International banking business has shrunk since the financial crisis of 2008, reversing a six-decade trend of increasing globalisation, according to new research from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

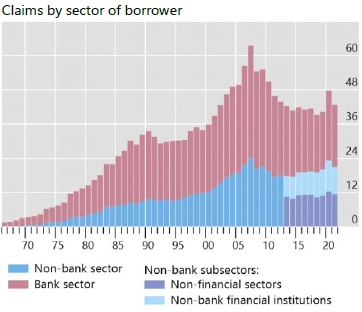

In its September 2021 quarterly review, the BIS says that banks’ outstanding international claims amounted to less than 2 percent of world GDP in 1963, but grew to 60 percent in 2007 before retreating to near 40 percent in early 2021.

The BIS defines international banking as cross-border business in any currency and local business in foreign currencies.

According to the BIS, regulatory arbitrage, financial innovation and financial liberalisation were key drivers of the growth in international banking during the decades preceding the financial crisis.

For example, the eurodollar market—the largely London-based market for wholesale dollar deposits and loans—grew rapidly from the 1950s onwards. It offered more competitive rates to both depositors and borrowers than the domestic US market, which was constrained by an interest rate ceiling on dollar deposits until 1970.

The development of new financial products, such as derivatives, whose value soared after the 1980s, also altered the way that banks managed risks in their international portfolios, the BIS said in its report.

“The transition of the broader international financial system from a tightly managed one with extensive exchange controls and capital account restrictions to today’s market-driven, integrated system was both a cause and a symptom of international banking’s growth.”

However, the runaway growth of cross-border private credit after the second world war also had its downsides. It left the global financial system prone to instability, the BIS said.

“Cross-border lending enabled the credit booms at the heart of several international financial crises, notably the Latin American debt crisis in the early 1980s, the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s and the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007–09. Ahead of each crisis, competition among banks for market share contributed to surges in international credit,” the BIS said.

Since 2008, the BIS said in its quarterly report, there has been a marked shift in banks’ global risk appetite.

Losses during the Great Financial Crisis, and regulatory reforms in its wake, have constrained banks’ expansion, making way for non-bank financial institutions, such as asset managers, to step in as major international creditors.

The growing role of non-banks in the global credit system brings its own challenges, according to the BIS.

“While today banks are perceived as a source of strength for the financial system, past episodes of turmoil demonstrate how the troubles of non-bank financial institutions can spill over to banks in unforeseen ways.”

The BIS said that the G20 Financial Stability Board and other regulators are pushing for more transparency about non-bank finance, including revised regulation and liquidity backstops.

It pointed out that non-banks’ short-term dollar funding needs during the 2008 crisis and the 2020 coronavirus market slump had been met by coordinated government action, specifically via swap lines between central banks.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content from New Money Review

BIS warns on rise of shadow payments

The cross-border payment challenge