As more details of the RobinHood crisis emerge, it has become clear that the stock-trading app at the centre of the busiest period of trading in Wall Street history was less a friend of the poor than a Moby Dick, a large carnivore with retail gamblers as its prey.

Founded in 2013 by two Stanford graduates, RobinHood, which sells itself as offering everyone—not just the wealthy—access to the financial markets, has gone from start-up to market whale in the space of a few years.

On January 27, the firm found itself caught up in the busiest day in US stock market history, with 23.3bn shares traded, nearly 20 percent more than on 10 October 2008, in the depths of the great financial crisis.

Musk incites trading frenzy

At the centre of the trading frenzy was a previously obscure electronics and video game retailer called GameStop.

Coordinating their actions on social media app Reddit, millions of retail traders bought GameStop shares in an attempt to take revenge on what they saw as a nefarious group of Wall Street actors—short sellers attempting to benefit from the company’s demise.

The Reddit message board members were acting not just of their own volition.

A day earlier, Tesla chief executive Elon Musk had helped launch the assault on short sellers by tweeting ‘Gamestonk’, a coded message to the retail traders that they should push up GameStop shares (stonk is a deliberate misspelling of ‘stock’, associated with a meme popular on social media).

In 2019, Musk reached a deal with the US securities regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which had accused him of securities fraud after Musk tweeted he had secured funding to take Tesla private at $420 a share, a substantial premium to its market price at the time. The Tesla boss later conceded he had not arranged financing for the transaction before tweeting.

As part of the deal, Musk promised not to tweet market-sensitive information about Tesla in future without first consulting the company’s lawyers.

But the regulator’s rap across the knuckles hasn’t put the world’s richest man off using social media to incite other market moves: in the last two weeks, Musk-issued tweets have sparked large upwards price moves in cryptocurrencies bitcoin and dogecoin, as well as in GameStop.

“You’ve been gamified”

According to Michael Burry, one of the central characters of ‘the Big Short’, the 2015 film about the sub-prime mortgage crisis, RobinHood symbolises the ‘gamification’ of finance, with retail traders the unwitting victims of much bigger market players.

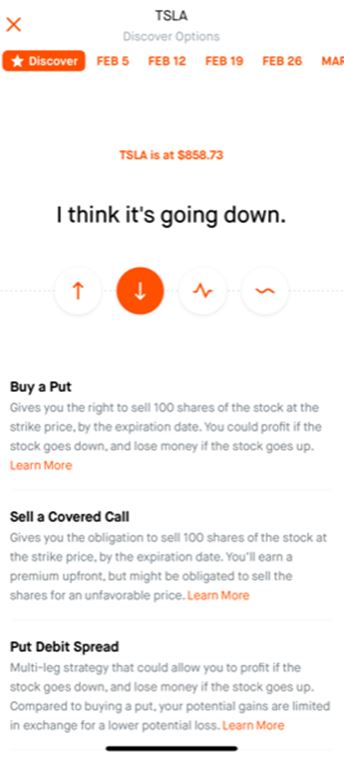

“If you do not use #robinhood, you have to see it to understand what [the] #gamification of #stonks/options means,” Burry tweeted on February 4.

“So here it is. If this looks like a serious investing app to you, and NOT a dangerous casino ‘fun for all ages’, you’ve been #gamified,” wrote Burry, posting an image of a sell screen from the RobinHood app. On the screen, app users are encouraged to ‘discover options’ to place bets on the Tesla share price going down.

Last summer, one 20-year-old US student committed suicide after believing he had incurred over $700,000 of losses in options trading using RobinHood. The student, Alexander Kearns, had no income and was living with his parent in Illinois.

Options trading screen on RobinHood app

If it’s free, you’re the product

The promise to trade stocks and options free of commissions has been a major lure for many RobinHood clients. But according to many market analysts, the no-fee claim helps obscure the app’s main source of income—kickbacks from professional trading firms.

In December, RobinHood paid a $65m fine to the SEC, after the regulator said it had misled its customers about how it was remunerated by Wall Street firms for funnelling customer trades to them, in a practice called ‘payment for order flow’.

The SEC also said the start-up had made money at the expense of its customers. Robinhood agreed to pay the fine to settle the charges, without admitting or denying guilt.

Reverse-engineering the market

According to Paul Rowady, director of research at consultancy Alphacution, which specialises in analysing the structure of US equity markets, information about RobinHood clients’ orders has proved especially valuable for the biggest high-frequency trading (HFT) firms.

“Most amateur traders are taught to use stop-loss orders to do precisely what they say they are supposed to do: limit losses,” Rowady wrote last year.

“For traders that aren’t able to watch their risks all day long, stop-loss orders represent one tool by which part-time traders – like those who have other day jobs – can put their trades on autopilot. Moreover, in a zero-commission environment, there is no explicit cost to the trader if a trade gets stopped out. That trader can always get back into the trade, at no explicit cost.”

“Stop-loss orders – and other variants, like trailing stop-loss orders – are quite valuable. This category of orders is otherwise known as non-marketable limit orders (NMLOs), and they are the type of order that high-speed market makers covet more than any other.”

Rowady calculated that such remuneration by high-speed traders for such limit orders represented more than two-thirds of the payments received by retail brokers like RobinHood during the first quarter of last year.

For 2020 as a whole, RobinHood alone made over $600m from market makers as a reward for providing order information from its retail clients. According to the Financial Times, Wall Street trading firms paid almost $3bn last year for information on retail orders.

In an email exchange with New Money Review, Rowady explained how market makers exploit the information they receive in the form of limit orders.

“Wholesale market-makers and other ‘hyperactive strategy’ firms (HFT), have reverse-engineered a very accurate picture of the market—measured in nanosecond increments—using various data feeds that helps them draw that multi-dimensional picture,” Rowady said.

“They know what orders and liquidity live around the national best bid and offer (NBBO) —and the demographics of that order flow—at each sliver of time, and therefore, able to quickly identify arbitrage opportunities between and among a complex and fragmented array of liquidity venues, both lit and dark,” Rowady said.

Citadel, one of the high-frequency trading firms paying RobinHood for its retail order information, remains highly profitable, according to one expert in the US equity market’s trading structure.

“It was floated around that Citadel Securities generated $6.7bn last year. I would say, this year isn’t starting off on the wrong foot.” Larry Tabb, head of market structure research at Bloomberg Intelligence, said on Twitter yesterday.

More small fry in the food chain

By February 5, GameStop shares were priced at $63, an 87 percent decline from a January 28 peak of $483.

For retail investors who placed their trades during the late-January price run-up and are now out of pocket, the last two weeks might be seen as a reminder that gambling is dangerous and the house always wins.

But if that’s the message, many retail punters aren’t listening. Instead, there’s an even bigger queue of small fry willing to enter the financial market food chain at the bottom.

RobinHood saw more than 600,000 people download its app last Friday, more than four times its previous daily record, set during the Covid-19 market panic of last March.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes