Privately issued stablecoins—digital money backed by fiat currency like the US dollar—won’t work in the long term as they lack the government support implicit in central bank money, say researchers at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

The BIS is owned by 63 central banks, representing countries that account for 95 percent of the world’s economic output.

In a new working paper, Jon Frost, Hyun Song Shin and Peter Wierts of the BIS compare a four-century-old ‘stablecoin’—money issued by the Bank of Amsterdam between 1609 and 1820—with its modern-day equivalents or prototypes, such as Tether, JP Morgan’s JPMCoin and Facebook’s Libra.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Amsterdam was Europe’s pre-eminent financial centre and the Bank of Amsterdam played a central role in global trade, in particular between the Spanish colonies of the New World and the growing markets in Asia.

Over time, the Bank of Amsterdam departed from its promise of strict reserve backing

In 1609, the Bank got off to a successful—and risk-averse—start. At the outset, Bank of Amsterdam guilders were fully backed by gold and silver deposits from clients and the bank had no right to lend out client money.

The BIS describes this policy, in modern-day terms, as equivalent to managing a ‘rigid stablecoin’.

But over time, say Frost, Shin and Wierts, the Bank of Amsterdam departed from the promise of strict reserve backing for its money.

Initially, say the researchers, the Bank offered temporary overdrafts to its clients to help address seasonal credit market tensions and to smooth the settlement of payments.

During this period of its history, the Bank of Amsterdam was operating a more ‘elastic’ stablecoin policy, the BIS researchers say.

However, in 1683 the Bank stopped its promise of redeeming client deposits for the equivalent amount of gold and silver bullion.

Instead, it introduced a system of depositary receipts, where owners of gold and silver coins could sell them to the Bank with an option to repurchase them later, subject to a small fee.

By the late-eighteenth century a series of wars and economic downturns had taken its toll on the Bank of Amsterdam’s governance, and on the security of its money.

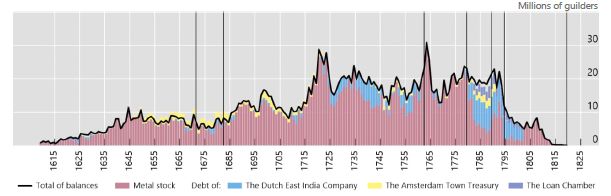

Over time, the Bank had started backing its money by much riskier assets than gold and silver. The new, less secure reserve base included debt from the Dutch East India Company and local municipalities, while the Bank also failed to warn depositors of its loosening credit policy, say Frost, Shin and Wierts.

Eventually, the market value of its money plummeted and by 1820 the Bank of Amsterdam was closed. Instead, the modern Dutch central bank—De Nederlandsche Bank—took over many of its functions.

Bank of Amsterdam assets 1609-1820

Source: BIS

In their working paper, Frost, Shin and Wierts say the history of the Bank of Amsterdam provides valuable lessons for today’s designers of asset-backed digital money, particularly when it comes to reserve policy and governance.

“The economic concepts of stablecoins and of central bank solvency are not new”

“The economic concepts of stablecoins and of central bank solvency are not new,” say the BIS researchers.

“The Bank of Amsterdam provides a rich source of experience on the working of money backed by assets, and the corrosive effect of excessive discretionary credit amid weak governance on the stability of this system,” they say.

“As a range of new private stablecoins are proposed for wholesale and retail use, there is the potential that the same limitations of rigid stablecoins, and conflicts of interest around elastic stablecoins, may arise,” the authors go on.

A better idea, say the researchers, is digital currency issued and managed by the world’s central banks.

“While [private] digital stablecoins could play a constructive role in certain specific use cases, it seems unlikely that they can fulfil the full range of functions of money,” say Frost, Shin and Wierts.

“For this, discretionary credit and appropriate fiscal backing will be needed. Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), which build on the existing governance of central bank money, are better placed to fill this gap,” they write in the working paper.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes