When the UK imposed its first coronavirus lockdown on 16 March, some consumers found they couldn’t get their money back for services they had paid for but were no longer able to use: the seller refused to offer a refund.

One of the worst offenders was Hoseasons, which operates holiday accommodation in the UK. Its customers were told to rebook or accept a voucher rather than being offered their cash back. Hoseasons is owned by private equity firm Platinum Equity.

“The way they have treated customers during this pandemic is shocking,” one client said on Trustpilot in April.

“The way they have treated customers during this pandemic is shocking”

“We didn’t choose to cancel, they cancelled, but we are still not entitled to a refund. All you get is a pathetic voucher and a more expensive holiday if you book it for later in the year. Hoseasons’ management are just greedy!” the client complained.

The travel firm was forced to reverse its stance when the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), which looks after consumers’ rights, started an investigation into the company.

By June Hoseasons had agreed to offer full refunds to customers who had booked holiday homes but could not stay in them post-lockdown.

The firm now makes a virtue of its willingness to repay consumers: on its website it advertises a ‘full refund if we have to cancel your holiday’.

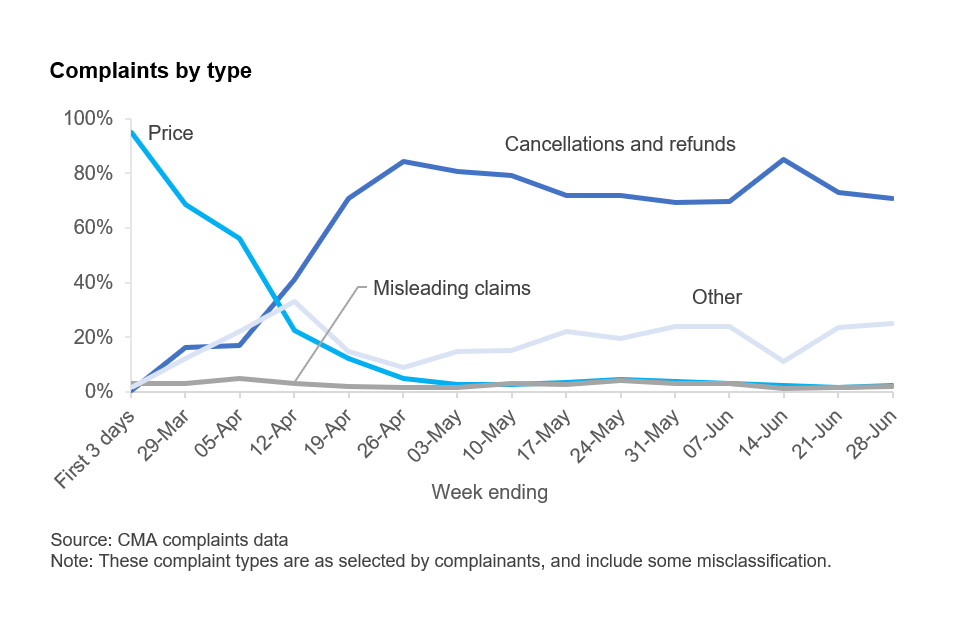

But the case illustrates a wider problem. According to the CMA, the number of complaints it receives relating to cancellations and refunds has shot up since the beginning of the pandemic, while complaints over pricing and misleading claims have dropped.

The regulator says the worst culprits in the no-refund stakes were large companies supplying services to do with travel, holidays and accommodation.

The fallback is chargeback

Fortunately, for UK consumers stuck in a similar situation, there are other ways to get your money back.

The most reliable route—but which only applies if a customer has spent between £100 and £30,000 and only by credit card—is to claim directly from the credit card provider, who bears joint responsibility with the retailer or trader for any breach of contract or misrepresentation.

For those paying by debit card or anyone paying a small amount by credit card, the fallback is to rely on a less legally secure option—making a chargeback.

The ultimate say over whether clients get their money back rests with the bank

Chargebacks are agreed between financial institutions and card schemes, such as American Express, Mastercard and Visa. But the ultimate say over whether clients get their money back rests with the bank issuing the card.

The UK’s Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS), which has no enforcement powers, has said it expects banks to try a chargeback if there’s a reasonable prospect of success.

But Which magazine reported in April that banks had been treating very similar chargeback cases differently.

According to Which, some banks had helped refund consumer cash when businesses had only offered credit notes or vouchers. But other banks in the same situation had rejected chargebacks on the basis that the businesses had tried to offer a suitable alternative.

Which asked a number of card-issuing UK banks to explain their chargeback policy but most were vague in response.

“Every chargeback and dispute is different, and each case will need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis with the customer to work out the best solution,” Metro Bank told Which at the time.

“This is because the terms and conditions of the contract between the customer and the merchant will vary so a one-size-fits-all policy doesn’t work.”

For its part, the CMA says that in most cases it would expect a business to offer a full refund to clients if it had cancelled a contract without providing any of the promised goods or services, if no service is provided as a result of lockdown-related restrictions, or if a consumer cancels a contract because of lockdown restrictions.

But the CMA’s powers only go so far: it says it has no power to force airlines to refund customers, and aggrieved consumers will have to take up their case with the UK’s Civil Aviation Authority.

Murky rights and costs

If the vagueness of chargeback rights seems a recipe for confusion, card firms and banks keep them in place because they are valued by consumers.

According to Lana Swartz, an assistant professor of media studies at the University of Virginia and a specialist in digital money and payments, chargebacks play an important role in bringing a consumer and a card company into a relationship of trust

In her book, ‘New money—how payment became social media’, Swartz compares paying with a card and paying with cash.

“The card issuer becomes a guardian of the cardholder’s financial interests”

“For those who exchanged their cash for goods or services, it was buyer beware,” she says.

By allowing cardholders to revoke payment through chargeback, the card firm extends the relationship of trust from a point in time—the moment of payment—to a period of weeks and months.

“The card issuer becomes a guardian and a steward of the cardholder’s financial interests,” says Swartz.

But the underlying risks and costs of chargeback are opaque.

According to Swartz, US card providers typically charge merchants about 1 percent of each transaction for chargeback risk, a cost that ends up being borne by consumers as it’s built into sales prices.

But card providers can levy a much higher chargeback rate–up to 4 percent—for perceived high-risk online business, such as pornography, Swartz says.

Confusingly, third-party payment processing companies—who act as intermediaries between the merchants of goods and services and banks—often prefer high-risk payments business, Swartz says, despite the likelihood of being hit by larger requests for refunds.

For these middlemen, “the ideal customer is one who is considered the riskiest—and therefore can be charged the highest prices—but who doesn’t actually generate that many chargebacks and, crucially, is not actually doing anything illegal,” Swartz says.

The higher-margin payments business generated by pornography, gambling and other adult services is risky all the same. Wirecard, the German payments firm that collapsed so spectacularly this year, specialised in it.

Paying for protection

The consumer protection promise that underlies chargebacks—and any offer of compensation for a financial transaction that goes wrong—is ultimately just a form of insurance.

According to Nilixa Devlukia, a former payments regulator and now a consultant, the terms and cost of this insurance should become more explicit.

She says this year’s consumer payments problems have highlighted the need for further transparency about refund rights following payments made with debit or credit cards.

“Given what happened during Covid—when people did or didn’t get their money back and the challenges they had—I think suddenly there is more of an interest in consumer protection,” she told New Money Review.

“People are going to think, ‘How am I paying for this and what protection is it going to give me?’”

“I wonder whether protection may become a more transparent cost. It may even be a competitive advantage for those offering it,” she said.

Sign up here for the monthly New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes