your card to Curve. And voila! Samsung Pay now supports your card via the ‘proxy’ Curve solution.

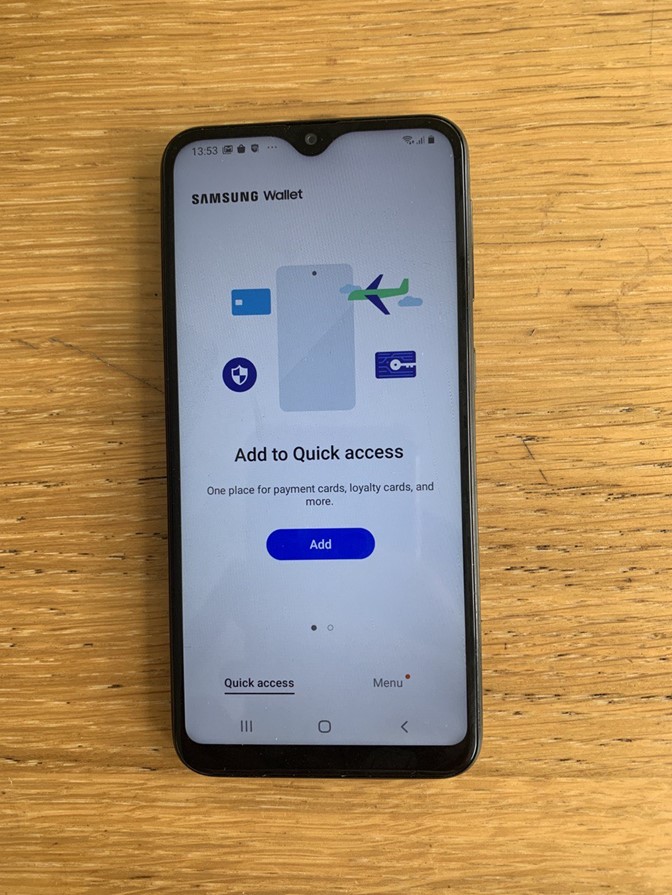

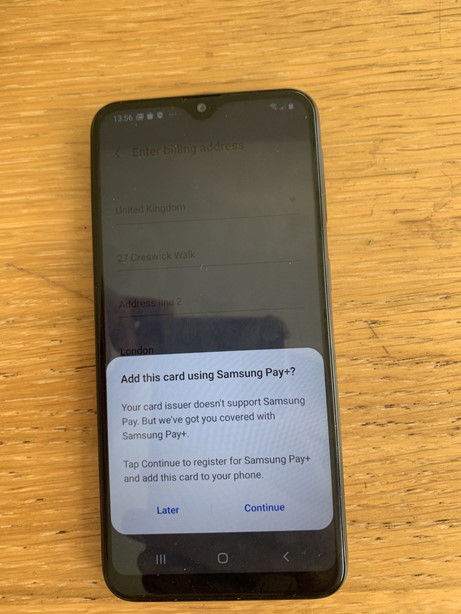

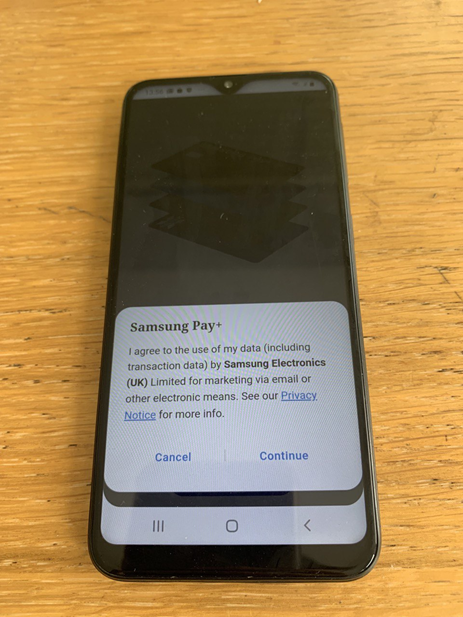

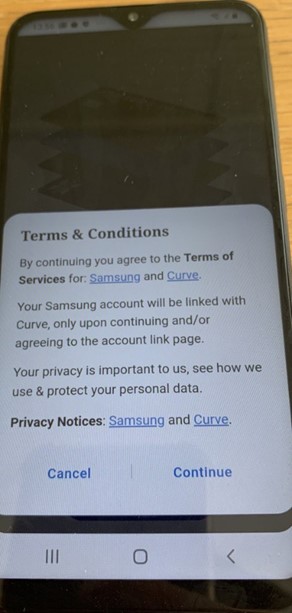

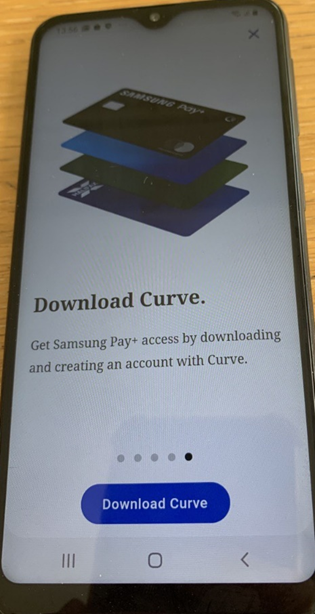

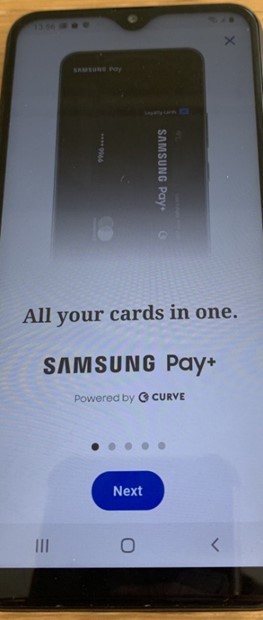

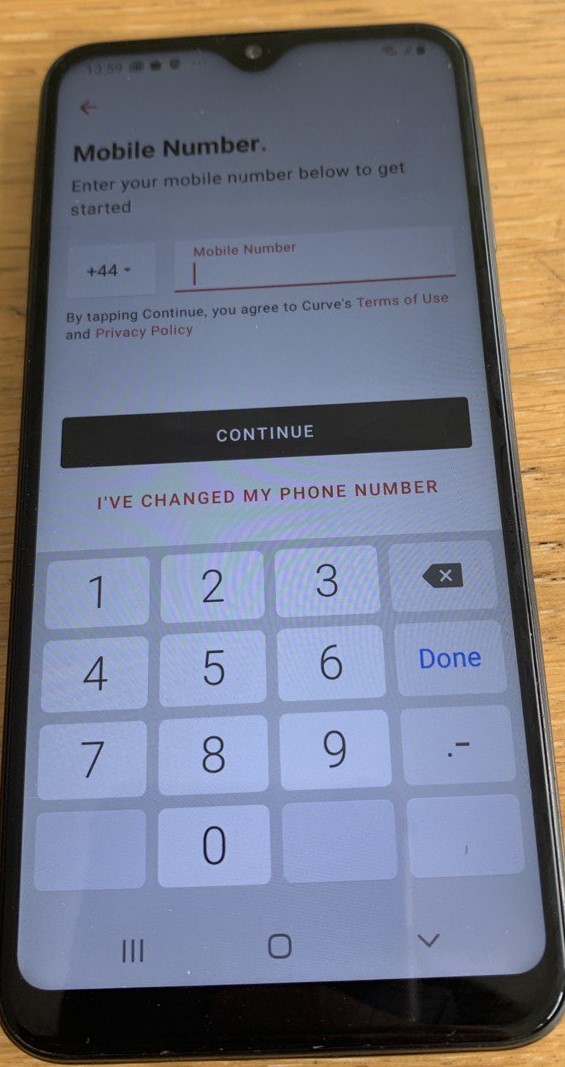

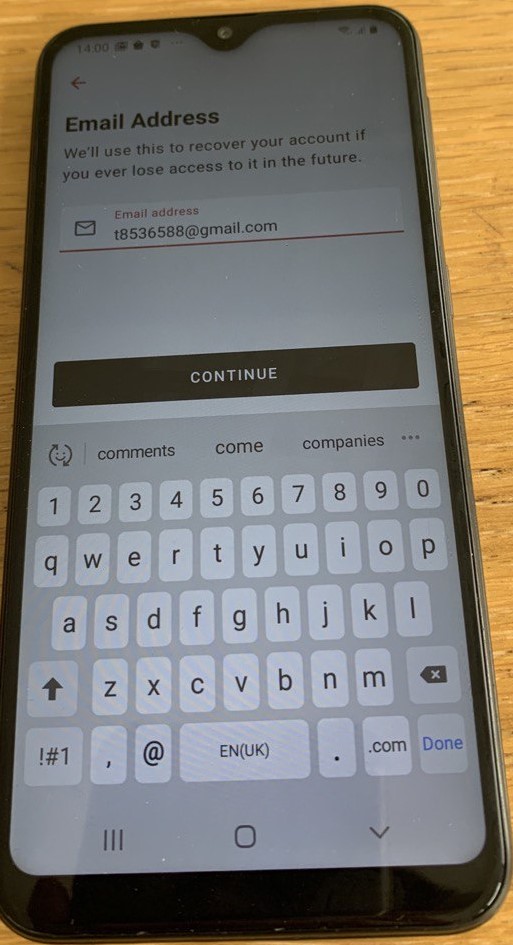

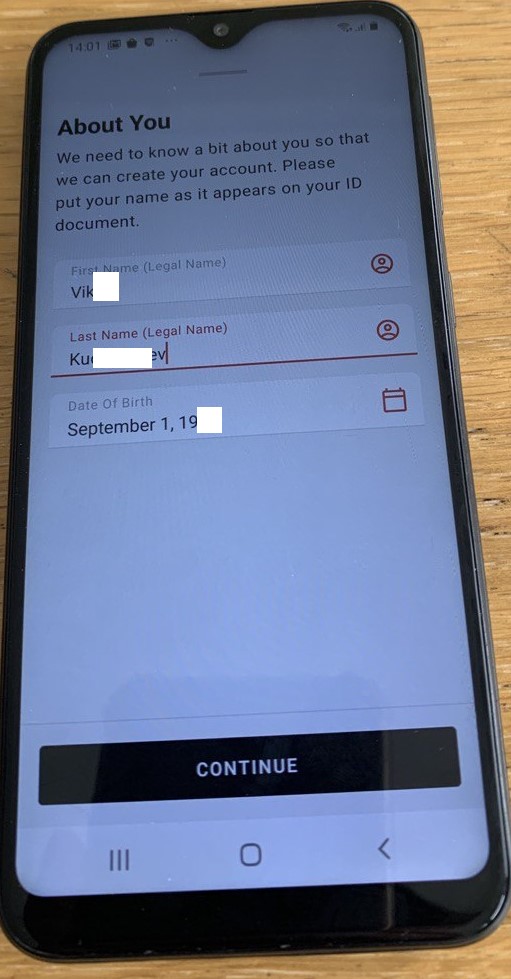

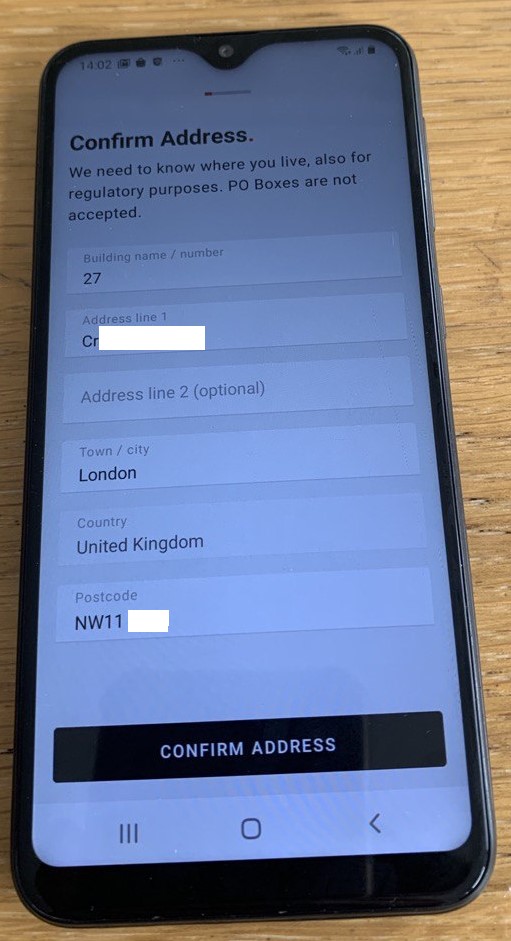

I’ve illustrated the account opening process for Samsung and Curve in the screenshots below.

Step 1.

Add the Samsung Pay app (now called ‘wallet’)

Step 2.

Adding a Revolut debit card (Samsung Pay tells us Revolut doesn’t support the app, so it prompts the user to download Curve–which then does allow us to add Revolut).

Step 3.

We use a fresh mobile number and an email to register. Then we use the stolen identity details: someone’s first and last name, their date of birth and their home address.

Where could anyone get this fake ID information from? I don’t want to point the finger, but criminals can get the ID components from different public databases without too much trouble.

And that’s it! We have now got a virtual Revolut card with which to pay online, as well as a mobile wallet we can use to pay in stores!

