Wednesday’s dramatic Twitter hack has led to a spat between a firm of cryptocurrency investigators and a provider of bitcoin privacy software.

More than a fifth of the funds raised by the scam passed to a bitcoin mixing service called Wasabi, Elliptic, a leading blockchain forensics firm, said this weekend.

Economic crime has shifted online

According to Elliptic, which works with financial institutions, cryptocurrency exchanges, regulators and law enforcement bodies to track money flows in cryptoassets, economic crime and the trade in illicit goods have shifted online as the world has become increasingly digitised.

Use of the dark web is increasing by 50 percent year-on-year, Elliptic says, and cryptocurrencies like bitcoin have become the primary means of exchange for those preferring to transact outside the conventional financial system.

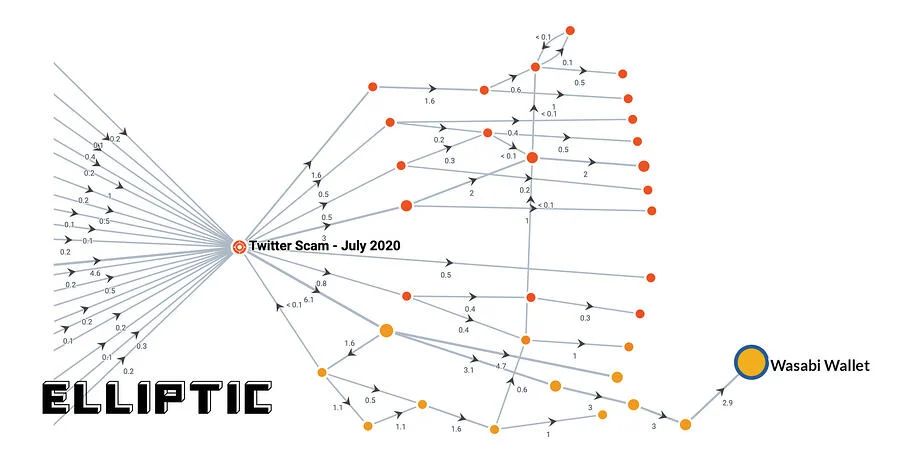

According to Elliptic, 2.89 bitcoins, accounting for 22 percent of the funds obtained by the Twitter hacker, were sent to an address that “we strongly believe to be part of a Wasabi Wallet”.

Elliptic’s infographic of the Twitter hack bitcoin

Wasabi specialises in ‘coinjoins’, which involve the mixing up of the inputs and outputs to a single bitcoin transaction so as to obscure the ownership of the coins.

By design, all past bitcoin transactions are open to public inspection.

Last month investigators at European police intelligence agency Europol said in a leaked report that coinjoin services like Wasabi were making it difficult for them to do their job of tracing criminals.

“The sheer amount of transactions and uniform output amounts typically offer too many options of where the funds could have moved,” Europol said, referring to Wasabi.

Europol said that “things are not looking good” when it comes to law enforcement investigations involving funds passing through Wasabi.

“The hackers will now be focused on how to cash out their bitcoins”

However, according to Elliptic the funds raise by the Twitter hacker are now basically useless—unable to be spent.

“The hackers will now be focused on how to cash out their bitcoins, likely through one or more crypto exchanges,” said Tom Robinson, Elliptic’s chief scientist.

“The challenge they face is when exchanges use blockchain monitoring tools such as Elliptic’s to scan the blockchain and determine the source of the funds for any bitcoin transaction they receive.”

“If our software tells them that the funds originated from the Twitter attack, they are likely to freeze the funds and notify law enforcement,” Robinson said.

Earlier today, Wasabi published a blog in which it did not deny its coinjoin wallet’s possible involvement in processing the bitcoin proceeds from the hack, but said most of the users of its platform were not criminals.

The blog was then removed, but is still available in a cached version.

“Although it is sad that there are dishonest people using our product, the truth is that for every 1 person utilising our coinjoin service for malevolent purposes, there’s another 100 people utilising it for the right reasons,” Wasabi said.

“Private companies, autocratic governments and corrupt institutions have no right to surveil you”

“We firmly believe that cryptocurrency is the currency of the future and that private companies, autocratic governments and corrupt institutions have no right to surveil you,” Wasabi said.

“Privacy is a fundamental human right and Wasabi Wallet is protecting people’s privacy,” Wasabi said.

According to Elliptic’s Tom Robinson, his company’s ability to spot the use of Wasabi for coinjoins should serve as a valuable tool for investigators.

“We have a unique capability to identify bitcoin addresses that are part of a Wasabi wallet,” Robinson told New Money Review.

“This is much more specific than identifying them as being used in coinjoin transactions. This is very important for our customers because they can use our solutions to identify any customer deposits originating from a Wasabi wallet,” Robinson said.

However, while Robinson said his firm can spot the ‘fingerprint’ of a Wasabi coinjoin on the bitcoin blockchain, he admitted that, unless users try to cash out their bitcoin at an exchange, this doesn’t necessarily make it easier to identify those moving the funds.

“It is very challenging to trace flows of funds through mixing/coinjoin services such as Wasabi,” Robinson said.

According to Moe Adham, CIO of Cypherpunk Holdings, which has purchased equity stakes in Wasabi and another mixing service, Samourai, Elliptic is overselling its investigative services.

“Identifying a non-custodial coinjoin transaction, such as those from Wasabi wallet, is trivial,” Adham told New Money Review.

“Identifying a transaction does not necessarily decrease the privacy of transaction participants. If any Elliptic customers are paying extra for this type of identification service, they may want to ask for a refund,” Adham said.

But given the prevalence of blockchain analysis companies, any bitcoin from last week Twitter hack that has passed through Wasabi seems as unsellable as the bitcoin funds that did not touch Wasabi.

With this in mind, New Money Review asked Adham if it’s also correct that Wasabi transactions do little to increase the privacy of those mixing coins.

“This is not a fair characterisation,” Adham said.

“Detecting a coinjoin transaction is pointing at a pile of apples and saying ‘these apples came from that tree’.”

“The challenge is in determining which apple came from which branch. This is correlated to the number of apples, and the number of branches. There is no way to know for certain, you can only make an informed guess with a probability.”

“The privacy enhancements from coinjoin derive from ‘blending in with the crowd’, Adham went on.

“Similar to a public protest, it is up to law enforcement, and society at large, to determine if all protestors should be punished for the actions of some,” he said.

“Transparency requires protection”

Although bitcoin was marketed by its creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, as peer-to-peer digital cash, for those wanting to stay invisible to the police, spy agencies or the taxman, bitcoin’s inherent traceability makes it completely different from physical cash.

In English law, physical currency enjoys a legal exemption preventing investigators from following it once it has been passed on.

“If a thief steals five £10 notes from your wallet, and you immediately apprehend him and can identify the specific notes, the £10 notes are still yours,” said Simon Gleeson, partner at law firm Clifford Chance.

“But if he can get to a shop and spend them before you catch him, you cannot recover them from the shopkeeper,” Gleeson said.

In its now-deleted blog, Wasabi made reference to this attribute of cash when defending its goal of increasing levels of privacy for those transacting on the blockchain.

“Bitcoin is a system that is transparent by definition, in which all information is publicly available and where every transaction is linked to past ones,” Wasabi said.

“For this reason, transparency requires protection. Would you want law enforcement knocking on your door because the $20 dollar bill you got from your local coffee shop could be linked 25 transactions ago to a bank robber or drug dealer? Within bitcoin’s blockchain, this is a reality and we’re doing our part to remedy this shortcoming.”

Sign up here for our monthly newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes