Amidst the escalating war in Ukraine, Western countries are seeking to step up sanctions against Russia-linked entities. But sanctions can only be enforced if the dividing line between permitted and illicit financial activities is well-defined. And as Timur Yunusov explains in this guest article, it’s not difficult for ingenious hackers to find their way around the rules.

In my work as an information security researcher, I test the systems of banks and financial institutions to see how robust they are.

The organisers of the recent Hackron security conference, held in Tenerife, asked me to prepare a presentation about criminals’ offerings on the dark web related to bank accounts opened using fake IDs. This article is a summary of my findings.

***Warning*** do not do any of the things I describe below at home! If you do you may lose your credit rating, your bank accounts and invite scrutiny from the authorities.

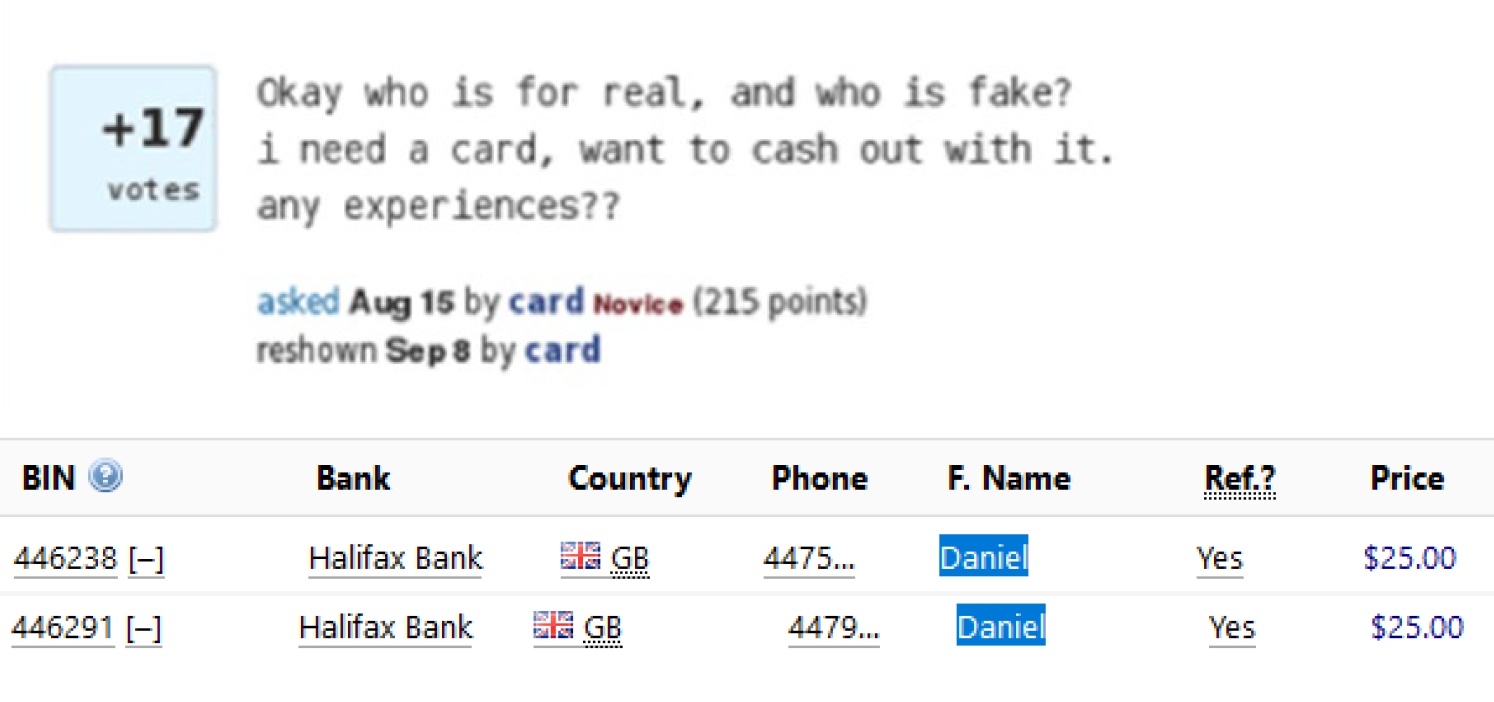

The most popular card offerings amongst cybercriminals include selling data from a stolen credit or debit card (the card number, the expiry date and the CVV code) to buy something using someone else’s money.

You can buy such stolen card information on dark web sites. The offering is sophisticated: when purchasing card details, you can even search for a specific bank, a specific location or account opening date.

Stolen card details for sale on the dark web

There is a good protection against this kind of fraud: 3-D Secure, where you have to confirm a transaction after receiving an SMS message sent to your phone.

But in the US a cashier may give you the opportunity to type the card details on the payment terminal and you can make a purchase. There have been similar frauds on retail sites like Amazon.

Another popular fraud scheme involves cloning the magnetic stripe of a legitimate card, replicating it on a duplicate card and using that duplicate to withdraw cash from an ATM or to make an in-store purchase. Again, this type of fraud depends on a merchant using older payment systems (those not using a form of security called EMV).

(You can read more about card-not-present and magstripe fraud, and the means of preventing them, in my recent New Money Review article).

But in this article I want to focus on a kind of fraud that is at first glance less easy to understand. It involves creating a debit card at a financial institution with a fake ID and with no money in the account, at least at the outset.

Why would anyone wish to do this? Money laundering! Or sanctions evasion

Why would anyone wish to do this? Money laundering! Or sanctions evasion–you can choose how you want to call it.

In the current war, the only way for many people to make transactions in foreign currency in or from Russia (since it’s now almost impossible to store and move FX within the country) is to create such fake accounts. This is the reason why the demand for such services has recently spiked and will probably rise even further.

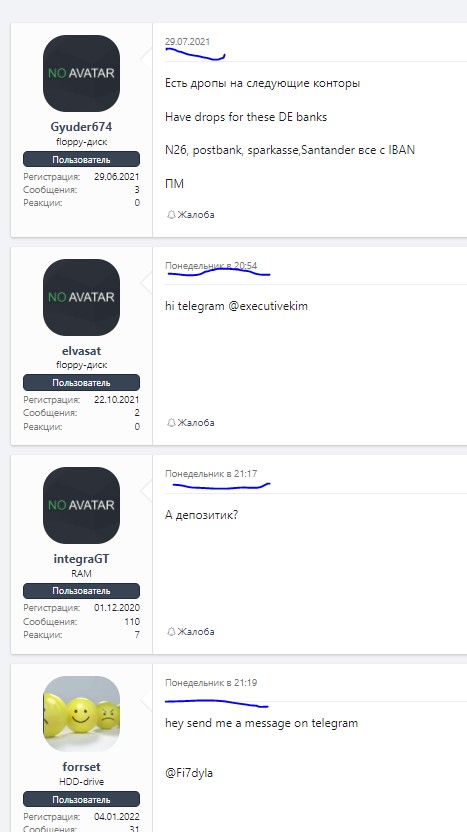

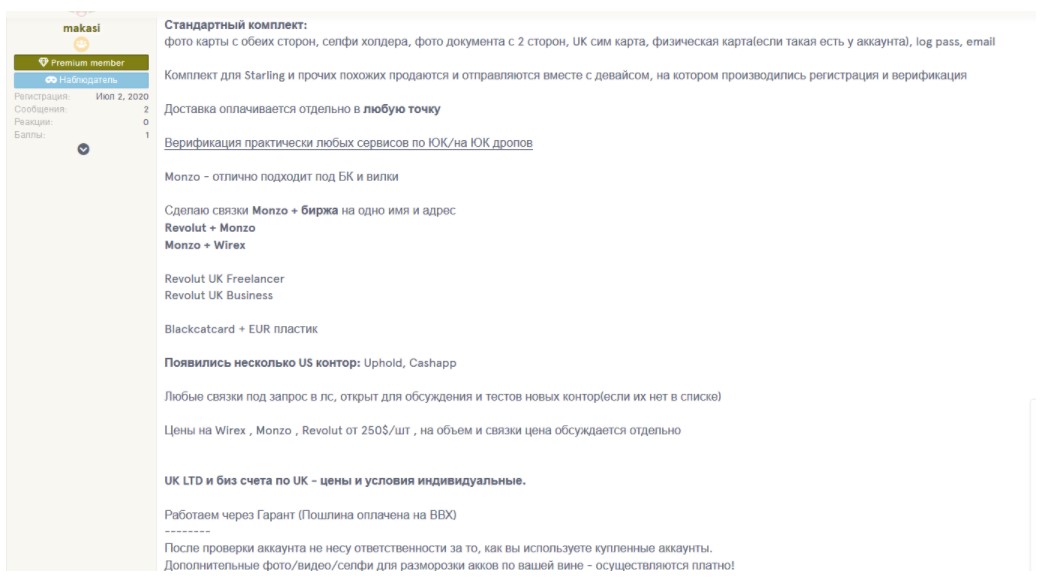

New demands for EU bank accounts

Ads on the Russian-language dark web promise to create fake IDs using any name you like. They sell cards based on those IDs, issued by a variety of well-known Western fintechs, including Monzo, Revolut, Starling, Blackcatcard, Uphold and Cashapp. The dark web sellers then promise to deliver the cards anywhere in the world.

This may seem like a small-scale fraud. But the two people recently charged in the US with attempting to launder the proceeds from the 2016 hack of nearly 120,000 bitcoin from cryptocurrency exchange Bitfinex apparently made use of such services. And while the US authorities have seized $4bn of the $5bn in stolen bitcoin, the remaining billion is still missing.

Ads on the Russian-language dark web promise to create fake IDs using any name you like

According to the indictment, Ilya Lichtenstein and Heather Morgan visited Kiev in 2019. While there, they apparently received packages from Russian darknet vendors. Those vendors offered to provide fake Ukrainian passports and mobile phone accounts, as well as debit cards issued to fake IDs.

So Lichtenstein and Morgan apparently laundered about 25,000 of the stolen bitcoin over the past five years, using various methods to cover their tracks, from fake IDs to converting the stolen coins into other digital currencies.

Offer of fake IDs on Russian dark web site

How do these dark web sellers–and their clients–get around financial institutions’ “know-your-customer” (KYC) and “anti-money-laundering” (AML) rules, which are supposed to ensure that only real, legitimate people can do business with them?

To better understand how this happens, we initially wanted to purchase these cards from the criminals. But it turned out this might cause legal actions against us. So instead of that, we found a fintech startup willing to add these checks to our fraud simulation offering.

Then I did an experiment. I faked a version of my own ID and tried to open accounts with it.

