How criminals can profit from shared liability

BNPL (Buy Now Pay Later) is a type of short-term financing allowing consumers to make purchases and pay at a later date (often interest-free).

It’s been one of the great financial technology (‘fintech’) success stories of the last decade. BNPL loans have soared in the last couple of years as consumers took advantage of a promise to get goods for a limited upfront payment.

24 percent of Europeans now use BNPL at online checkout. But BNPL is now preoccupying regulators as rising interest rates and concerns over bad debts have caused the value of key BNPL players like Sweden’s Klarna to crash.

BNPL has added convenience for consumers, though it’s also been put to questionable uses. In a recent case, a US-based BNPL provider called Credova offered no-interest loans to buy guns and ammunition under the marketing slogan ‘shoot now, pay later’.

Fraudsters are never slow to jump on a new tech trend

And there’s another thing to worry about when it comes to BNPL. Below I will show how simple it is to use stolen identities to take money from any merchant that supports BNPL companies as a payment mechanism.

Fraudsters are never slow to jump on a new tech trend, and at this point, several well-documented fraud schemes against BNPL either use stolen card details or delay payments to the merchant.

After my previous work in synthetic identities and card fraud, I looked at how criminals could utilise security gaps to steal money from BNPL providers. And I was shocked by how little effort is required to amplify synthetic identity fraud and bring lucrative criminal schemes to the next level.

Step 1. Issuing a card using a fake identity

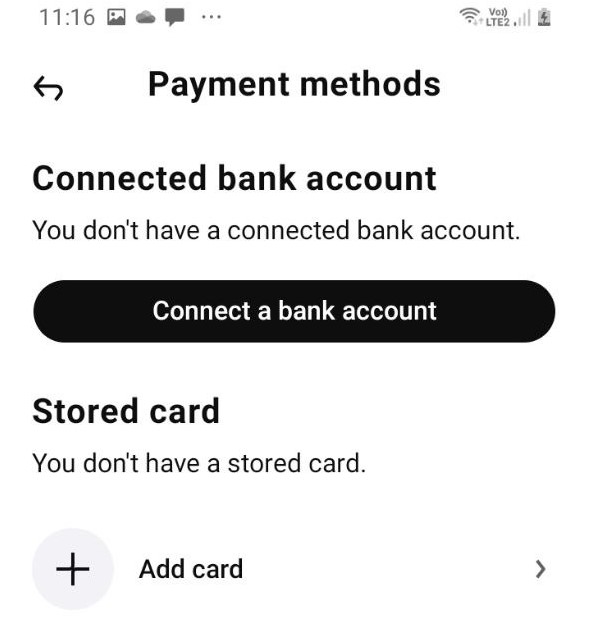

For the BNPL provider I chose, the registration process starts with adding an existing debit or credit card.

Using a stolen card for this step is infeasible for many BNPL providers, including the one I picked. That’s because most European payment services now require proper 3D-Secure verification (they send a one-time code to a separate device of yours before authorising a payment).

But adding his or her own card to the BNPL app as a source of funds would leave an unnecessary trail that could eventually lead to the criminal. What if there were a way to create a Visa or MasterCard card with no link to the real identity? Would criminals be happy to use that advantage against BNPL providers?

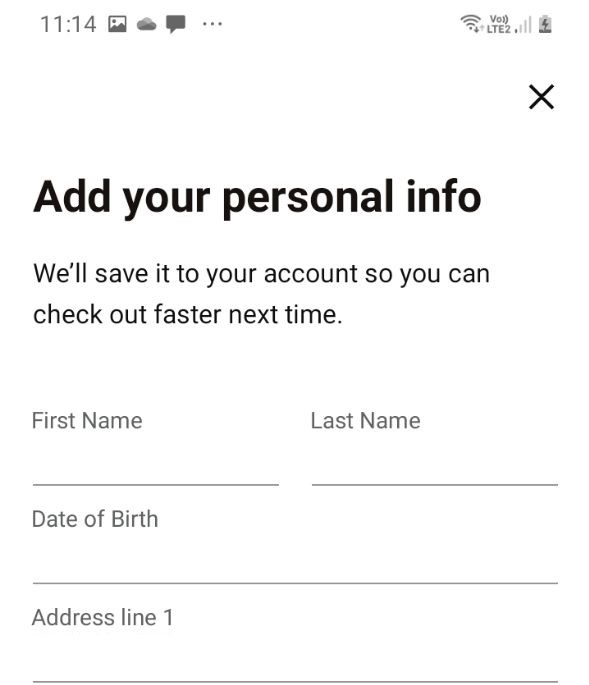

So instead of using one of my own cards, I issued a new Samsung Pay+ (virtual) card, without any formal verification, using my friend’s name.

I showed how easy it is to spend up to £100 on a card set up with a fake ID

Even if you don’t have a willing friend, it’s relatively easy to perform this step. In a previous New Money Review article, I showed how easy it is to spend up to £100 on a card set up with a fake ID.

This is because certain fintech apps (like Samsung Pay+) use a customer identification process called ‘progressive know-your-customer (KYC)’ when onboarding new clients. They don’t ask for the standard proof of identity (passport, utility bill, liveness check) until you spend more than that first £100.

I still need another–legitimate–card to fund the scheme. This time I will use my own card to add funds to the Samsung Pay+ card. Does a criminal still need to provide a real identity? We will come back to that later.

Setting up a fake BNPL account

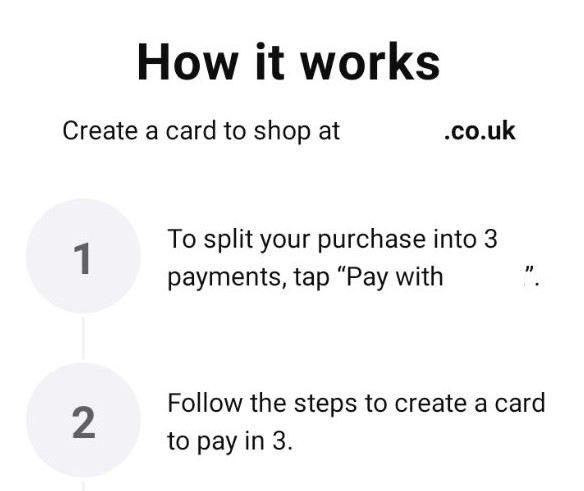

Step 2. BNPL registration using a newly issued card

If Facebook were to offer you a BNPL scheme, it would likely know everything about you: your salary, your outgoings, even when you are likely to die (and default on the payment). But the BNPL provider I picked didn’t have such information about me.

Instead, the provider just asks for a valid card to ensure that the customer is genuine. To keep its customer retention levels high, it won’t carry out proper KYC checks either, meaning no proof of address or proof of identity is required.

So, if I were a criminal, I’d buy a fresh SIM card and use the same approach as in my previous New Money Review article, picking information about some existing individuals from one of the public UK databases.

It’s the easiest way to get a correct name-address match. If a criminal could discover the date of birth of a potential victim, even better. That would bring him to the desired card enrolled under a fake name.

At this point, you may ask: surely you can’t just look up someone’s name and address in a public database and then use it to create a fake ID. Well, money laundering expert Graham Barrow has been pointing out for years just how easy it is to do this using the Companies House database.

In a recent case, fraudsters stole the identities of a civil servant at the UK Ministry of Justice and an employee of the UK’s tax authority to set up shell companies (for likely use in money laundering). You can’t say that criminals don’t have a sense of humour.

So now we will add the card that we just issued (with a fake ID) as a source of funds in a BNPL app. Again, this card has nothing to do with me – if a debt collector decides to find me having information that I left in the system, they will struggle to do that. In other words, we could use anyone’s personal details to issue a virtual card and create a BNPL account.

You don’t need too much information to create a BNPL account

Step 3. Buying products

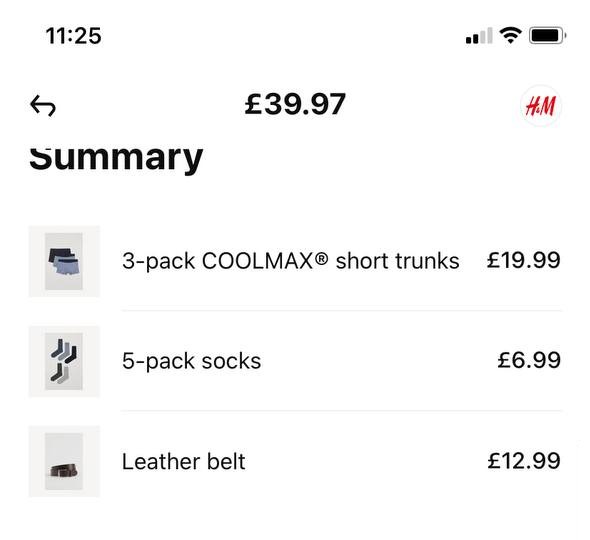

Once I set up a BNPL account, I looked at the list of stores that work with that provider to find a victim. I ended up picking the popular high street store H&M.

Criminals try to maximise their benefits and turnover rates. Buying gift cards would probably be the way of making the most money from BNPL fraud. H&M, though, does not allow purchases of gift cards using the BNPL scheme (which is smart of them!)

So the next best option from the criminal’s perspective is to buy expensive but popular gadgets (iPhones, iPads, Nintendo, etc.). But my ‘purchase’ was more modest: I simply decided to upgrade my socks and collected almost a £50 basket.

My BNPL basket at H&M

When you shop online, you have a billing address and a delivery address. A lot of checks are made around the billing address. If a customer sets one billing address in the BNPL app and a different billing address in the checkout form, the BNPL provider may notice that and the purchase will be suspended. But the delivery address could be anything.

Obviously, criminals would not order products using their real address, but using public addresses with easy access instead, such as a hotel reception or an apartment block with a concierge.

A lot of stores using BNPL services provide the perfect option for fraudsters: you can choose “collect from the store”

In the Lichtenstein/Morgan case currently being prosecuted in the US (the two are accused by the Department of Justice of having stolen more than $5bn in bitcoin from the crypto exchange Bitfinex), the alleged fraudsters apparently did just that: they ordered goods (probably fake passports and IDs) online, then picked up the packages anonymously from hotel receptions and post offices.

But we don’t need to go to those lengths. A lot of stores using BNPL services provide the perfect option for fraudsters: you can choose “collect from the store”.

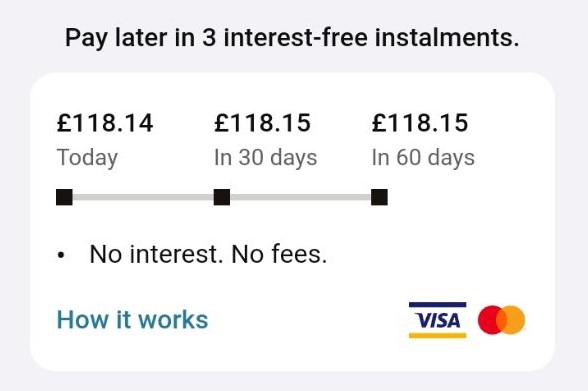

The bottom line is that as long as the billing address in the basket is the same as the address in the BNPL system, you won’t get banned or checked. At the “checkout with the BNPL provider” step, depending on the current risk calculation, criminals then have a few options: pay 25% or 30% now and the rest within the next few weeks, or pay everything in 30 days’ time. Both of these options are quite lucrative if you do not plan to pay in the end.

BNPL providers offer to split payments into three across 60 days or postpone the full payment for 30 days

Step 4. Getting away with fraud

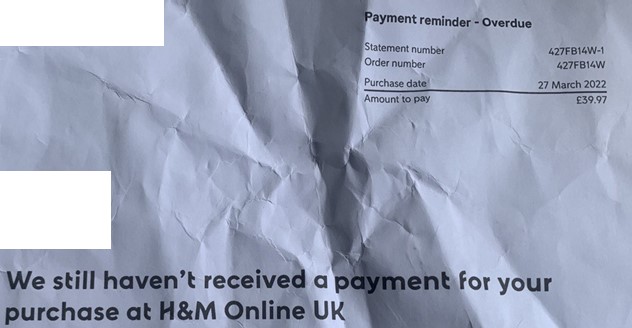

Fraud has been committed. What’s next? In 30 days, when a customer refuses to make his next payment, he will fall into a default category. Whose fault is that? Under current UK regulations, merchants are liable for any BNPL defaults. Most BNPL providers do not take responsibility for fraud risks; for the few that do, it’s a gesture of goodwill.

When a criminal refuses to pay, the victim of identity theft will receive a rather confusing–and alarming–letter

Now, let’s imagine that a merchant decided to sell the unpaid debt to a debt collecting agency that’s very eager to find the criminal. And it’s possible, in theory, that they could do so if the criminal had used his own card, as I did this time.

if I were a debt collector, I’d put this case away and focus on something easier

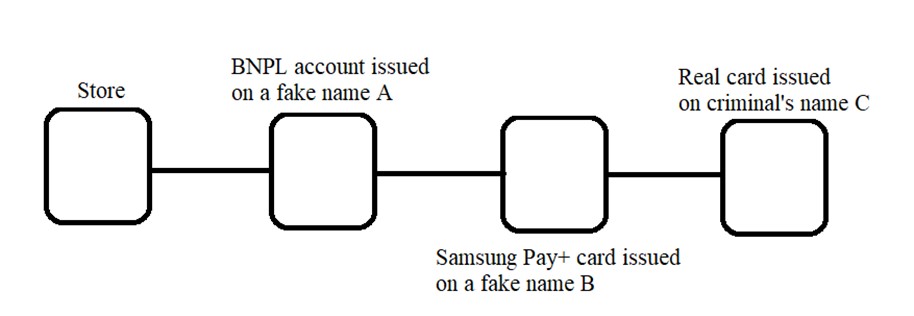

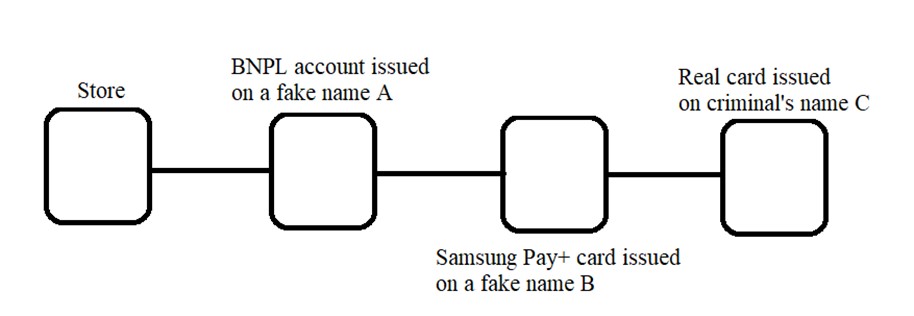

But let me remind you of the long chain of instances involved in the crime:

- the real criminal’s card that funded the Samsung Pay+ account. This card is the only piece of evidence that could lead to the fraudster;

- the Samsung Pay+ virtual card, issued under a fake name;

- the BNPL account that’s also issued under a fake name:

Simply speaking, if I were a debt collector, I’d put this case away and focus on something easier.

And that’s not the worst of it. What if criminals could hide their traces fully? It’s not impossible. See my article, “how easy is it to get a debit card using a fake ID?”

What can we do to stop this type of fraud?

Modern fintech implements its services within the existing payment systems: mobile point-of-sale (POS) providers integrate themselves between acquiring banks and merchants, BNPL providers are wedged between merchants and customers, and mobile wallets and other gadgets sit between the customers and their issuing banks.

But every time, fintech companies try to avoid taking any liability. The fintech ties itself to the payment chain and to its profits but prefers to share the risks and responsibilities. I see a pattern here: shared responsibility means no responsibility.

The right way to address fraud risks would be to determine the liability of every entity in the BNPL chain according to their functions, technical capabilities and revenue shares.

shared responsibility means no responsibility

For example, mobile payments like apps Apple Pay or Google Pay take a big slice of every executed payment. But in any fraud cases involving those firms’ devices (and we all pay by phone these days), their stance towards the fintechs is: “We just provide the infrastructure, it’s your name and logo on the technology!”

The same is true with BNPL: they’re not going to make KYC verifications, and neither are their customers, the merchants. Instead of that, they rely on the fact that it’s “impossible” to issue a debit card without proper verification. But once you have a black sheep in a herd, all your strategy falls apart.

Tim Yunusov is a senior security researcher with application security and offensive research experience since 2009.

He specialises in the security assessment of payment systems (online-, core- and mobile banking, ATM, POS, credit card processing). He is the author of security research and security articles and one of the organisers of Payment Village.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content from New Money Review

Kleptocratic money flows may kill democracy

The battle over financial privacy

Companies and partnerships launder most dirty money

Fake IDs blow holes in Russia sanctions