The market at the centre of the world’s financial system—repo—is witnessing record popularity. But it’s always prone to collapse, and now cryptocurrencies are joining the fray.

The repo market

The repurchase (‘repo’) market is invisible to most people, but it plays a critical role in the global monetary system.

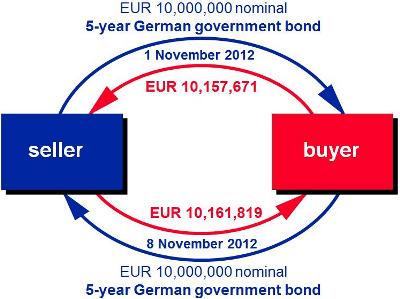

In a repo transaction, someone in need of cash takes an asset they own—say a bond—and sells it, but just for a short period, for example a day or a week.

At the end of that day or week they buy it back. They do that by returning the cash (plus a little interest) to the same counterparty.

To add a layer of security to the trade, if the original borrower fails to bring the cash—it might have gone bust in the interim—the temporary owner of the bond can sell it.

Repo lenders can jump the queue

The repo market is huge—US$13trn, by one estimate—and it got that big by acquiring special legal status.

Normally, when a bankruptcy occurs, a judge or administrator freezes the borrower’s assets and everyone has to wait months or years until the bankruptcy courts establish who gets what.

But repo lenders can jump the queue. They can sell their collateral immediately after a default, take all of their money back and move on to the next deal.

Some have been trying for a while to restrict that legal privilege, but without success. The repo market, and the interests it serves—including the government, corporations and the financial sector—is simply too big and powerful.

A one-week repo (illustration from ICMA)

Repo as a deposit

You can look at repo in a different way, this time from the perspective of someone looking to deploy cash, not raise it.

In the mirror image of the transaction described earlier, someone with surplus cash can temporarily buy an asset (usually a bond) before returning it later, earning interest in the interim. This deposit-like transaction is called ‘reverse repo’.

Money market funds now have a hot new competitor—stablecoins

If the asset concerned is a high-quality one (such as a US Treasury), you end up with one of the safest ways to park cash. It’s much less risky than placing the money on deposit at a bank, for example.

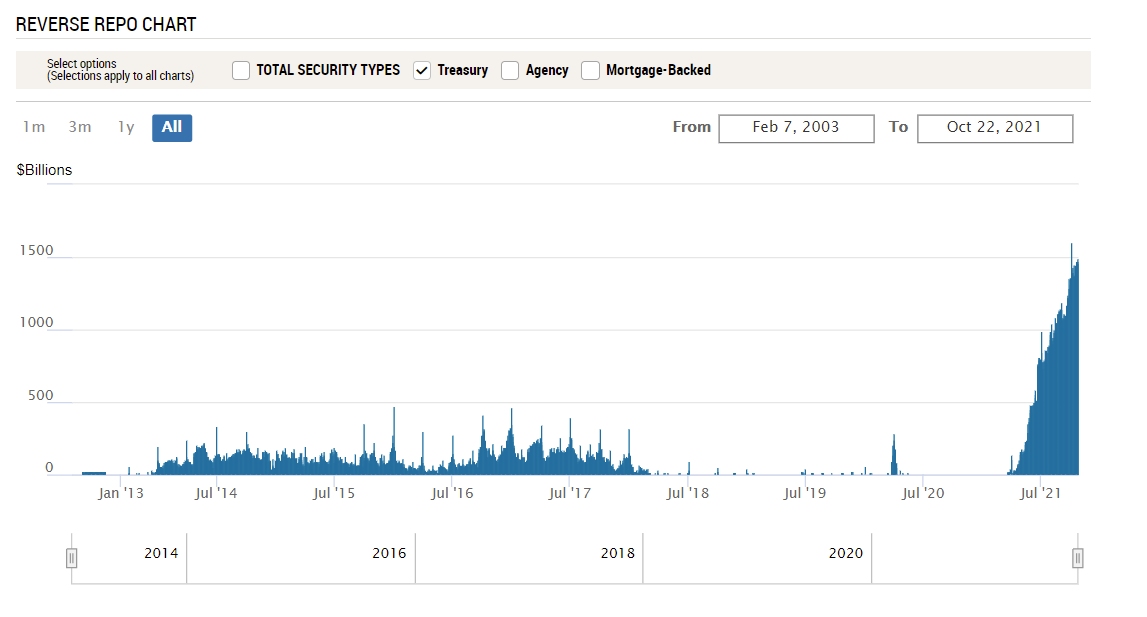

This particular use of the repo market has ballooned in recent months: at the end of September, cash-heavy investors had placed a colossal US$1.6trn into reverse repos with the US central bank, up from zero in March.

The Fed’s reverse repo facility

The Fed uses its reverse repo facility to underpin its policy interest rate.

Without the facility, many observers say, wholesale US interest rates would already have dipped below zero. Currently, the Fed pays 0.15 percent per annum on reserve balances.

Money market funds and stablecoins

Negative US interest rates would have hit one category of repo market participant particularly hard—money market funds (MMFs).

In many financial markets around the world, MMFs are the dominant savings vehicle for excess cash. They promise—more or less firmly—positive returns and the safety of the cash invested.

MMFs are also the principal suppliers of cash in the repo market. Receiving negative interest rates—that is, steadily eroding investors’ principal—would undermine their main selling point.

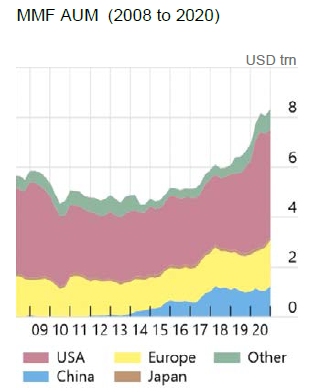

According to the G20 Financial Stability Board, the assets in global MMFs have doubled since the 2008 financial crisis, reaching $8.8trn at the end of 2020.

Money market fund assets worldwide

Money market funds now have a hot new competitor—stablecoins. These digital tokens, whose value is pegged to that of an existing fiat currency (like the dollar), carry a similar promise of capital preservation.

Stablecoins like Tether and Circle now have collective assets of over US$130bn, up fifteenfold in eighteen months.

MMF stresses

MMFs and stablecoins are often described as shadow banks. They provide some of the same services as banks—in this case, the deposit-taking function—without being regulated in the same way.

But just like banks, MMFs and stablecoins are exposed to runs, a particularly dangerous kind of financial panic.

In a run, a strain on one MMF may affect others that hold similar assets. Common structural features may cause investors to react to news about one fund by redeeming shares from others.

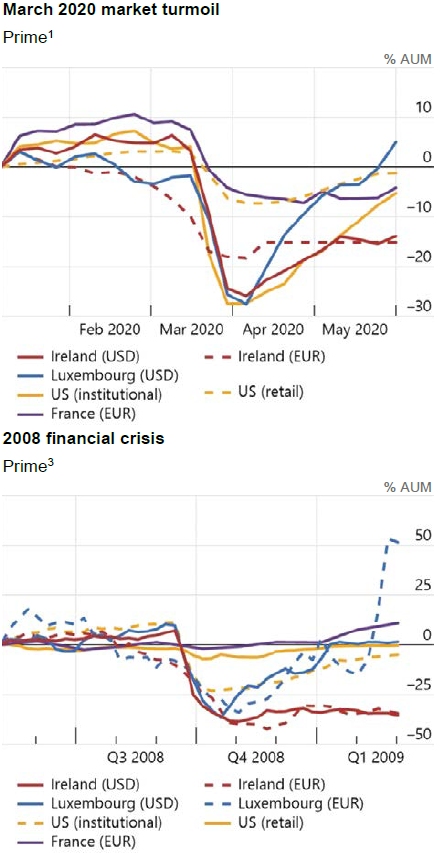

In 2008 there was a run on MMFs and the repo market seized up

And the financial market’s reliance on MMFs for cash management and as margin collateral threatens wider damage if an MMF gets into trouble.

In fact, MMFs and repo were at the heart of the 2008 market meltdown.

When the Reserve Primary Fund, a popular MMF, turned out in 2008 to have invested heavily in asset-backed commercial paper, a type of debt instrument whose value was exposed to the plummeting US property market, there was a run on MMFs and the repo market seized up.

The central bank swiftly intervened. Regulators, starting in the US, then moved to make MMFs safer.

In 2014, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) forced institutional MMFs to move to a floating, rather than a fixed net asset value per share, a reform intended to reduce run risk.

But another run on MMFs—and, thereby on the repo markets that underpin the system—happened again in 2020, during the market panic over coronavirus.

In both 2008 and 2020, the US central bank was forced to provide emergency support to the whole sector, underwriting trillions of dollars of liabilities.

Prime money market fund outflows in 2008 and 2020

Reining in repo

For those intent on reining repo, the usual place to start is by making MMFs less susceptible to a run. But that’s a tough challenge.

For a start, the global MMF sector is far from homogeneous. In China and Japan, MMF ownership is largely retail. In Europe it’s institutional and in the US it’s both. Some regions allow fixed-NAV MMFs, the riskiest type of fund, while others don’t.

the repo market’s risks are replicated and amplified in the free-for-all digital stablecoin markets

In different markets, regulators may set different thresholds for the ownership of less liquid underlying assets. Anti-run provisions, such as liquidity fees or redemption ‘gates’, are not applied evenly around the world.

Meanwhile, the potential contagion risks are rising.

In a consultation paper, released this summer, the G20 FSB warned of the growing reach of MMFs into less liquid areas of the short-term funding markets, like commercial paper (CP) and bank-issued certificates of deposit (CDs). Whereas you can normally unwind a repo early, in the CP market you can’t do anything until maturity.

All the repo market’s risks are replicated and amplified in the free-for-all digital stablecoin markets.

Stablecoin Tether, for example, showed in its end-June attestation report that nearly half of its $63bn assets were in CP and CDs. Unlike MMFs, which in many parts of the world publish their holdings daily, Tether and other stablecoin issuers refuse to do so.

Fundamentally unstable

According to an increasing number of observers, the global financial system’s reliance on repo is now a source of weakness rather than strength. The system is constantly at risk of failure, they say.

“By promoting instead of reforming the repurchase market, the Fed is trapped,” Mary Fricker, publisher of the Repowatch blog, said earlier this year.

The growing role of repo also means central banks are petrified to raise interest rates, for example during the recent inflation spike.

“It’s not even clear that the Fed can raise rates to cool an overheating economy any more, since rising rates will cause repo collateral to lose value, spurring repo lenders to demand more collateral or repayment, and that can lead to fire sales and a repeat of 2008,” Fricker said.

“The only thing that can solve the problem is absolutely massive central bank intervention”

Meanwhile, the expansion of repo to include non-government bond markets makes problems more likely to spread, says Mark Roe, a professor at Harvard Law School.

“The broad expansion of short-term repo, particularly repos of mortgage-backed securities, made major American financial firms more sensitive to financial shocks, more sensitive to disruption in the housing market, and more likely to propagate those shocks through the financial system,” he said.

Others point out that this instability also implies a constant drain on the public purse.

“The collateralised money market is just fundamentally unstable,” said Carolyn Sissoko, senior lecturer in economics at the University of the West of England.

“It’s essentially prone to liquidity spirals, where effectively, the only thing that can solve the problem is absolutely massive central bank intervention.”

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content from New Money Review

Crypto’s wildfire growth creates run risks