Some frauds and scams aimed at emptying your bank account are ringing alarm bells. But what about the ones that aren’t?

Authorised push payment fraud (APPF) – where the victim is tricked by fraudsters into sending money to them (usually online) while the fraudster poses as a genuine payee – costs the best part of £1bn a year, and that’s in the UK alone. Only around half of the victims get their money back.

But what about an arguably more alarming fraud? It’s where a criminal gets hold of your phone and then manages to steal your funds. That kind of theft could happen to any one of us – in a bar, club, crowded rail carriage or even in the street.

Surely our phones’ security features and those built into our banking apps would protect us?

Blamed for being a theft victim

Apparently not. In January, I read about a man who said he had been hit by just such a theft. And his bank didn’t reimburse him. It blamed him.

Jacopo de Simone’s mobile phone was stolen from his pocket in London in May 2022. His device had been locked and password-protected. But still, said de Simone, the thieves had managed to steal £22,500 – all the money in his current and savings accounts.

His bank didn’t reimburse him. It blamed him

His bank said this kind of theft was impossible unless he had shared his PIN with someone in advance. It accused de Simone of ‘gross negligence’, he says.

De Simone countered: “I don’t access my phone using a PIN code – I use facial recognition. My Barclays PIN is different to my phone PIN and they’d need to have both of them.”

This story piqued my attention. But none of the details added up. So I decided to investigate.

Anatomy of the attack

Let’s review the scam in steps.

The BBC, which reported de Simone’s case, asked cybersecurity expert Dr Jessica Barker to break down the anatomy of the attack and to challenge the victim’s statement. She said one phone scam scenario might involve these steps:

- First, criminals ‘shoulder surf’ a victim to learn their PIN

- Then they steal the phone

- They use the PIN to unlock the phone and then try the same PIN to access banking apps

- If unsuccessful, criminals search the phone’s notes section for banking passwords or PINs

That sounds plausible, but it didn’t address Mr. de Simone’s assertion that he had been using Face ID to log into his banking app.

Anyway, I started my investigation by framing the following question and testing it on ten banking apps (three from high-street banks and seven from so-called ‘neo-banks’): “How easy is it to move money from the app if someone has the phone and the PIN?”

Test conditions

There were some additional conditions that I used in the test. Here they are:

- We have the latest version of Apple’s mobile operating system, iOS, and the latest versions of the banking apps. We have also set up Apple’s biometric authentication (Face ID) and have enabled the biometric login on the app, if possible. To avoid making the analysis too complex, we stuck to Apple/iOS in the investigation. Google (Android) has different set-up conditions in its phones, but I believe Android devices are equally exposed to some of the potential attacks I describe below.

- We assume the criminal has the iPhone and knows its PIN but doesn’t know any other PINs or passwords in other banking apps on the phone.

- The criminals have access to the email app on the phone. The Gmail app, for example, does not have a separate PIN and allows you to see every email once the phone is unlocked. Another example, the Mail.com app, can be protected by a PIN, but this feature is not enabled by default.

- The criminals are able to receive and send SMS and/or automatic voice calls.

Our results

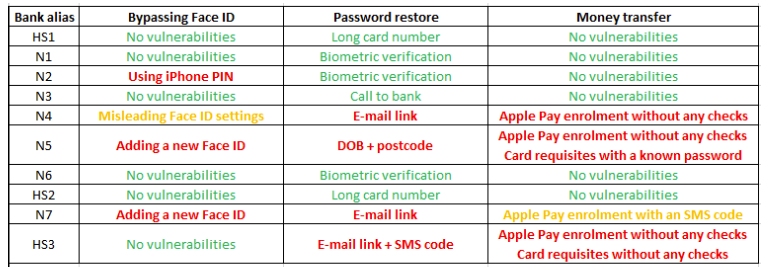

In the left column, I labelled the banks HS1-3 (for the high-street banks) and N1-7 (for the neobanks).

In a nutshell, some apps allow a potential criminal to bypass Face ID and reset the account password quite easily. These cases are highlighted in red in the table. Once criminals unlock the device, they can drain the accounts within minutes.

Some apps allow a potential criminal to bypass Face ID and reset the account password

Other apps require additional information, such as date of birth, address or full name, to reset the account password, and these cases are highlighted in orange. But usually, this information can be obtained on the very same device.

Finally, six out of the ten apps showed robust enough measures to help you not lose money if you become a robbery victim.

In the spreadsheet, columns 2-4 show the three steps of the attack we emulated, and what we found. Here is some more detail on each of those steps.

Step 1. Bypassing PIN or Face ID in the banking app

This can be done in two ways: by presenting the iPhone PIN (the N2 app allows us to do this) or by adding a new Face ID pattern. Most of the apps will ask the phone user to enter a PIN or password if a new face has been added. This doesn’t stop the criminal, unfortunately, who can now try Step 2.

But two apps – N5 and N7 – didn’t ask for a new PIN or password, allowing a freshly added face owner to log into the banking app.

Another interesting example is the N4 app – even if the victim sets up the “Use Face ID” feature, it won’t be required unless a second, so-called “Auto-lock” feature is enabled (for more on this security flaw, see below).

Step 2. Resetting the password

Instead of trying to log into the existing account, criminals can press the ‘Forgot my password’ button. Different banks require different pieces of information to reset the password/PIN. Broadly speaking, these ‘secrets’ can be divided into three categories:

- Know something (e.g., password, PIN, SMS, email, name, date of birth, address)

- Have something (e.g., ID, credit card number, access to phone)

- Am something (biometrics, e.g. a selfie or a video sample)

Based on our conditions, the weakest security checks will be those that require access to the same stolen phone, allowing us to reset the password by SMS or email. And in this case, the apps N4, N5 and N7 were the least resilient – they used emails and SMS to reset the password.

The N5 app is somewhere in the middle – it requires knowing the date of birth and the postcode. But this is something that can be easily pulled out of emails.

Fortunately for the criminal, there are a few options to move money

Step 3. Moving funds

Finally, once the criminal has control of your banking app, he/she needs to drain your account. Fortunately for the criminal, there are a few options to move money.

- Make a wire transfer to a new recipient. For example, the fraudster could use SEPA – instant credit transfers that allow for real-time payments from any eurozone country to another. Wouldn’t this leave a trail that could implicate the criminal? Not necessarily. For example, the criminal could transfer the money to a ‘mule’ and withdraw it for a fee (to the mule). Or the criminal could send the money to already compromised accounts whose owners won’t know about your malicious intentions. Or, as Mr. de Simone found out, the bank may blame the original owner of the phone. By the time the dust settles, there will be no money and no trails.

- Get card details to pay online: for example, order something from Amazon. Here, 3D Secure–a way of ensuring extra security in card payments–won’t help, as the one-time code that authorises the payment will arrive on the same stolen mobile phone or in the app. Another option for the criminal who has card details and access to one-time codes is to move money using any card-to-card service, such as PaySend.

- Issue an Apple Pay wallet on the stolen phone. Let’s focus here on how to monetise using this functionality, and we will show in detail how and why criminals can enrol the card itself in the next section. If a criminal knows your phone’s PIN, he can access your Apple Pay wallet, go to a fancy store and buy anything he wants, with no contactless limits. Or, similar to the previous option – he/she can use Apple Pay to pay online, for example, paying for something on eBay using the Apple Wallet.

Details of two of the attacks

N4 app

Let’s see in more detail the steps that criminals can take to succeed in their heists. First, we focus on the N4 app, issued by a neo-bank.

The problems begin with a lack of Face ID authentication when you’re logging into the app. Amazingly, this happens even though the settings say differently.

Face ID or no Face ID?

On investigating, I found that you needed to turn on the “Auto-Lock security” option for the app to ask for Face ID.

After opening the app, the criminal needs to drain the account. We described three common options to move money out of compromised accounts: wire transfer, card transactions or Apple Pay.

When I played around with N4’s app, I found I couldn’t use the first two options as by now the app was – correctly – asking for Face ID.

So I focused on enrolling Apple Pay instead. It turns out that this is one of the most popular routes for those wishing to extract money from a stolen phone’s banking app.

