Entrepreneurs are competing in an intensifying race to design the future standards for the transmission of money.

Gauge war

The western English town of Gloucester was once the frontline of a battle over something remarkable—the width (or ‘gauge’) of a railway track.

In the 1840s Britain experienced its first stock market bubble for over a hundred years—railway mania.

Fired up by cheap finance and enabled by willing legislators—each new railway line had to be approved by an act of parliament—entrepreneurs rushed to cover the country with train tracks.

But they forgot one thing: to make sure that the individual networks they were building were compatible with each other.

Gloucester proved one of the choke points in the new system.

To the south and west of the town, trains travelled on a 7ft 1⁄4in (2,140 mm), ‘broad gauge’ track. But to the north, they ran on a much narrower, 4ft 8 1⁄2in (1,435 mm), ‘standard gauge’ track.

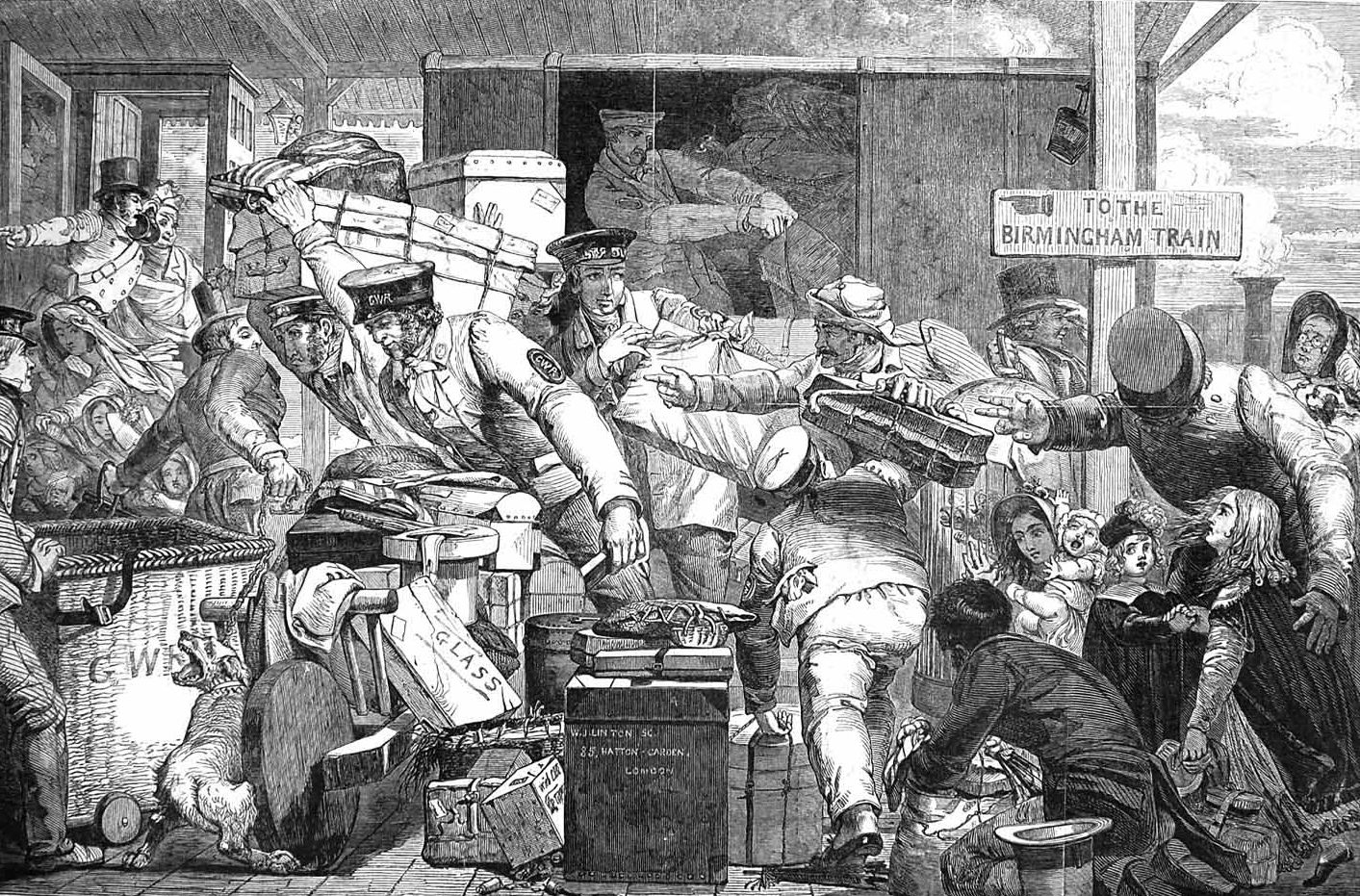

As a result, passengers and goods had to change trains in Gloucester. The result was a regular, chaotic scramble on the station platform, vividly portrayed by a cartoonist of the day.

Changing trains in Gloucester in 1846

JH Townshend, Illustrated London News

Payment rails

The so-called gauge war—the contest to set the standard for the railway’s infrastructure—was about much more than engineering. Instead, it represented a much broader struggle over commercial interests and property rights.

Now, nearly two centuries later, the gauge war has echoes in the developing set of standards for global money transmission. It’s not a coincidence that financial technologists refer to money moving across one set of ‘payment rails’ rather than another.

Rather than the width of a train track, the 21st century debate is focused on the protocols behind so-called ‘stablecoins’.

Stablecoins are digital versions of existing currencies or commodities

Stablecoins are digital versions of existing currencies or commodities, like the dollar, euro, yen or the price of gold.

Designed using the technology behind cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, they have a more modest ambition: while bitcoin often suffers wild fluctuations in its fiat currency price, stablecoins are pegged in value to that of an underlying reference asset.

The first stablecoins, such as tether, were unregulated: they were introduced to help cryptocurrency traders park their money in quasi-dollars while avoiding the intrusive anti-money-laundering checks of the conventional financial system.

But more recent stablecoin initiatives, such as Circle’s USD Coin, Paxos’s Standard Coin and Facebook’s still unlaunched Libra, have sought to bridge the gap between cryptocurrency technology and the world of regulated finance.

Unsurprisingly, global financial regulators are paying close attention to developments.

“A recent development has been the announcement by private sector actors of their intention to launch stablecoin-type arrangements for domestic and cross-border retail payments and remittances, with the potential to reach global scale (‘global stablecoins’),” the G20 Financial Stability Board wrote last year.

“This possibility could alter the current assessment that crypto-assets do not pose a material risk to financial stability. Stablecoin arrangements could potentially become a source of systemic risk. In particular, stablecoins have the potential to grow quickly as a means of payment or a store of value.”

Speaking yesterday at Messari’s ‘Mainnet’ conference, Jeremy Allaire, Circle’s CEO, spoke of a likely future explosion of stablecoin issuance.

“Taking central bank money and having it function as a digital currency over a public blockchain has only become technically feasible in recent years,” said Allaire.

“We are on the cusp of scaling techniques that are going to make this possible on a mass scale. This is like streaming videos in 2004. In the next 5-10 years we’re looking at trillions of dollars that will be tokenised [via stablecoins],” he said.

“Major financial institutions, players in the global payments ecosystem, will begin to adopt these kinds of standards. Stablecoins are going to start being used more broadly in payment and settlement, changing this into being a core part of how the internet moves value around.”

“The future of stablecoins is in global payments”

Charles Cascarilla, CEO of competing stablecoin issuer Paxos, pointed out the utility of stablecoins for a store of value like gold. Recently, the global price of gold has varied unexpectedly, depending on where settlement is taking place.

“Gold is a perfect example of an asset that can be tokenised via a stablecoin,” Cascarilla told Mainnet attendees.

“You’d like to be able to use it like a bearer instrument and move it around, without having to carry it with you, and now you can.”

“The future of stablecoins is in global payments,” said Shamir Karkal, CEO of Sila, speaking at the same event.

“Crypto is just a much better way of managing value and programming with it,” he said.

“Everyone wants interoperability and fungibility”

But if the stablecoin race is still in its early stages, said Circle’s Allaire, the ultimate prize for the winners will be the ability to establish the future technological protocols for money transfers.

“Stablecoins should be seen as open standards that people can implement,” said Allaire.

“On the internet, standards like HTTP for content, or RMTP for video, made it possible for everyone to connect and exchange information. Stablecoin standards are key, as everyone wants interoperability and fungibility.”

“That’s why we at Circle have taken the approach [with Coinbase] of creating Centre consortium, a member-driven governance standards effort, with technical contributions from third parties,” said Allaire.

“I, as a bank, might then support Circle’s stablecoin (USDC) as a [payment] rail, just as I support the [global messaging standard] SWIFT or card processing from VISA. It’s just a rail I’m plugging into.”

The standard setters

But who will the standard setters for global payment protocols be? And will a place remain for the unregulated stablecoin issuers, such as Tether?

According to Tether’s CTO, Paolo Ardoino, his company hopes to cement its position as the leading stablecoin by value.

“There is a tremendous potential for stablecoins to grow to trillions”

Tether, which is headquartered in the British Virgin Islands, is embroiled in a lawsuit in the New York state courts, where the Attorney General has provided evidence that the cryptocurrency is less than fully backed by dollar reserves.

“There is a tremendous potential for stablecoins to grow to trillions,” Ardoino told Mainnet attendees, while declining to comment on the lawsuit.

“I believe Tether has a shot to reach that level. We will do whatever it takes to make our audience and customers comfortable and we will respect the regulations wherever we try to operate.”

Sila’s CEO, Shamir Karkal, was more sceptical about Tether.

“Saying that Tether is screwed has to be one of the most uncontroversial things out there,” Karkal told a Mainnet panel. “Exactly how they are screwed is the real question.”

Meanwhile, other unregulated stablecoin initiatives are also attracting regulatory scrutiny.

“lawmakers are specifically talking about how to shut dai down”

One that’s a particular focus of attention is the decentralised ‘dai’ stablecoin, which runs on the ethereum blockchain. The dai is pegged to the dollar at a 1:1 ratio, a promise backed up by the fact that every dollar of dai is collateralised by at least $1.50 of ethereum’s native cryptocurrency, ether.

However, even this level of collateral backing proved insufficient during the sharp March sell-off in cryptocurrencies, forcing a bailout of the system by its participants.

According to Circle’s Jeremy Allaire, some regulators have been seeking to stamp out dai.

“I’ve been in rooms with lawmakers who are specifically talking about how to shut it down,” said Allaire.

“I think dai is a critical innovation that needs to survive for financial inclusion on the open internet to continue to thrive,” he continued.

Geopolitics also feature large in discussions over future payment protocols.

China’s new digital currency plans appear designed to promote the country’s technical standards across regions of the world that have signed up to the Belt-and-Road infrastructure initiative, a major development programme involving nearly 70 countries.

A messy compromise?

In the end, the stablecoin standard-setting race may end in a messy compromise, just like Britain’s nineteenth century gauge war.

In 1846, the UK Parliament mandated standard gauge for all new railway construction, but with exceptions in the southwest of England and certain lines in Wales—allowing the broad-gauge track to the south-west of Gloucester, which had powerful backers, to continue to operate.

Confusingly, new broad-gauge lines were also still legal if an act of parliament permitted an exception. As many members of the UK parliament were also speculators in railway shares, the loopholes in the new rules prompted accusations of double standards and insider dealing.

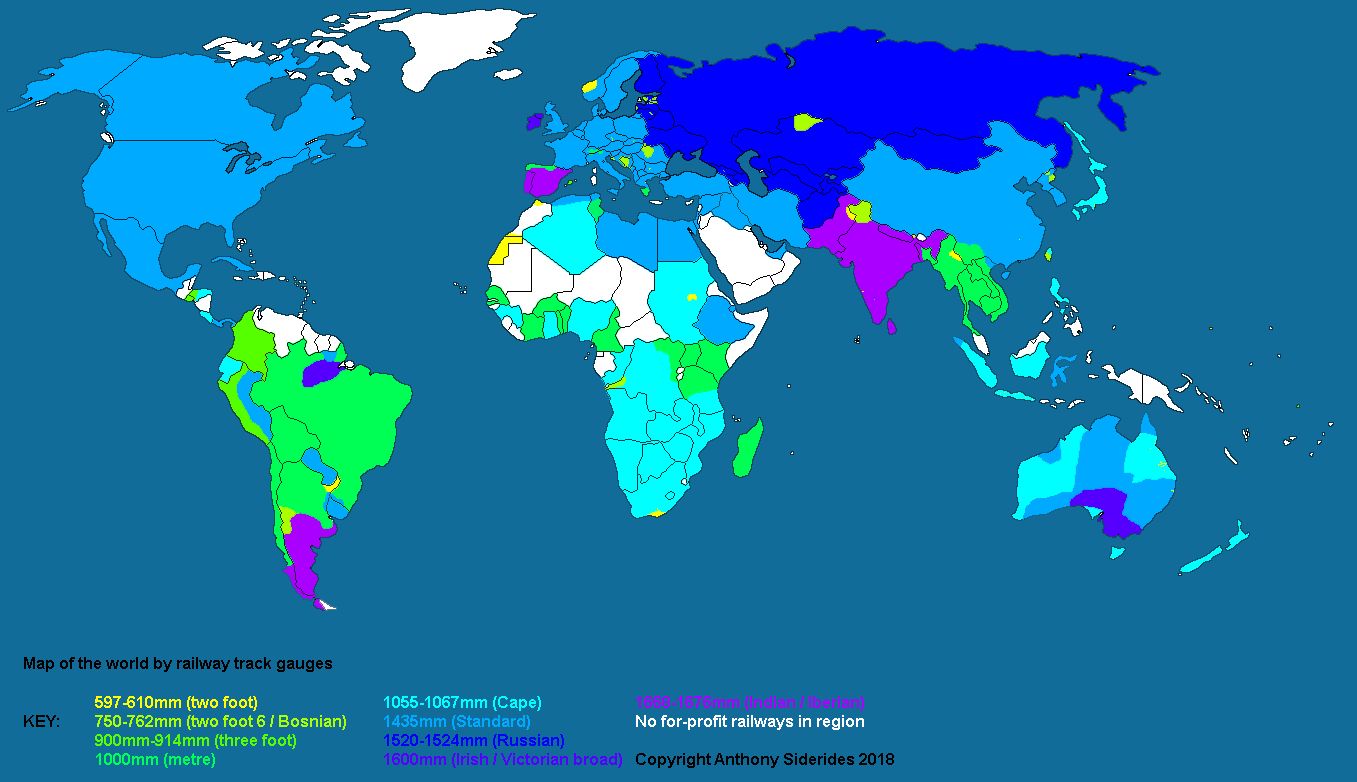

Globally, railway track standards converged, but also with significant exceptions. Standard-gauge railway lines were built across North America, Europe, North Africa, the Middle East and China, but Russia, sub-Saharan Africa, South America and India ended up choosing different track widths.

World gauge map, with standard gauge regions in light blue

Anthony Siderides

If the 1840s railway boom is anything to go by, frictions between different payment systems and worries over incompatible standards are unlikely to hold back the current race over protocols.

In his novel ‘Dombey and Son’, published in 1846 at the peak of the stock market mania, Charles Dickens described a scene of chaos in a working-class area near London’s Euston station.

“The first shock of a great earthquake had, just at that period, rent the whole neighbourhood to its centre,” wrote Dickens.

“Traces of its course were visible on every side. Houses were knocked down; streets broken through and stopped; deep pits and trenches dug in the ground; enormous heaps of earth and clay thrown up; buildings that were undermined and shaking, propped by great beams of wood. Here, a chaos of carts, overthrown and jumbled together, lay topsy-turvy at the bottom of a steep unnatural hill; there, confused treasures of iron soaked and rusted in something that had accidentally become a pond.”

But startling as this destruction looked, it was laying the ground for a new order, suggested Dickens.

“The yet unfinished and unopened railroad was in progress; and, from the very core of all this dire disorder, trailed smoothly away, upon its mighty course of civilisation and improvement,” he wrote.

Sign up here for our monthly newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes