Stablecoins—digital money backed by assets of stable value—are in vogue. But for a stablecoin to function, its users have to trust in its backing. And history is full of examples when the vault containing a stablecoin’s assets ended up short.

The Bank of Amsterdam, a proto-stablecoin set up in 1609, worked well for over 170 years. Its money was backed by silver and gold coins held in the Bank’s vaults.

As the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) describes in a recent paper, the Bank of Amsterdam’s structure and governance were designed to ensure it kept its promises.

The Bank’s charter forbade lending: it could only issue money up to the amount of gold and silver it held. If depositors withdrew money, it had to shrink the money supply. On one occasion, it did exactly that, even at the cost of devastating the local economy.

When England, France and two German armies attacked Holland in 1672, there was an outflow of bullion from the Bank’s vaults. The money supply dropped by 75 percent and the Bank balance sheet shrank accordingly. The country suffered a sharp fall in economic output and house prices fell by half.

But the Bank kept functioning throughout the crisis and even opened its vaults to prove it held the right amount of precious metal in reserve, helping restore confidence.

The Bank of Amsterdam was a public-private concern. It was fully owned by the city of Amsterdam, but its day-to-day functions were overseen by three commissioners. These were usually merchants or members of the city council. To prevent nepotism or insider dealing, they were appointed for only a year at a time.

But even these safeguards ended up being insufficient, says the BIS.

By the mid-18th century, the Bank of Amsterdam had started lending to corporate clients, notably the Dutch East India company, in contravention of its charter and without disclosing the lending.

Initially, the lending was small in proportion to the Bank’s overall balance sheet and it did not impact the financial strength of the Bank or the confidence in its money.

But by the end of the century, the Bank became progressively looser in its lending policy, sowing the seeds for its eventual failure. Geopolitics, domestic tensions and a loosening of governance standards all played a part in the decline.

In the late 1770s, another war with the English led to renewed economic pressures. This time, rather than shrinking its balance sheet, the Bank lent much more, in a sustained and non-transparent way.

And by now, an excessively cosy relationship between the Amsterdam municipal authorities and the Bank’s commissioners had made the latter overlook the breaches of the Bank’s charter.

The commissioners had become younger too—33 years old on average, by this time, compared to 46 when the Bank was founded—making them more susceptible to pressure.

By the late 1780s, loans to the Dutch East India company, the Amsterdam Town Treasury and the Loan Chamber made up 75 percent of the Bank’s balance sheet, with only a quarter in bullion.

In 1795, after French revolutionary armies invaded the Netherlands by French revolutionary armies, the true extent of the Bank’s insolvency came to light. It lived on in a weakened state for a little longer, then closed in 1820.

Can the modern-day providers of stablecoins resist the pressures that eventually brought down the Bank of Amsterdam?

The BIS takes the view that privately run stablecoins are inherently unstable.

“Maintaining the value of the stablecoin through 100 percent backing would be in the interests of the holders of the stablecoin. But the manager may face incentives to decrease the backing ratio by responding to demand for credit, since this will increase profits,” it says.

To reassure its users, the managers of the second-largest private stablecoin, Circle, with $7bn in issue, publishes a monthly attestation report of its reserves, given by accountancy firm Grant Thornton.

But the largest stablecoin issuer, Tether, has still not exposed its reserves to an external auditor.

In January 2018, Tether ended an attempt by accountancy firm Friedman LLP to audit its reserves, saying that “the excruciatingly detailed procedures Friedman was undertaking for the relatively simple balance sheet of Tether” meant it had become clear that an audit “would be unattainable in a reasonable time frame”.

In April 2019, the New York attorney general sued the owners of Tether and its affiliate, cryptocurrency exchange Bitfinex, alleging that the companies had conspired to hide a $900m loan from Tether to Bitfinex, taken out of tether token holders’ funds.

The loan had caused Tether’s asset backing to fall, said the attorney general, with only 74 percent of the tethers in issue backed by dollars held in bank accounts.

On 5 February, Tether issued a statement saying the remaining $550m of the loan owed by Bitfinex had now been repaid.

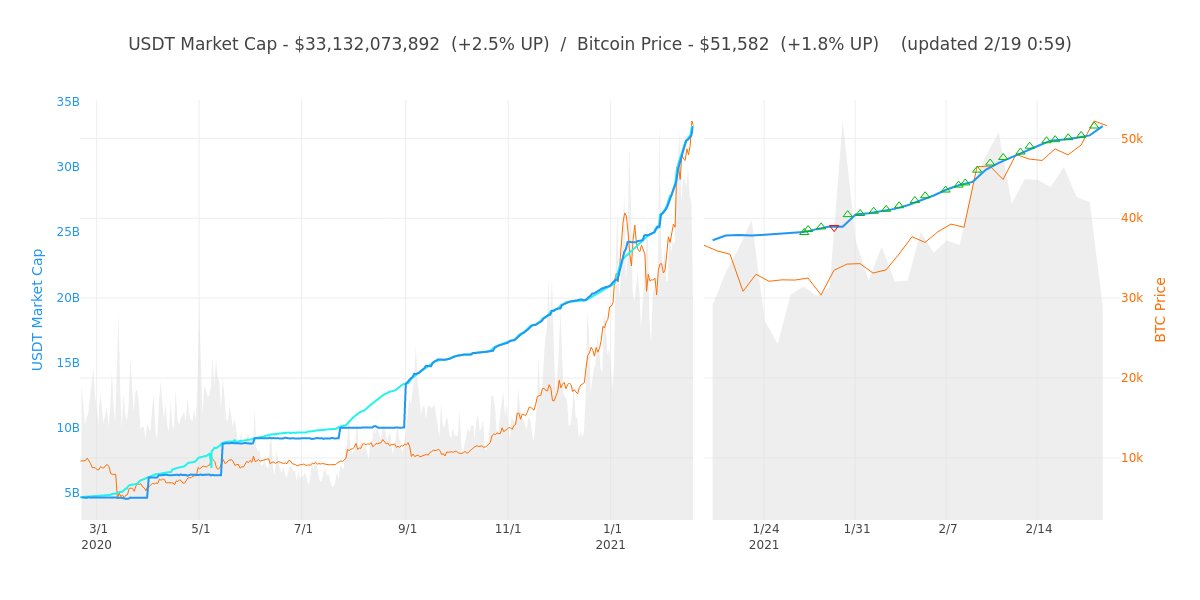

In recent weeks, the value of tethers in issue has ballooned to over $33bn, with the pace of issuance picking up in tandem with the bitcoin bull market.

Tethers in issue (left), bitcoin price with green triangles marking tether issuance (right)

But the stablecoin issuer’s own assertions that it has restored full backing to its tokens have done little to quell the voices of the sceptics.

“Tether’s days are counted. Whether by natural implosion or as a result of regulatory action, the stablecoin funding a wide array of offshore crypto activity will go the way of the dodo,” one blogger, Trolly McTrollface, wrote this week.

For another cryptocurrency critic, the recent accelerating issuance of tethers is a sure sign of a pyramid scheme approaching its endgame.

“We also know they are really issuing, literally, at an exponential rate, new tethers,” Nouriel Roubini said on Coindesk TV last week.

“In the last year alone, something like 25 billion. And in the last few weeks, a billion per week. So it looks like they are getting desperate, and it is a typical ponzi scheme, in which you maintain the value of something by issuing more of it and more of it.”

With Tether still embroiled in its New York lawsuit and facing enquiries from the US Department of Justice and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, it’s surely only a matter of time before the stablecoin issuer reaches its Bank of Amsterdam moment and has to open its vaults.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content on New Money Review

Where’s my money? Wirecard and tether

Central banks brace for stablecoin explosion