Populist politicians in developed countries aim hostile rhetoric at economic migrants, aiming to deter their arrival. But for those who make it across borders to work abroad, sending money home is becoming easier.

Exploiting the migrants

The World Bank estimates that, on average, money transfer companies consume a whopping 7.1 percent of a typical remittance from a migrant worker to his or her relatives at home.

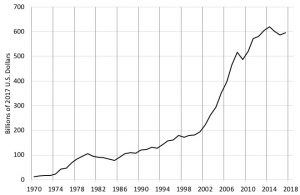

In a global remittance market generating flows of around $600bn a year, this juicy commission comes from hitting migrants with a mixture of fees and non-competitive foreign exchange (FX) rates.

Global remittances

Source: https://voxeu.org/

Cheaper and faster

The remittance business has traditionally been dominated by two US companies, Western Union and MoneyGram, who send payments through their proprietary networks. But it’s now witnessing a real shake-up as new entrants use the internet and mobile technology to make payments cheaper and faster.

In 2017 one digital money transfer firm, TransferWise, became a unicorn (a privately owned start-up valued at over a billion dollars), joining an elite of European fintech firms that includes German direct bank N26, UK digital bank Monzo and mobile payments company Revolut.

Western Union currently makes a 5.5% margin on transfers

The old guard in the money transfer business is far from dead, though. New York-listed Western Union, one of the oldest names in US corporate history, is still the largest player in the sector. The firm handles nearly $80bn a year in remittances and in November, it launched a new digital transfer business to try to head off the fintech insurgents.

Western Union currently makes a 5.5% margin on transfers, nearly seven times more than TransferWise’s 0.8%, according to SaveOnSend, a specialist money transfer blog.

But by comparison with the rocketing private market valuations of many fintech companies, Western Union’s share price is flagging, sitting around 35 percent below a peak reached more than a decade ago.

Investors don’t fancy the long-term prospects for the money transfer incumbents, in other words.

The mechanics of global transfers

Many remittance-focused start-ups, such as TransferWise, Azimo, WorldRemit and TransferGo, are based in London, benefiting from the UK capital’s reputation as the leading global fintech hub.

I recently visited Azimo’s CEO, Michael Kent, at his firm’s offices in London’s Islington.

Michael Kent

Handling an average transaction size of $450 for its clients, Azimo now employs 125 people and has raised $66m across five funding rounds.

For CEO Kent, the launch of Azimo in 2012 was a logical progression: he had spent the previous seven years assembling, consolidating and then selling a chain of high street money transfer businesses.

“When we launched Azimo, we took everything we knew about payments, clearing, the banks’ FX platforms and the new payments infrastructure at many emerging market banks. We started with a clean sheet of paper,” Kent said.

“We wanted to head in the same direction as our customers”

And from the start, the firm was focused on mobile technology.

“Traditionally, people had gone into a store, bought a calling card or rented airtime and pinged their friends on Skype to make a money transfer. But then they were still handing over cash and paying seven, eight or nine percent in commission,” Kent said.

“But we saw more and more people using smartphones and we wanted to head in the same direction as our customers,” he explained.

I ask Kent what how Azimo competes with TransferWise, which last year hired 500 people and now handles £3bn ($4bn) a month in transfers, compared with Azimo’s $1bn annual transfer volumes.

“Our average transfer size is smaller,” says Kent. “What also makes us unique is our pan-European focus. There’s a big migrant population and many migrants currently rely on European banks, who are exploiting them.”

Moving across to the office whiteboard, Kent demonstrates Azimo’s business model with a flow chart.

“We take in money mainly via card payments from mobile phones, rather than bank transfers,” Kent says. He explains why.

“Interchange fees—the fees charged by credit or debit card providers for processing payments—are capped by EU regulators at 0.2% per transaction for debit cards and 0.3% for credit cards, which is a good deal,” he explains, contrasting the US market, where interchange fees are uncapped and often exceed 1%.

Kent then explains Azimo’s anti-money-laundering (AML) procedures, necessary to stay on the right side of the global financial police.

“Our AML software checks a number of variables—for example, the amount you’re sending and where to, where you’ve sent money before, your device ID, where you are opening the app—and then does a risk-based assessment. The transaction is either approved, declined or flagged for further review.”

“It’s not quite free, but it’s very close”

If approved, the money transfer then proceeds to the currency conversion stage. This happens via an automated software link to a bank specialising in currency dealings, granting Azimo’s clients access to near-wholesale FX market rates, says Kent.

“We are plugged into the leading FX banks in Europe and trade at maybe 1-2 basis points (hundredths of a percent) away from institutional rates. It’s not quite free, but it’s very close,” says Kent.

In fact, the typical FX conversion has two legs: via dollars, client funds are changed into the local currency of the recipient of the transfer. The final stage is to distribute the money. Again, this process is automated.

“We have software integrations with the banks who are our payers in emerging markets,” says Kent.

“We ping them an instruction to pay out and they can do so in cash, to a bank account or, in certain markets, to mobile wallets (such as M-Pesa in Kenya). These local banks charge a per-transaction settlement fee, usually between $1-$5.”

I ask how long the whole procedure takes.

“US banks don’t have automated real-time clearing”

“It can take as little as seven seconds, especially if the payment is going to an emerging market with a faster payments infrastructure in its banking system, or if we are paying out in cash at the other end,” says Kent.

And it’s the creaking payments system in the home of the dollar that stands out.

“But a recipient based in the US may have to wait a couple of days for a transfer. They don’t have automated real-time clearing.”

Where will the fintech land grab end?

The rise to prominence of the digital money transfer firms comes against the backdrop of a booming fintech sector and a banking system that’s under pressure.

In one sense, the playing field is stacked against the banks. Private equity investors seem happy for fintech firms to operate at thinner margins than industry incumbents, spending large sums on marketing and client acquisition and incurring steady losses. N26, Revolut and Monzo all lose money, for example.

But in the money transfer business profitability seems easier. TransferWise, for example, has now reported a second year in the black. I ask Kent about Azimo’s financial performance.

“We decided to take all we make and reinvest it in growth”

“We have had a couple of profitable months so far and we expect to be stably profitable by the middle of 2019,” Kent replies.

“If we’d stopped our marketing campaigns that would have happened earlier,” Kent goes on. “But we decided to take all we make and reinvest it in growth.”

Kent expands on the sector’s dynamics.

“For a fintech start-up, the other route to profitability is to keep cheap valuation capital flowing your way,” he says.

“But I do wonder about some of the recent monster raises we’ve seen,” he says, without naming names.

N26’s January fundraising was at an eye-popping valuation of 40 times the company’s revenues, for example, a ratio reminiscent of the dot com era.

Kent turns to fintechs’ path to the public equity markets and the point at which private equity investors and founders cash out.

“What’s going to happen when these start-ups get to the initial public offering (IPO) stage?” he queries.

“IPO investors tend to be pickier about valuations than some venture capital and private equity firms, let alone some of the non-traditional sources of capital for fintech firms—for example, big Chinese institutions and sovereign wealth funds.”

I ask Kent about the potential future role of the social media giants in the payments business. In 2014, the Financial Times reported that Facebook had sought tie-ups with three money transfer companies, including Azimo and TransferWise.

Kent declines to talk about Facebook, but makes a broader observation.

“In the West, the internet has historically been monetised largely through advertising,” Kent says.

“But especially in emerging markets, the internet is now being monetised increasingly through fintech. If you can’t sell people ads, or if you feel ads are too cheap, you can create a digital wallet and make money via payments and commissions on sales,” he adds.

As a business strategy, controlling money flows while collecting and exploiting client data sounds like a winning combination. And while banks may have been left behind in monetising their in-house payments businesses, competitors are on the front foot.

The competitive landscape is becoming more confusing

US firm Paypal, China’s Ant Financial (formerly Alipay) and Tencent (owner of WeChat) are all spending billions on acquiring other money transfer firms.

However, the competitive landscape is also becoming more confusing. As banks have cottoned on to the value of payments in helping establish client loyalty, fintech firms are now heading in the other direction. Kent, for example, makes it clear that Azimo has broader ambitions than just focusing on remittances.

“Over the next three or four years, you’ll see firms like ours offering their clients services like a card, credit or the ability to trade in other financial products,” Kent predicts.

Kent and his business partner, Ricky Knox, have hedged their bets in another way: as well as founding Azimo, which for now has an e-money institution licence only, the two have invested in a challenger bank, Tandem.

With technology firms entering payments, payments firms shifting towards banking and banks aiming to fight back against the outsiders using their data, we are seeing a convergence of activities that typically challenges lawmakers and regulators.

But for the time being the consumer—long the victim of international money transfer firms—appears to be a clear winner.

Want to receive the New Money Review newsletter? Sign up here.