Cryptocurrency networks help support a growing volume of dollar transfers taking place outside the traditional financial system.

The growth of private stablecoins

As central banks around the world debate whether to introduce new digital versions of their national currencies, private sector firms are filling the gap, supplying digital money at an accelerating pace.

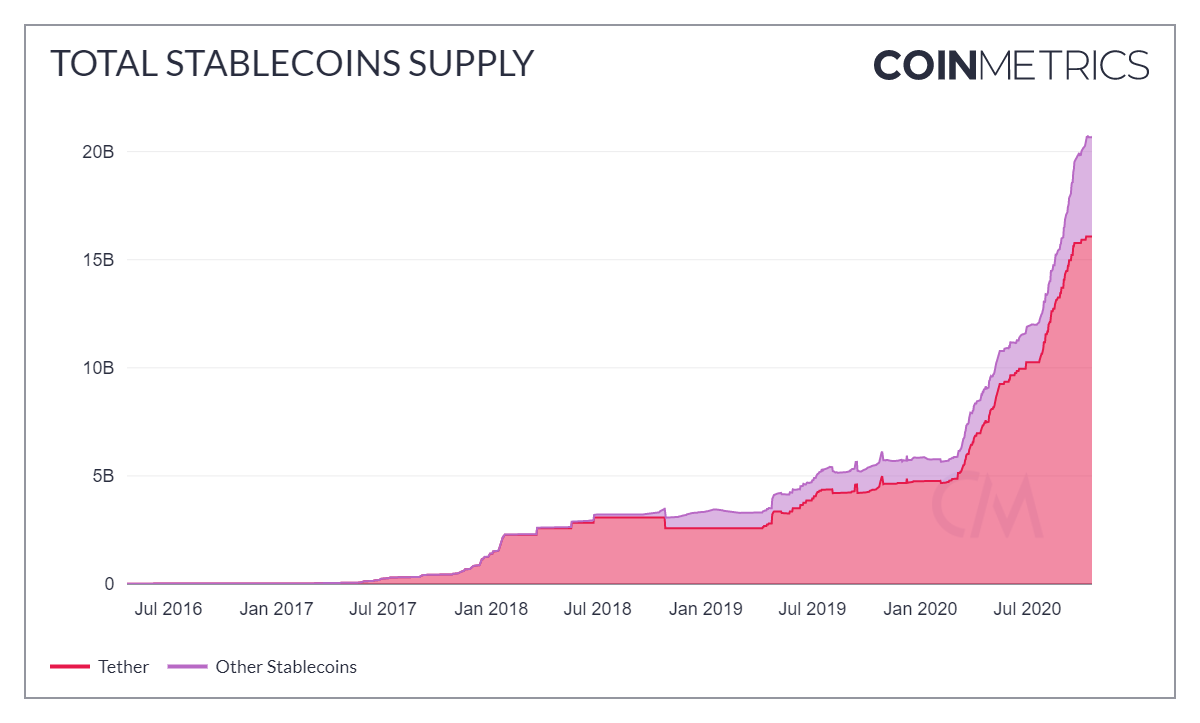

The total supply of stablecoins in issue has nearly quadrupled this year, from $5.8bn to $20.7bn, according to Coinmetrics.

Stablecoins are privately issued cryptocurrencies, which aim to track the value of traditional fiat currencies like the US dollar.

By contrast with dollars held in bank accounts, which have to be routed via the traditional financial system, stablecoins can be transferred directly from one consumer to another.

Tether, the most widely used stablecoin, has a controversial history. Its dollar reserve backing has been questioned, its supply has never been audited and its operators are battling a number of lawsuits, including one from the New York state attorney general.

The total supply of stablecoins in issue has nearly quadrupled this year

But tether’s supply has risen from under $3bn in April 2019, when the US authorities first unveiled their case, to $16bn today.

“As the most stable and liquid stablecoin, tether is proving itself to be one of the most trusted cryptocurrencies,” Tether, the company that issues the stablecoin, said last week.

“Our team is also working to further growth into online commerce and traditional finance.”

Tether says its unique selling point is that users can send and receive quasi-dollar tokens peer-to-peer, globally, instantly, and securely for a fraction of the cost of alternatives.

By comparison, transfers of dollars through the traditional financial system are available only to those with bank accounts, are costly and can take days to clear.

Using the standard money rails also leaves leave dollar users at the mercy of the US monetary authorities, who in the past have proved quick to sanction those they perceive as threatening the country’s national interests.

From eurodollar to cryptodollar

One of tether’s earliest use cases was to enable arbitrage between cryptocurrency exchanges, at a time when the price of bitcoin in different countries could vary widely.

Many of those exchanges had no banking relationships, preventing traders from conducting arbitrage by means of bank transfers from one fiat currency to another.

But according to Coinmetrics’ co-founder, Nic Carter, stablecoins like tether are now being used more widely.

“Stablecoins were created as a way to create stable collateral for traders within the crypto ecosystem,” Carter said during a recent interview.

“But we think there’s a much broader phenomenon occurring here, which is the injection of fiat currency into public blockchains and allowing these representations of dollars and bank accounts to circulate on public blockchains and to settle on them.”

“We think there’s a much broader phenomenon occurring here”

Carter said he prefers to call stablecoins ‘cryptodollars’, likening these new fiat currency tokens to a disruptive monetary technology of six decades ago—eurodollars.

In the late 1950s, the Soviet Union decided to transfer its dollar deposits from New York banks to banks in Paris and London, fearing confiscation by the US government after the 1956 invasion of Hungary.

The first dollar transfer made by the USSR to an account outside the US was to the Banque Commerciale pour l’Europe du Nord in Paris, whose telegraphic address was ‘Eurobank’.

The idea took off and in time, any dollar deposit held in Europe became known as a ‘eurodollar’ deposit.

The eurodollar sector took off not just because of geopolitics. Regulatory arbitrage had an important role to play in its success.

Banks holding eurodollars on deposit were not subject to US regulatory reserve requirements and they could pay higher interest rates to clients.

By contrast, US banks were limited in how much they could pay on domestic dollar deposits: under ‘Regulation Q’, they could offer maximum interest rates of 1 percent for one-month deposits and 2.5 percent for three-month deposits.

The growing pool of eurodollars in London, Paris and Zurich then helped spawn a long-term lending and borrowing market—called eurobonds. The first eurobond arrived in 1963 in the form of a $15m debt issue by Autostrade, Italy’s motorway builder.

Over the following half century, eurobonds grew into the world’s largest international capital market, playing a pivotal role in global fundraising and savings portfolios.

Scope for disruption

It may seem far-fetched to suggest that money transfers made using unregulated digital tokens could ever disrupt those made across the banking system.

“There are new payments and settlement rails being built out”

Despite the recent increase in supply, the total value of cryptodollars (at $20bn) is dwarfed by the $15.7trn of US dollar commercial bank deposits.

But according to Coinmetrics’ Carter, it’s important not to underestimate the significance of the cryptodollar phenomenon.

“It’s our view that there are new payments and settlement rails being built out,” he said.

“A really big part of that is the transmission of dollar-denominated assets on these rails.”

“So it’s not just the transmission of things like bitcoin and ethereum, which you could call ‘crypto-native’ assets, but the settlement and transmission of dollar-denominated assets which might be backed by dollars in bank accounts somewhere.”

“In my opinion the most dynamic and exciting thing happening right now is the growth of cryptodollars.”

Sign up here for the monthly New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes