Governments should use their tax and spend powers to address rising levels of inequality, rather than relying on central banks to help build a fairer society.

That’s the message from the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), the policy-making body for the world’s central banks.

In a virtual lecture given on May 6 at Princeton University, the BIS’s general manager, Agustín Carsten, said that governments should aim to achieve a more equitable society through broader public policy measures, rather than relying on central banks to help reach this goal.

“Over the long run, inequality is not a monetary phenomenon,” Carstens said, “though central banks’ actions can have an impact on the distribution of wealth and income over shorter horizons.”

The measures central banks take to address high inflation or recessions, such as changes in interest rates, do affect the way a country’s assets and incomes are shared, he conceded.

But “the best contribution monetary policy can make to an equitable society is to try to keep the economy on an even keel by fulfilling its mandate,” Carstens said.

“Governments can reduce inequality through more direct fiscal and structural policies,” he said.

Central banks have been criticised for contributing to rising levels of inequality via their policies of near-zero interest rates and quantitative easing (QE), brought in immediately after the 2008 crisis.

Zero rates and QE benefit existing holders of financial assets disproportionately, say critics, exacerbating the wealth divide in society.

“Due to the asymmetric power of central banks, QE increases wealth inequality,” Martina Metzger of Berlin University and Brigitte Young of the University of Münster, said last year.

Such allegations have been fiercely resisted by individual central banks, who have produced their own studies to counter them.

“Inequality hasn’t risen—nor, according to the most detailed analysis available, did easier monetary policy have any net impact on it,” Ben Broadbent, deputy governor for monetary policy at the Bank of England, said in 2018.

In his speech at Princeton, the BIS general manager chose not to discuss the controversial topic of QE.

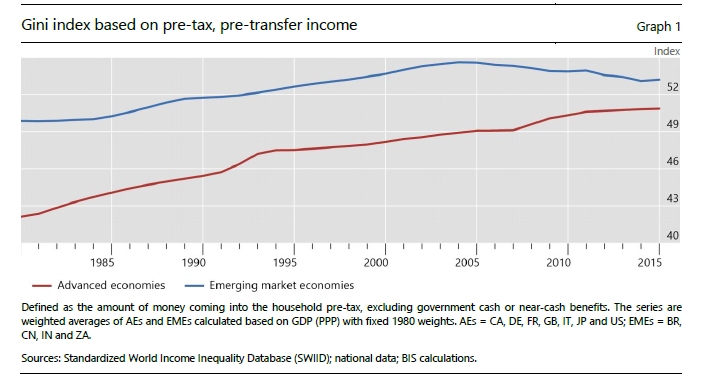

However, he conceded, inequality has been on the rise worldwide since the 1980s.

And it’s in advanced economies where the wealthy have been doing particularly well financially, said Carstens

Income inequality (Gini index) in advanced and developing economies

“The two main dimensions of economic inequality—income and wealth—have been on an upward trend,” said Carstens

“A concrete example is the case of the United States, where the share of income held by the top 1 percent of the population grew from 11 percent in 1986 to 19 percent in 2019,” Carstens said.

However, argued Carstens, rising inequality is largely the outcome of long-run structural forces, including technological change, globalisation and shifts in institutions.

“These forces are largely independent of and insensitive to monetary policy,” he said.

In fact, Carstens argued in his speech that allowing levels of inequality to rise further would weaken the ability of central banks to do their job.

“Inequality affects monetary policy decisions to the extent that it weakens the transmission of monetary policy,” he said.

“Households with relatively higher income and wealth typically have a lower tendency, or marginal propensity, to consume and tend to react less to changes in policy rates.”

As global economies recover from the damage wrought by the coronavirus pandemic, there are increasing signs of a shift in both monetary and fiscal policies in the US.

Earlier this week, Federal Reserve chairwoman Janet Yellen hinted at future dollar interest rate rises, while president Joe Biden said on Monday that tax increases for millionaires and corporations are fundamental to creating a fair economy that rewards work and grows the middle class.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes