A recent payment fraud started from a gym theft. The story contains valuable lessons about mobile security.

In an article I wrote for New Money Review last year, I uncovered some alarming vulnerabilities in mobile phone security–specifically, regarding the safety of the money in the mobile banking apps that most of us now use.

Testing an iPhone with different apps, I showed that a criminal with knowledge of someone’s phone PIN and in possession of that person’s phone could reset security steps like Face ID and the account password quite easily, then loot the unfortunate victim’s bank accounts.

It’s not that difficult to “shoulder surf” someone’s PIN and then take their mobile phone, especially in a crowded place like a bar or club.

It’s not that difficult to “shoulder surf” someone’s PIN

And, I showed, some apps posed more risks to users than others. There is no single standard in this relatively new technology of phone-based biometric security. This unevenness makes the job of app developers, security experts and law enforcement harder, and it throws up new opportunities for resourceful criminals.

Recent evidence suggests the mobile phone firms are aware of the problem, and are trying to deal with it.

In the latest version of its iPhone software, called “iOS 17.3”, Apple has included something called “Stolen Device Protection”.

It requires biometric authentication (a face or fingerprint scan) to access the phone when you are away from trusted places like home and work. And it includes a time delay for a second biometric authentication if you are taking certain actions that are particularly risky or sensitive (like changing your Apple ID password, changing the passcode for Face ID or Touch ID or seeing saved passwords).

Will this new security step prevent thieves in possession of your phone from emptying your bank or payment account? To answer this question, I updated my phone to iOS 17.3 Beta and reviewed the apps I had studied in my last article.

But first, a recent criminal case helped me decide what checks to include in my investigation.

New modus operandi

A few weeks ago, the Daily Mail published a story about a couple who stole gym members’ bank cards from their lockers and used £250,000 of stolen money to go on expensive shopping holidays to Dubai.

“Ashley Singh, 39, and Sophie Bruyea, 20, targeted 18 victims as they worked their way through lockers at several gyms across London and the south-east in a year-long crime spree,” the Mail reported.

This story caught my attention, as I spend my life studying cards and their vulnerabilities. It’s not so easy to exploit card thefts to that kind of total. Clearly, the stolen £250,000 was not spent in one go.

First of all, a large volume and number of unusual transactions, especially halfway around the world from where the victim lives, would probably be blocked by a bank. Second, if a thief had taken a card, surely the cardholder would report it as stolen and ask for it to be blocked and replaced. Finally, few people usually keep thousands of pounds in a card account.

So there was probably more to the story than the opening paragraph suggested. And, further down its article, the Mail gives a clue as to what might have happened.

“The couple would visit the gyms and rifle through lockers where gym goers’ bank cards and even SIM cards were stolen while the unassuming victims were exercising,” the newspaper reported.

“They may have been able to empty accounts because the swiped SIM cards gave them a way to request password resets on the stolen cards,” it went on.

“In addition, many phones are now set up to pay cardless for items, meaning the SIM may have allowed them to set up the system on a new handset.”

Let’s imagine what a thief could find in a gym locker

Now, that’s the kind of thing I investigated in my last New Money Review article–payment apps on phones.

Let’s imagine what a thief could find in a gym locker. Most of the keys to cracking your digital life are probably there: your driving licence, containing your name, date of birth and home address; your bank card; and a SIM card, together with your phone.

If the locker thief hits the jackpot, he or she might even find your phone passcode written somewhere in your notepad or on a piece of paper stored in your wallet.

Is this collection of your personal information really enough to steal all your savings? Pretty much so!

Revisiting payment apps for vulnerabilities

I revisited the mobile payment apps I had surveyed in last year’s article to see what the requirements were for getting access to a victim’s funds, assuming I had possession of certain types of personal information.

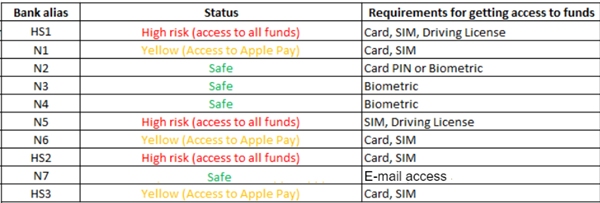

The results are in the table below: the aliases in the left-hand column are for apps offered by traditional, high street banks (labelled “HS”) and those offered by newer, “neo-banks” like Revolut or Wise (these are labelled “N”).

It’s worth noting that most neo-banks are not banks. This means that your money is not covered by state deposit insurance.

What do the results in the table mean? Let’s examine the colour coding in the middle column.

If a cell is formatted in red, my research suggests you can get access to the whole bank account with everything the Daily Mail criminals likely found in the gym locker.

Everything starts with a stolen card, like the article suggested. But the criminal would not just go and tap that card in a supermarket (or, more ambitiously, try to use the card in a store to buy a laptop or a car).

Instead, the criminal would use the card to find out the victim’s bank or neo-bank. Then the criminal would likely remove the SIM from the victim’s phone and insert it into their own phone (there is a security step here, called a SIM PIN, which should stop anyone doing this, but no-one uses it anymore, or the SIM PIN is set to a default 0000).

Finally, a driving licence containing a valid date of birth and a postcode is very helpful for banks that ask for these pieces of information during an account reset.

This attack is extremely easy and fast to execute

This attack is extremely easy and fast to execute and poses a serious threat to a phone owner, whether you have an iPhone, Android or even an old-fashioned Nokia.

We were able to execute the attack against at least three banks. Surprisingly, we even found a neo-bank that did not ask for biometric verification during the registration of the PIN on a new device.

Once the criminal has logged into your bank account, you can expect him to empty it.

A second scenario applies to the cells formatted in yellow.

In this case, thieves enrol in an Apple Pay or Google Pay (GPay) wallet on their own phones using your card details, so conveniently left in the gym locker.

This turns out to be great for the criminals, though not for you

This turns out to be great for the criminals, though not for you. First, payment apps like Apple Pay and GPay have no transaction limits at all (whereas contactless payment card transactions in the UK carry a £100 per transaction limit).

Worse, if anyone uses Apple Pay or GPay for a scam, it’s more difficult to get your money back than if the criminal were draining your bank account directly.

First, there’s the absence of transaction limits, meaning that any fraud could be substantially more costly.

Also, the bank or neo-bank whose payment card is enrolled in Apple Pay or GPay often has insufficient information to create an effective set of anti-fraud rules. This is because banks’ anti-fraud algorithms rely on access to granular information on individual transactions. But if you’re using Apple Pay or GPay for payment, those tech firms may keep the most important transaction details to themselves.

Further, if a criminal can enrol an Apple Pay or GPay wallet on their phone that’s linked to a stolen card, the victims won’t get any notification of transactions. One day, someone, somewhere, will make a £10,000 payment that the victim will find hard to claim back.

Finally, to add a card to Apple Pay or GPay wallet, a lot of banks like to send a one-time SMS with a code to validate the card’s ownership. We are assuming that the thief has got your phone and can put your SIM card into another handset, so this doesn’t present a real obstacle.

Cells in the table highlighted in green indicate that the payment app provider was doing its job, and it wasn’t possible to bypass biometric verification checks, even with stolen ID documents, cards and a stolen phone.

Thinking through defences

Our research has shown that payment apps’ defences against theft and potential fraud are uneven and, in some cases, full of holes. Assuming that the criminal has access to your phone and some other personal data, at least 60% of the apps we investigated could leave you with an emptied account.

At least 60% of the apps we investigated could leave you with an emptied account

So let’s reconsider some basic security principles to think how we might protect ourselves.

A simple and very helpful maxim tells us not to put all our eggs in one basket. Let’s look at the examples we’ve shown you and think how we might protect ourselves better.

First, let’s revisit how banks handle requests by clients to reset access to their accounts. Ten years ago (and this is still the case with some high street banks), it would tell you to go to a branch. Once someone could validate your ID face-to-face at the branch, you would regain account access easily.

But this is increasingly difficult to do with high-street banks, given the progressive disappearance of bank branches. And physical ID verification is impossible at neo-banks–they simply can’t offer this service.

Instead, your identity verification will probably consist of some or all of the following steps, carried out remotely. It will involve the provision of:

- card details–the long card number, expiry date and security code;

- personal details–your full name, date of birth and address;

- a one-time code sent to your mobile phone or email account;

- secrets, such as a secret word or your card PIN;

- biometric verification, including sending a video of yourself and a photo of your ID.

To summarise, every bank or neo-bank chooses a mix of these pieces of information to create a multi-factor authentication process. This involves you showing that you:

- Know something, such as a password or PIN;

- Have something, such as a bank card, ID or access to your email;

- Are something, which can be checked via biometric verification.

Once you don’t know something (such as your login and password), banks ask you to replace that with something you have, or you are.

In theory, multi-factor authentication of this type should be enough to protect you. But the gym locker thefts, combined with the inadequate security I have demonstrated at some payment apps, show that there are ways for clever criminals to get access to your money, all the same.

Never keep these items together in a place where they might be stolen

What should I do?

The best way to protect yourself is to prevent criminals from gaining access to your payment card, any form of ID and a phone all at the same time. So never keep these items together in a place where they might be stolen.

A gym locker is probably the worst place of all to put things (even though most of us probably do leave these items there together). You are liable for any of your belongings left in the locker and the gym owner’s terms of use will likely rule out any responsibility for thefts.

Finally, a simple step that could easily act as a last line of defence: set a PIN for your SIM card.