Doubts remain about the leading cryptocurrency’s long-term viability.

Bitcoin miners—the computers securing the network and keeping a record of transactions—rely on two sources of income: the block reward and the transaction fees from those trading in bitcoin.

As the block reward is designed to decrease over time—it was cut from 12.5 to 6.25 bitcoins per block on May 11 last year, and will halve again in 2024—transaction fees are destined to become an increasingly important part of miners’ income.

A bitcoin block occurs on average every ten minutes, meaning that at present miners earn a collective 900 coins a day from the block subsidy, worth around $47m at current market prices.

But for the network to survive after the block reward disappears next century, transaction fees will have to take over completely, something that bitcoin’s creator recognised at the start.

“The incentive can transition entirely to transaction fees”

“The [miners’] incentive can also be funded with transaction fees… Once a predetermined number of coins have entered circulation, the incentive can transition entirely to transaction fees and be completely inflation-free,” Satoshi Nakamoto wrote in the bitcoin white paper.

Since March last year, bitcoin has embarked on a major bull market, with the price of a coin rising from $3,913 on March 9, 2020 to a new record of $52,779, set yesterday.

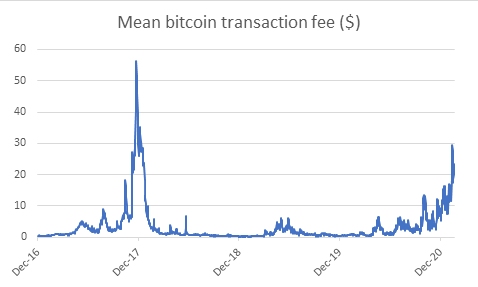

In parallel, the cost of a bitcoin transaction has risen to $20-30, a big jump compared to a year ago, but still short of the $50-60 transaction fee peak reached in December 2017.

Technical changes made to the bitcoin protocol in 2018 helped reduce the amount of block space needed to process transactions, prompting a relative decline in fees after the 2017 spike.

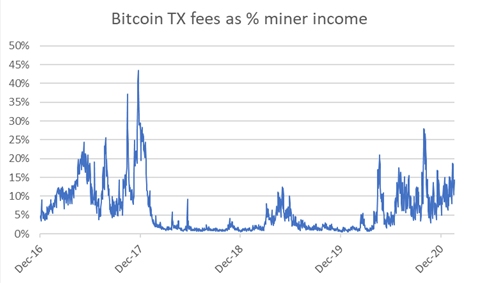

As a percentage of overall miner income, transaction fees have also been on the rise in recent months. But even at the latest, $20-per-transaction rate, they still only make up around 15 percent of the total miner reward, with the remaining 85 percent coming from the block subsidy.

Charts from Coinmetrics

Amidst the short-term focus of a speculative frenzy, a few analysts are looking longer-term at bitcoin’s incentive model—and they see problems ahead.

In 2016, four computer scientists at Princeton University published a paper on the instability of bitcoin without the block reward.

“With only transaction fees, the variance of the block reward is very high”

“With only transaction fees, the variance of the block reward is very high…, and it becomes attractive to fork a ‘wealthy’ block to ‘steal’ the rewards therein. We show that this results in an equilibrium with undesirable properties for bitcoin’s security and performance,” the academics wrote.

“We see the block reward as integral to the stability of the mining game,” they went on, providing evidence that a transaction fee-only regime would be much more unstable than bitcoin’s current set-up.

In a blog written last year, an anonymous German bitcoin researcher called 0xb10c explained how miners could attempt to steal profitable transactions from each other by reorganising (intentionally forking) the blockchain, something that becomes economically more viable once the block subsidy disappears.

“Fee-sniping is currently not used by miners but could cause chain reorganisations in the future,” 0xb10c said.

“If a recent block contains a transaction paying a relatively high fee, then it could be profitable for a larger miner to attempt to reorg this block. By mining a replacement block, the sniping miner can pay out the transaction fees to himself, as long as his block ends up in the strong-chain,” he/she went on.

“The fee-sniping miner is not limited to pick the same transactions as the miner he is trying to snipe. He would want to maximize his profitability by picking the highest feerate transactions from both the to-be-replaced-block and the recently broadcast transactions currently residing in the mempool. The more hashrate a fee-sniping miner controls, the higher is the probability that he will win the block-race. Miners have the risk of losing such a block-race, leaving them without reward.”

0xb10c said that using a time-lock for bitcoin transactions could help mitigate the risk of future disruptive forks of the blockchain.

Since 2015, it has been possible to use such a lock to restrict the spending of bitcoins until a specified future time or block height (‘height’ is the numbering convention for bitcoin blocks—each block is one higher than the previous one).

According to the bitcoin wiki, in 2019 around 20 percent of all bitcoin transactions included a time-lock, intended to make any future potential fee-sniping less profitable.

However, according to Miles Carlsten, one of the authors of the 2016 Princeton paper, this is insufficient to remove concerns about bitcoin’s future viability in the absence of a block reward.

“The most important reason why time-locking transactions doesn’t solve the [fee-sniping] problem is that no centralised authority exists to enforce that everyone uses these locks,” he told New Money Review.

“As long as some transaction fees are attached to transactions that do not have time-locks, miners can explicitly pick these fees to be the ones to use as the ‘bribes’,” he said.

“Beyond these time-locks, I have heard of no other rebuttal to this type of [selfish miner] attack and still believe that there’s a challenge for bitcoin to overcome when it comes to transaction fees replacing the block reward (and the time-dependence this brings to the overall reward for mining a block),” said Carlsten.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content on New Money Review

Taking the difficulty out of bitcoin