But what happened to the proof of address and the proof of identity checks? Curve uses a service provider called Onfido for these checks, but when it partnered with Samsung, the two firms came up with a shortcut named ‘progressive’ or ‘tiered’ KYC.

criminals can get the ID components from different public databases without too much trouble

Tiered KYC allows Curve to carry out only limited checks until you spend your first £100. Once you pass that limit, Onfido will carry out a formal proof of your address and identity.

I discovered another vulnerability at Curve: I found I could add stolen cards by knowing the long card number and expiry date. A further vulnerability allowed me to bypass the ‘3D-Secure’ verification step when adding the card.

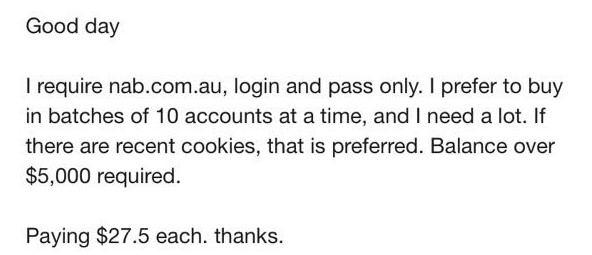

To bypass this check, criminals would need live access to a stolen card’s transaction statements. But these are pretty standard pieces of information, sold across dark web markets:

Dark web ad requesting bulk stolen bank log-in details

In summary, it was possible to add a stolen card to the Curve account without the card’s three-digit (CVV2) code or the cardholder’s 3D-Secure code.

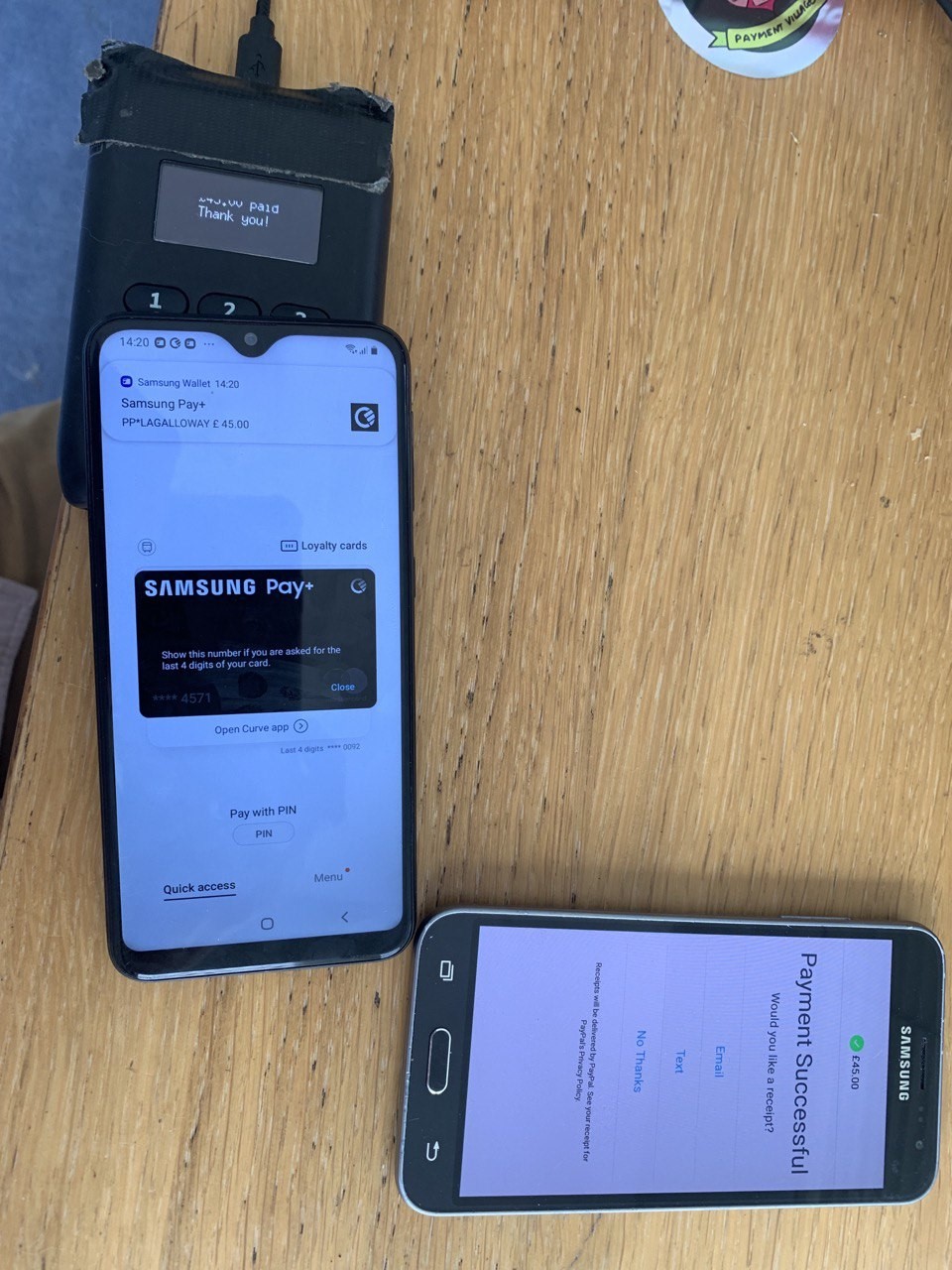

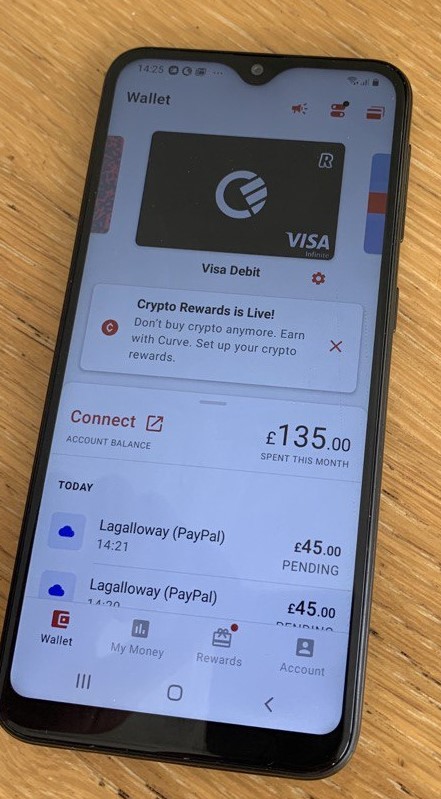

Finally, I knew that Curve has a blindspot around simple logic and mathematics. So I assumed that I would be able to spend more than £100 without any verification. Indeed, I found I could make three payments, totalling £135, before the account was suspended.

Exceeding Curve’s £100 limit before formal KYC is triggered

But even the £100 limit is an illusion!

Using the same phone, I registered three different accounts with information from people who kindly provided their names to me for testing purposes. I could do this over and over again on the same device, without raising any suspicions.

nothing stops criminals from opening hundreds of accounts and moving more than £100 from each

So nothing stops criminals from opening hundreds of accounts and moving more than £100 from each using stolen cards.

To reiterate, how could criminals with Samsung Pay use stolen identities and cards?

- Buy a device that supports Samsung Pay.

- Create a fresh digital account (phone number and email).

- Download the Curve app and create an account using information from a stolen identity (first and last name, date of birth, address).

- Add stolen cards to Curve by knowing only the long card number and the expiry date and having real-time access to bank statements.

- Make in-store or online payments within the £100-£135 range.

- Resell purchased goods or apply a known money movements scheme.

- Repeat steps 2-6 using the same device but different identities and phone numbers.

You may now be in a cold sweat, having decided you’re going to return to using cash for payments. So let me finish on a note of relative reassurance.

Recently, Curve fixed some of the most serious issues I highlighted, and now it’s much harder (but not impossible) to enrol stolen cards into the app. But there are other threats that unlimited access to virtual cards could pose. We will highlight those in our next article!

Finally, what could Samsung and Curve have done better?

The advantages offered by new technology like mobile wallets and apps like Curve sometimes open doors for criminals. It’s important to counteract these by implementing additional checks.

There’s nothing bad in the tiered KYC approach itself, unless criminals can start adding stolen cards in bulk or applying money movement schemes that are possible because of the specific features of the fintech design. So the answer is to raise risk thresholds for these features and to fix your enrolment process to deter criminals.

Tim Yunusov is a senior security researcher with application security and offensive research experience since 2009.

He specialises in the security assessment of payment systems (online-, core- and mobile banking, ATM, POS, credit card processing). He is the author of security research and security articles and one of the organisers of Payment Village.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content from New Money Review

Kleptocratic money flows may kill democracy

The battle over financial privacy

Companies and partnerships launder most dirty money

Fake IDs blow holes in Russia sanctions