Apple Pay can be enrolled through the ‘Wallet’ app on the phone by entering the card number, security code and expiry date, or via an “Apple Pay” button in the banking app the criminal has gained access to.

Banks that don’t use one-time codes are known targets for criminals

At this enrolment stage, Apple has always allowed each bank to decide what additional security is required. The most popular option is to request a one-time code. But some banks don’t do that for convenience, even if the card is enrolled via the Wallet app, and Apple has never objected to that because their motto always was “We provide a payment platform, and everything else is not on us”. Banks that don’t use one-time codes are known targets for criminals.

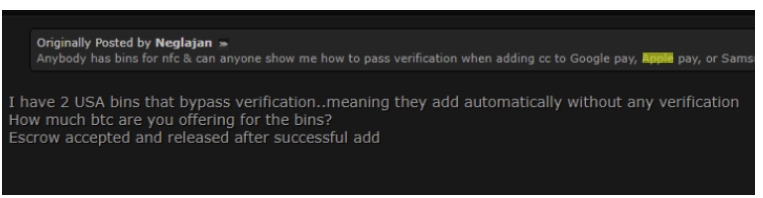

On dark web forums, you can find the target banks quite easily (in the screenshot, ‘BIN’ refers to the first 4-6 numbers on a payment card, which identify the card issuer).

Offering from one of the dark web forums about banks

Other banks request one-time codes when you are seeking to enrol their card into Apple Pay by entering the card number, security code and expiry date. But they don’t do so when the card is enrolled via the ‘Apple Pay’ button in the app. This is because they presume that the security measures that have been required to get to this point, like Face ID or PIN, are a good enough barrier.

Unlike contactless bank cards, Apple Pay has no limit

In summary, you don’t even need to know any card details if you use the Apple Pay button in the banking app.

In the case of N4’s app, it didn’t ask for a Face ID for me to enrol Apple Pay.

Once they’ve done this, criminals can use Apple Pay as long as they know the phone’s PIN! As a reminder, unlike contactless bank cards, which still have relatively low transaction limits, Apple Pay has no limits. So if you’re prepared, you can go into a dealership and buy a car. Or you can go to a fancy store and spend a couple of grand. But you should be able to drain the account pretty quickly.

This video shows how I clicked on the button within the N4 app to add it to an Apple Pay wallet.

HS3 app

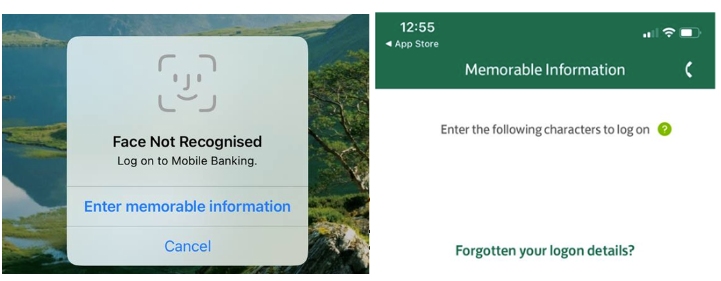

This app did not allow me to log in if a Face ID was deleted and reissued. However, the app has other flaws. This is what I saw when it didn’t recognise a new face.

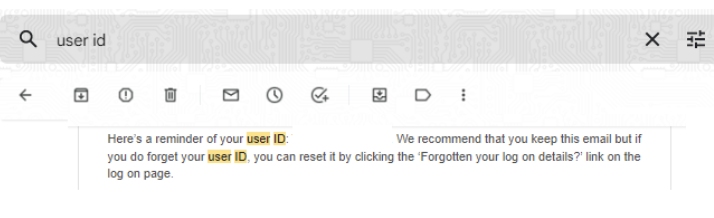

It’s quite handy that the bank is happy to share a User ID in an email, don’t you agree?

Failed Face ID–what next?

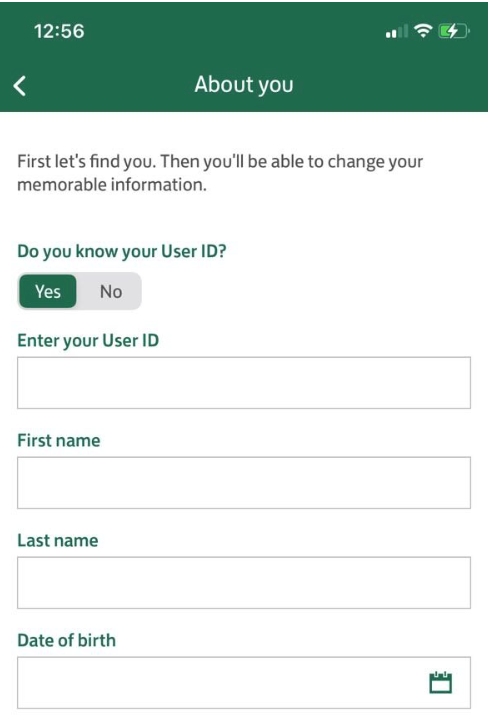

So, following the prompt, let’s try to reset the login details! What would a criminal need for that?

Resetting the User ID

All of these details are easy to find in the email account. It’s quite handy that the bank is happy to share a User ID in an email, don’t you agree?

Bank User ID found in an old email

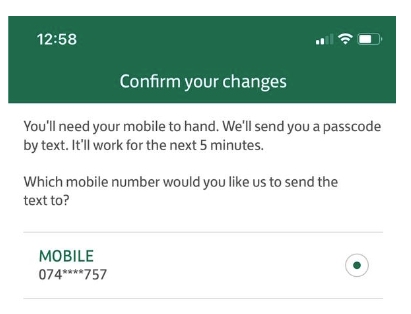

Once this information is obtained, it’s possible to reset the password:

Resetting the password

The final step for the password reset is a one-time code that will arrive – unfortunately for the victim – on the stolen device.

Game over. Once the criminals have set up a new password in the app, they can drain the account any way they want: get the card details, enrol Apple Pay or make a wire transfer. No additional checks are required to get card details or to enrol Apple Pay. To make a wire transfer, criminals will need a password – the one they’ve just set up themselves.

The aftermath–and a worrying future

In February, the Wall Street Journal wrote that giving a criminal your iPhone and its passcode was equivalent to opening a treasure box.

That article pointed out a few other vulnerabilities:

- If criminals know the victim’s PIN, they can use the already-issued Apple Pay cards on the phone

- Criminals can use the phone to apply for credit using apps like Klarna or Apple Cash. At New Money Review, I’ve already written about the security weaknesses in some of the ‘buy-now-pay-later’ (BNPL) apps that offer such credit.

- Signing out of ‘Find My Phone’ and changing the password will make the victim’s life 100 times harder.

Alarm bells should be sounding amongst banks, payments firms, tech giants, app developers and the authorities.

But I’d say that the results of my research go further. I’ve shown that, contrary to what one UK bank reportedly told poor Mr. de Simone, it’s quite straightforward to use the combination of a stolen phone and its PIN to loot victims’ bank accounts. This can be done by resetting their banking app log-ins, using a variety of exit routes. Alarm bells should be sounding amongst banks, payments firms, tech giants, app developers and the authorities.

To reduce the risks of losing money right after losing your phone, we strongly recommend the following:

- Enable Face ID and a long (6+) PIN code on a phone

- Set up a different PIN code in every app you can, e.g. mail or banking apps.

- Do not store your card with your phone. Mag Safe wallet is a bad idea.

- Do not leave personal details on the phone. That includes photos and records of your documents, PINs, logins and passwords. Your photo app, file downloads and your email account are often full of such details, so you need to make a special effort not to leave them there.

Disclaimer

For obvious reasons, I haven’t named the three high street banks and the seven neo-banks whose apps I tested. All the vulnerabilities were reported to those firms’ security teams prior to the publication of this article (assuming I could find a public security email, security.txt file, responsible disclosure program or something similar). Not all the neo-banks, however, offered any such way of getting in contact.

More from Tim Yunusov at New Money Review

Adding crypto to payment cards is playing with fire

Buy now pay less or…not at all

Fake IDs blow hole in Russia sanctions

Don’t miss our podcast, “the future of money in 30 minutes“, featuring the top minds in payments, digital currency, crypto, law, technology and financial crime