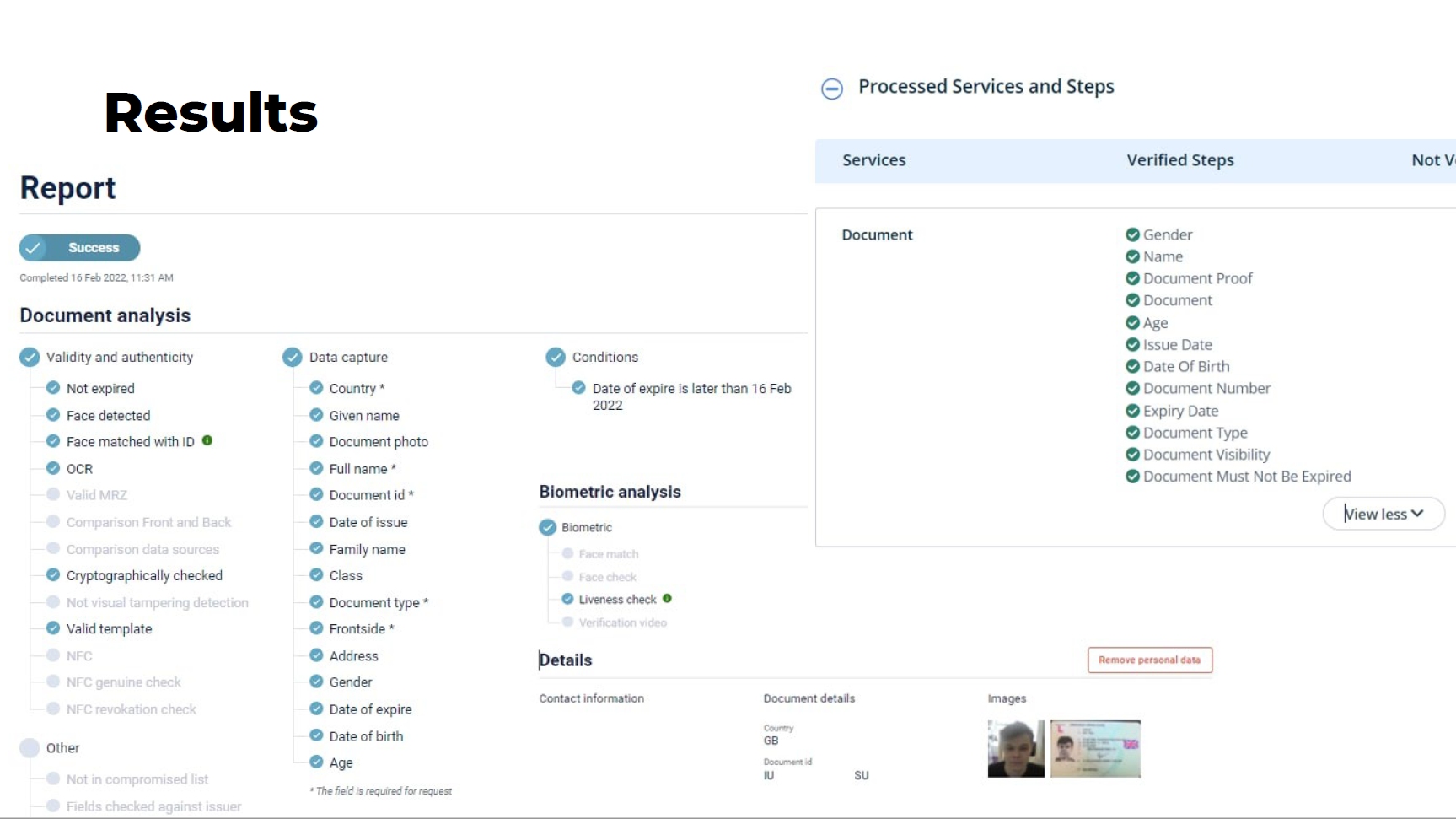

Before I tell you what happened, here are the most common KYC steps in the digital age.

First, a new client undergoes a liveliness check. This means the client’s image is supposed to be recorded via a live capture from the phone at the time of the account opening, not from past recordings or photos.

a new client undergoes a liveliness check

Second, the client’s key details, such as first name, last name and date of birth, are obtained via optical character recognition (OCR) from the ID document.

Third, the KYC provider’s staff and software ensure that no tampering of documents has taken place. Additionally, the client’s details are checked against blacklists.

Fourth, the KYC provider might consult social media accounts. If you have no presence on, say, Twitter, Instagram or Facebook, or if you opened your account yesterday, that’s a black mark.

Then there’s the principle of progressive KYC. If you want to transact in under, say, £100, the checks may be limited. If the amount is £100-£1000, you will need to show one form of ID, say a driving licence or passport. And if it’s more, you probably need another document, such as a proof of address.

How can fraudsters get round these rules? They can use photoshop to fake the IDs. They can get rid of any evidence of tampering. They can fake the plastic or the holograms used on the ID documents. And it’s quite useful to start with a database of stolen names and addresses. This means you’d be creating a fake ID based on another real person–without their knowledge.

So here’s what I did. Using photoshop, I took my real UK driving licence and doctored it to change my name. Specifically, I removed a few characters at the end of my first and last names, keeping the rest of the fields on the document unchanged.

Timur Iunusov becomes Timu Iunus

I couldn’t imagine that this would enable me to open an account at a fintech. But it did!

At the end of the fraud simulation exercises, I got an email saying my account had been blocked.

Worse, some time later, I got an email from one of the firms at which I had a real account, under my real name, saying I had been kicked out of their systems. Because of my attempt to open an account with a fake ID, I must have made it onto a blacklist–there are only a few KYC vendors out there.

These experiences might suggest that sometimes KYC systems are working as they should do, preventing bad actors from entering the system.

But by setting up trial accounts with KYC vendors and playing around with the inputs used for their checks (remember, I was doing this for clients who’d asked me to test their systems), I found I was able to bypass most of them.

For example, I used a rooted mobile phone to substitute the data used by the KYC vendor in the liveliness check.

I managed to bypass the KYC check with an edited image

I then used the virtual camera in a desktop computer’s browser to fool the KYC vendor into thinking that an image was being taken in real time.

KYC vendors check so-called EXIF meta-tags when verifying images. For example, these meta-tags specify the make and model of the phone, the date an image was altered and the GPS coordinates of the place the picture was taken. I deleted these tags, which in theory should have raised a red flag, but still got past KYC checks.

Finally, the XML tags associated with an image shows whether it’s been edited in Adobe or Photoshop. Signs of editing should again raise concerns, but I managed to bypass the KYC check with an edited image.

Timu Iunus gets the KYC go-ahead

What does this all tell us? It’s extremely easy to bypass KYC checks in the UK, Europe and especially so in the US, where so-called synthetic identity fraud is rife.

These fake accounts are the last mile for those seeking to extract laundered money from the system.

synthetic identity fraud is rife

How big a problem is this?

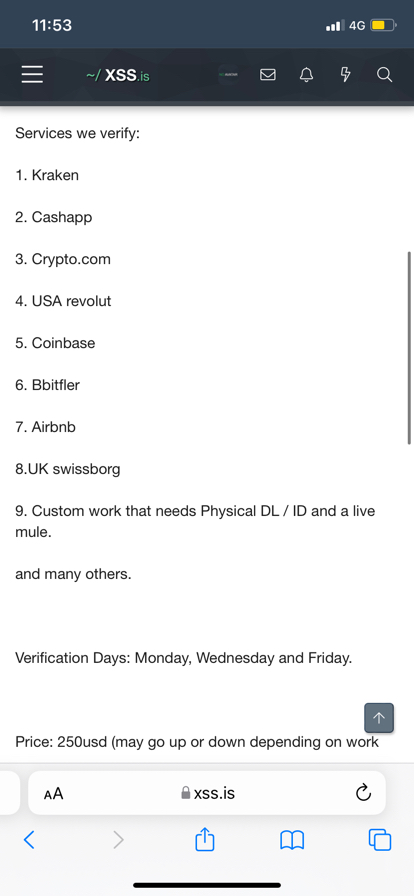

It’s hard to say exactly. But judging by a screenshot I took last week from a darknet vendor, offering for $250 to verify accounts based on fake IDs at a range of institutions, from cryptocurrency exchanges to Revolut and Airbnb, it’s still a real concern.

Fake ID accounts for sale last week

Financial institutions must not forget that criminals are most active in times of turmoil and uncertainty. A lot of campaigns for the financial support of Ukraine have already been abused by criminals.

Just imagine how easy it is to pretend to be a Ukrainian, using the techniques described above, and claim for $50 from a popular cryptocurrency platform?

FTX gives away $50 to each “Ukrainian user”

What can companies do? They can stop criminals gaining entry-level access to systems by demanding more rigorous KYC for even small amounts. For example, Samsung Pay+ does not require any documents until you spend your first £100.

You literally send your name and address using a Samsung phone and a card will be sent in a few days. Only when your transactions exceed £100 will they ask for more ID information.

the problem of fake IDs is not confined to individuals

Better detection of endpoint anomalies can help. For example, most of us enter our date of birth or social security number quickly on websites (since we remember them). If someone types in the information slowly or with pauses, that can be spotted by KYC/AML algorithms and the account made subject to additional checks. These examples were shared by Uri Rivner a few years ago.

And of course, sharing data and blacklists between different KYC providers (and between countries) can help root out money laundering and other financial crime. It’s ridiculous that the government in one European country can’t immediately verify if a citizen’s driving licence from another country is correct.

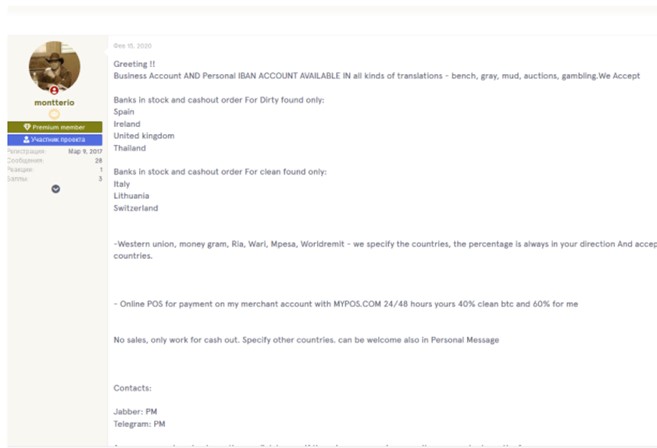

Of course, the problem of fake IDs is not confined to individuals. There’s a massive problem with companies laundering money. Nearly half the electronic money institutions (EMIs) set up in the UK have been flagged by a watchdog for financial crime risks.

Fake business accounts cost more, but the principle is the same

And money launderers must be laughing at the UK’s rules demanding disclosure of the true owners of companies, since fraudsters are so clearly breaching them without punishment. But that’s another story.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content from New Money Review

Kleptocratic money flows may kill democracy