Too strict a reserve policy makes asset-backed money of limited use. But too lax a policy may be the first step on a slippery path to destruction.

Since US President Nixon ended the convertibility of the dollar into gold in 1971, we’ve been living through a 50-year experiment with ‘fiat’ money—money backed by nothing except the say-so of the state issuing it.

Perhaps in reaction, in recent years there’s been rapidly rising interest in the idea of asset-backed money—money supported by a reserve of something else (such as gold, silver or even other fiat money).

Digital asset-backed money units are often called ‘stablecoins’—a term invented to distinguish this type of money from volatile cryptocurrencies like bitcoin.

Stable money is useful: unlike bitcoin, for example, you’d want to use a stablecoin for payment, or to price your goods and services.

But designers of asset-backed money face a difficult choice: do they insist that the reserve backing is 100 percent at all times, or do they allow some flexibility in the backing ratio? This apparently technical detail proves to be a surprisingly important one.

Lessons from Amsterdam

In a working paper they released last week, three economists at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Jon Frost, Hyun Song Shin and Peter Wierts, draw on the history of the Bank of Amsterdam, the dominant financial institution of the 17th and 18th centuries, to illustrate the point.

According to Frost, Shin and Wierts, the Bank of Amsterdam initially made some sensible changes in its money’s design, allowing for some credit within the system while keeping the gold and silver backing largely intact.

But over time, under political pressure and seduced by potential monetary gains, the Bank of Amsterdam’s managers started backing their money by risky debt rather than gold and silver.

“In the late 1770s, under the economic pressures generated by a new war with the English, the Bank embarked on a period of more serious divergence from its charter by lending on a more substantial scale, in a sustained and non-transparent way,” Frost, Shin and Wierts write in their paper.

By 1820, the market value of Bank of Amsterdam money had plummeted and the bank was closed. Its stablecoin experiment had failed.

Demand for credit is not stable

It might seem sensible for an asset-backed money system to have 100 percent reserve cover at all times—or even more.

Modern currency board systems, such as those in Hong Kong and Bulgaria, indeed follow this principle.

They maintain a stable exchange rate to an anchor currency—in Hong Kong’s case, the US dollar and in Bulgaria’s, the euro—by maintaining backing assets that are larger than the amount of money in circulation.

But such a rigid approach limits the usefulness of asset-backed money as a settlement instrument, say Frost, Shin and Wierts.

a rigid approach limits the usefulness of asset-backed money

Why? The authors use the 18th century activities of the Dutch East India company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or ‘VOC’), the dominant global trading firm of its time and the prototype for modern corporations, to explain.

They argue that, had the Bank of Amsterdam’s monetary system not had some in-built flexibility, it would have been unable to serve its largest client, the VOC, which was involved in much of the global trade of the time.

The Bank was also the centre of an increasingly important, interconnected web of international credit relationships, the BIS economists say.

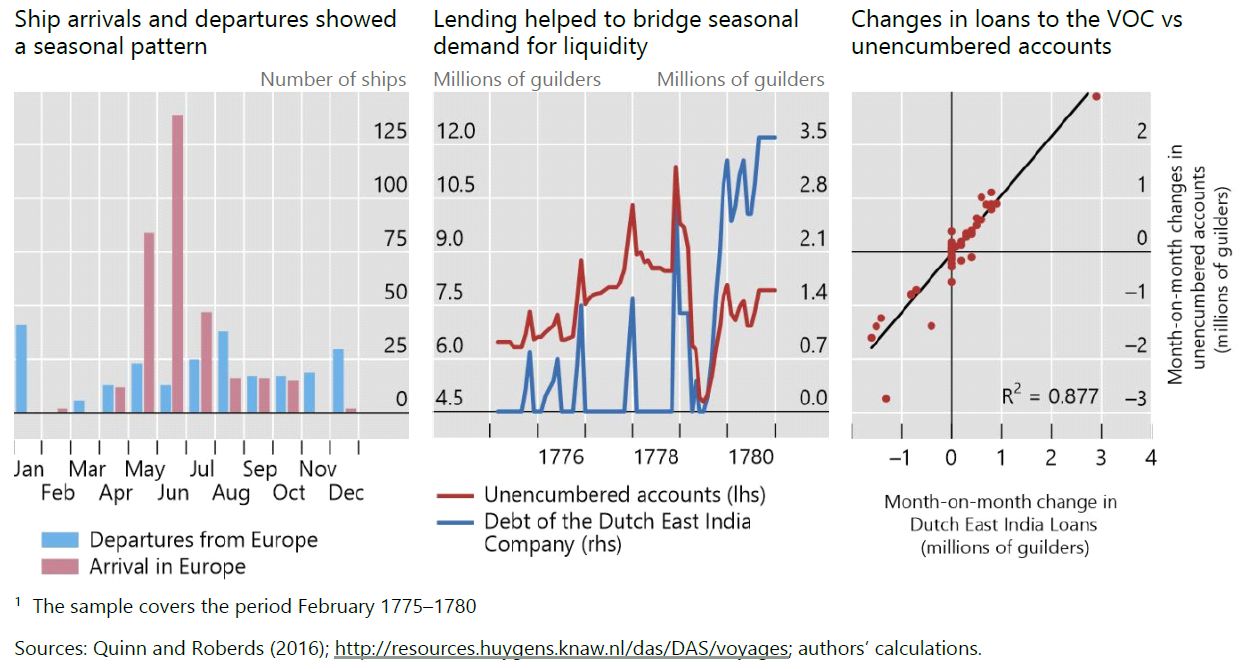

“Typically, [VOC] ships would arrive in Europe between May and July, and then would be kitted out for their outward journey in August to January,” Frost, Shin and Wierts write in the paper.

The trading company’s ships, which had to round the Cape of Good hope to travel between Europe and Asia, needed to avoid the stormiest times of year to make their voyages.

“The VOC faced a seasonal pattern in its financing need for working capital purposes, where its demand for credit peaked in the winter months, after ships had departed but before the arrival of goods to sell from Asia, Oceania and Africa,” say Frost, Shin and Wierts.

The resulting, ‘saw-tooth’ pattern of borrowing by the VOC is visible in a chart published in the BIS paper.

The Dutch East India company’s seasonal demand for credit

The Bank of Amsterdam met the VOC’s demands for short-term credit by increasing the trading firm’s ‘unencumbered’ accounts at the Bank.

At the outset, following the Bank of Amsterdam’s creation in 1609, depositors had the right to turn up at its doors and ask for their deposits to be paid out in gold and silver.

But if you had an unencumbered account, you couldn’t do this—you only had a contractual right to the amount of precious metal you owned.

Why settlement liquidity matters

Settlement liquidity, say Frost, Shin and Wierts, means the ability to execute payments promptly. In turn, this allows others in the payments system to fulfil their obligations.

But, they go on, preventing temporary overdrafts in settlement accounts would detract from the ability of money to serve one of its principal functions—as a means of payment.

“settlement liquidity emerges as a key source of potential inefficiency”

The problem is particularly acute when the payment system in question handles huge volumes of transactions.

“For modern large-value payment systems that transact in real time—so-called real-time gross settlement (RTGS) systems—imposing a cash-in-advance requirement can impose inefficient delays and possible ‘gridlocks’ in payments,” Frost, Shin and Wierts say.

As a result, “settlement liquidity emerges as a key source of potential inefficiency” in payments systems, say Frost, Shin and Wierts.

A question of trust

Ultimately, the durability of a monetary system comes down to a question of trust.

It was a test the Bank of Amsterdam initially passed—observers in other countries, like Adam Smith and Voltaire, were huge admirers of the Bank during the 18th century—but then failed.

In fact, by lending money outright to the Dutch East India company, the Bank’s managers were already breaching its founding charter, say Frost, Shin and Wierts.

Nor was the lending disclosed—a critical lapse in communication between insiders and the general public and one reminiscent of many later market scandals.

As we witness an increasing number of private stablecoin experiments—from Tether to JP Morgan coin, Fnality, Libra and Dai—the lessons of the Bank of Amsterdam have never been more relevant, say Frost, Shin and Wierts.

For the designers of these stablecoins, there’s one critical trade-off to consider, they say. And there’s no right or wrong answer.

If stablecoin managers stick to their governance rules, say Frost, Shin and Wierts, for example by insisting on full backing for the stablecoins at all times, their money will have limited use in facilitating payments for others.

But if they don’t stick to the rules, they may be enticed to expand their lending over time, causing the failure of the system as a whole.

“a vivid lesson in how a central bank that loses public trust can push its luck too far”

Central banks’ balance sheets balloon in size in 2020

While Frost, Shin and Wierts argue for the critical role of the central bank in addressing payments imbalances, they also fire a warning at public sector providers of money.

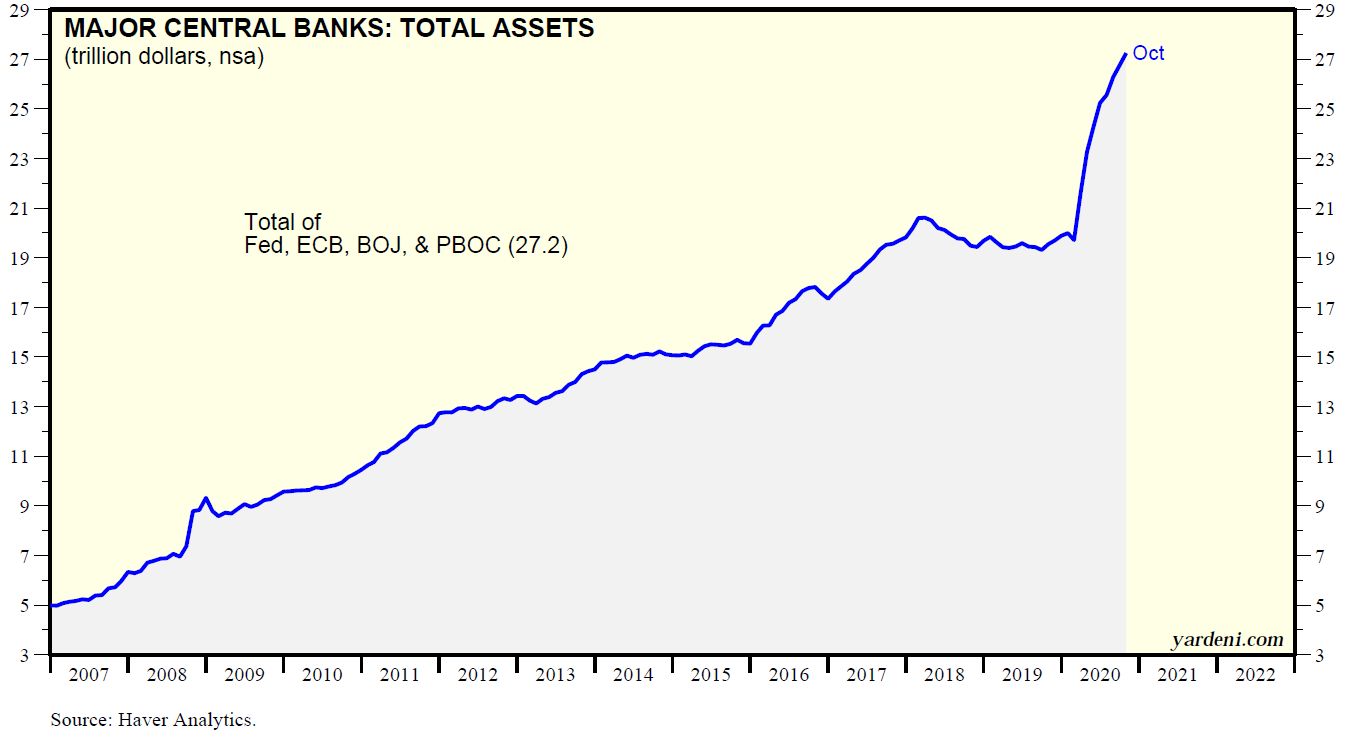

According to Yardeni Research, the world’s major central banks have inflated their collective balance sheets from $19trn to over $27trn in less than a year, reflecting the efforts to offset the economic impact of coronavirus.

“The Bank of Amsterdam’s failure is a vivid lesson in how a central bank that loses public trust can push its luck too far, beyond the threshold for failure,” Frost, Shin and Wierts say.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes