The Bank of England governor gets it wrong about a possible return to ‘Wild West’ banking, according to George Selgin, a professor of economics at the University of Georgia.

Last week the UK’s central bank head, Andrew Bailey, warned of the risks caused by a proliferation of private currencies as a result of the growing number of ‘stablecoin’ initiatives.

Stablecoins are digital currencies backed one-for-one by reserves held in the respective underlying fiat (state-issued) currencies.

In a recent speech to the Brookings Institution, Bailey said that only the payment protections offered by governments and central banks, such as a lender of last resort function and state-provided deposit insurance, could ensure that consumers’ money will work as intended.

Bailey said that without these protections, we could return to a banking ‘Wild West’, in which individual banks or private sector entities issue their own currencies, worth different amounts depending on recipients’ assessment of the soundness of the issuer.

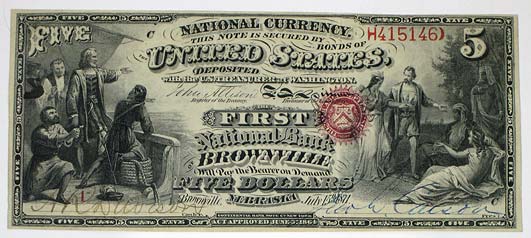

During the so-called Wildcat banking era, which lasted from 1836 to 1863 in the United States, banks were chartered under state law rather than being federally regulated.

As a result, banknotes issued by different banks traded at different discounts to their face value, and money users relied on published lists of banknotes to identify and value their holdings.

A Wildcat era banknote

However, according to Selgin, it was not the absence of regulation that caused Wildcat banking era notes to trade at different secondary market values, but the uneven state regulatory framework to which banks were subjected.

“With all due respect to Mr. Bailey, [his] statements are demonstrably false”

“With all due respect to Mr. Bailey, [his] statements are demonstrably false,” Selgin said on Twitter.

“There have been dozens of cases of private banking systems without central banks or deposit insurance, and many competing brands of private banknotes, where the notes circulated at par (face value) nationwide,” Selgin said.

“Mr. Bailey ought at least to have known about the famous Scottish system,” Selgin went on.

“Numerous Scottish banks issued notes denominated in pound sterling units, that the Scottish people even preferred to either Bank of England notes or gold itself, back when all were claims to gold.”

According to the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), the popularity of Scottish banks’ private banknotes reflects the past reliability of their issuers.

“Centuries ago, almost all of Britain’s banks issued their own notes—it was a key part of banking business,” RBS says on its website.

“Mr. Bailey ought at least to have known about the famous Scottish system”

“However, irresponsible note issuing could cause problems for the economy, so in the 1840s the government changed the law to encourage the gradual ending of English and Welsh banks’ notes, leaving just the Bank of England as an issuer,” RBS said.

“But in Scotland, the banks had been good at regulating and organising their note issues. The system was very stable, and people depended on it. The banks and the public together persuaded the government that the Scottish system didn’t need fixing, so the same controls were not applied to Scotland,” RBS said.

According to Selgin, there are other past instances of privately issued currencies trading at their face value.

“Another great example was Canada’s pre-World War One banking and currency system,” Selgin said.

“Same US gold dollar, no central bank, no serious banking crises, currency fully uniform by the early 1890s.”

According to Selgin, the main reason for the proliferation of discounts on US state bank notes during the pre-Civil war period was not the fact that they were issued by private entities without central government promises of support, but the uneven regulations imposed by the states in which those banks were registered.

“State regulators often required banks to buy bonds”

“So-called ‘free’ banks couldn’t have any branches,” Selgin said on Twitter.

“And they had to back their notes with securities specified by state regulatory authorities. These regulatory provisions account both for the discounts on ‘free’ bank notes and most free bank failures.”

“State regulators often required banks to buy bonds, including those of state or local governments, that turned into junk. That was the main case of [bank] failures,” Selgin said.

Selgin, who is also director of the Cato Institute’s Centre for Monetary and Financial Alternatives and a long-standing supporter of non-state money, said that the private sector itself has in the past helped organise mechanisms to ensure that individual banks’ notes are exchangeable on a one-for-one basis, at face value.

He cited Canada’s late 19th century banking market as an example.

“It was by letting its banks branch nationwide, and allowing them to set-up regional clearinghouses, that Canada achieved a uniform currency consisting of many banknote brands over an area as large as the US, and more sparsely populated,” Selgin said.

The Georgia University professor accused the UK central bank head of inadequate knowledge of money’s past.

“Like all too many people who do not know enough monetary history to avoid being dangerous, Mr. Bailey imagines that the so-called ‘free banking’ systems of the antebellum typify what happens when you let bankers loose in a setting without heavy regulation,” Selgin said.

Sign up here for our monthly newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes