Long-vilified for their environmental footprint, cryptocurrencies like bitcoin offer a potential solution to the growing problem of excess renewable energy.

Blackouts in the golden state

In the midst of last month’s heat-wave, California suffered its first rolling energy blackouts for 19 years, leaving homes and businesses without power for hours over a period of several consecutive days.

Press reports blamed the blackouts on a combination of reasons: heavy air conditioning usage, the unplanned unavailability of some power plants, and restrictions on the import of power from neighbouring states.

Whatever the cause, electricity blackouts simply demonstrate that grid designers have failed to match demand with supply.

“The power system is like a swimming pool. For the system to be stable, you have to produce exactly the same amount of electricity as the amount being consumed. Otherwise the system is unstable and you can have a blackout very easily,” Alejandro Hernández, a senior energy analyst at the International Energy Agency (IEA), told New Money Review.

Too much of a good thing

But the most likely cause of the California blackouts is a highly uncomfortable one, given the global alarm over climate change and greenhouse gas emissions.

The state is now suffering from too much of a good thing: excess renewable energy, in the form of solar power, has destabilised California’s system and made it difficult to manage.

the most likely cause of the California blackouts is a highly uncomfortable one

Unsurprisingly, in one of the sunniest regions of the world, solar energy floods the power grid in the middle of the day and then drops off abruptly at dusk.

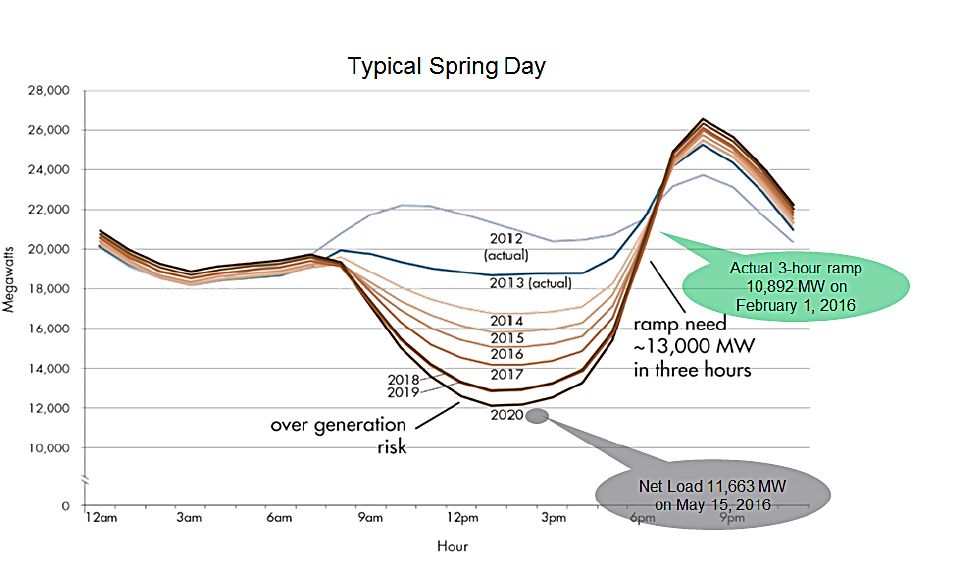

California’s power grid operator, the ISO, is well aware of the problem, and even has a special name for the midday glut and evening contraction in energy supply—the duck curve.

California’s duck curve

In a recent publication, the California ISO showed that the duck curve has been getting progressively steeper since 2012, as more and more solar panels are installed across the state, linking to the power network.

By the end of the day, the grid faces a jump in demand: solar energy trickles down to zero just as residents return home and turn on air conditioning units and domestic appliances.

By this year, the California grid needed to bump up its supply by around 13,000 megawatts each evening on a spring day to meet demand, a daily surge three or four times larger than in 2012, the ISO calculates.

As the recent blackouts show, managing these peaks and troughs in energy supply has not been easy.

Negative prices

Excess supply is a problem that’s not specific to power grids. In April this year, a temporary oversupply of crude oil during the economic downturn caused by the Covid-19 crisis drove oil prices temporarily below zero.

negative prices are a long-standing feature of the electricity market

For many, the idea of a seller paying a buyer to take a valuable commodity away seems like an absurdity. But negative prices are in fact a long-standing feature of the electricity market.

According to the IEA, California has negative wholesale electricity prices around 4 percent of the time on average, rising to 8 percent of the time in the spring—or two hours per day, on average.

In Germany, negative electricity prices have become common, and reflect a combination of cheap renewable and inflexible conventional power stations.

Many coal-fired, as well as nuclear power stations, were simply not designed to work at much less than full load, exacerbating the problem of excess supply to grids when solar or wind power is ample.

In Canada’s Ontario province, the IEA calculates, where the problem of overcapacity is particularly acute, wholesale market prices were zero or negative for almost one-third of 2017.

“The idea of having an energy surplus is quite recent,” says the IEA’s Alejandro Hernández.

“But there are systems in which it’s now very likely for you to have surplus energy during certain hours.”

Sharing the load

One way to reduce the likelihood of an energy imbalance causing a blackout is to increase the overall capacity of the electricity grid. But this comes at a cost, according to Chris Bendiksen, head of research at digital asset manager CoinShares.

“You can’t really do anything about production fluctuations as a result of renewables—they are just there,” Bendiksen told New Money Review.

“But what they’ve done in Germany and Denmark—countries with high intermittent renewables penetration—is to increase the capacity of the overall grids quite a lot. This has fed into high electricity costs, which are very unpopular. And it’s made renewables less politically tenable.”

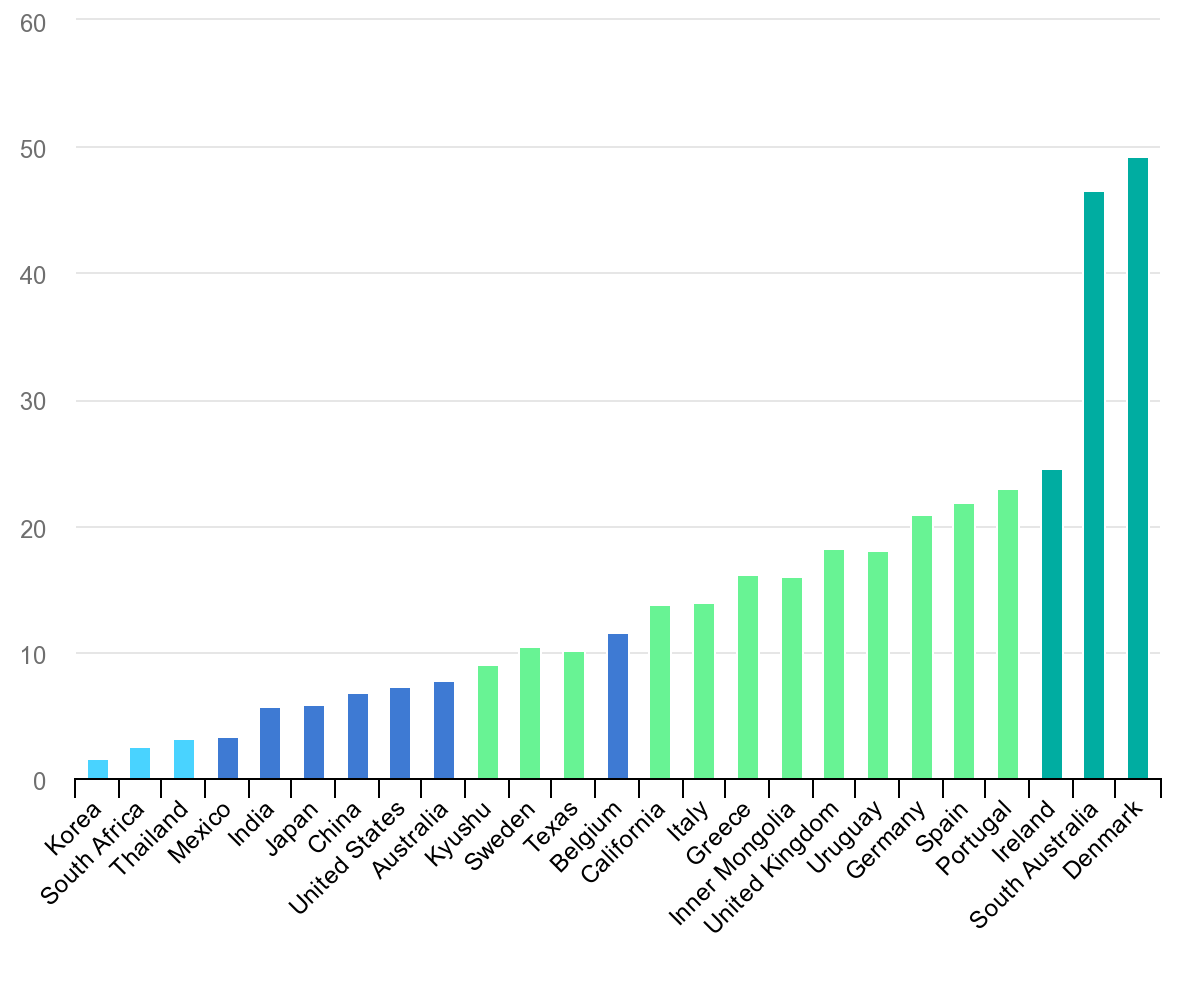

According to the IEA, renewable energy has a 20 percent share of Germany’s electricity grid in 2017, while Denmark had a 49 percent renewables share.

National share of renewable energy in power supply

One obvious solution to local supply/demand imbalances is for countries or regions with a glut of energy to export it to neighbours. But electricity markets are much less open than those for other commodities, like oil, gas and coal.

According to the OECD, only around 3 percent of global gross electricity production was exported across national borders in 2015.

Complicating the picture further, some countries (like Germany) insist on a single internal wholesale price for electricity, causing regional tensions: the wind fields of Germany’s north often have excess supply, but it can’t easily be moved to the industrial, energy-consuming regions of the country’s west and south.

“Mining is going to be a very important puzzle piece in future grids”

According to Bendiksen, cryptocurrency mining is an increasingly obvious solution to these imbalances.

“Cryptocurrency mining should give us the opportunity not to have to beef up electricity grids so much to accommodate renewables,” Bendiksen told New Money Review.

“Mining is the opposite of a peaker plant—a power plant that runs only when there’s high demand. I think this is going to be a very important puzzle piece in future grids.”

Bitcoin’s power consumption

Bitcoin is powered by a network of computers called miners, who compete in a mathematical guessing game to earn monetary rewards (newly minted bitcoins, plus the transaction fees from moving existing bitcoins).

The guessing game involves trillions of virtual ‘spins’—movements of electrons around specially designed microcircuits on silicon chips—and is energy-intensive.

According to researchers at Cambridge University’s Centre for Alternative Finance, the bitcoin network now consumes around 65 terawatt (million million watt) hours of electricity a year, about as much as Colombia or Algeria.

The energy consumption of the cryptocurrency network has been roundly condemned by many outside observers.

“What began as an interesting experiment has morphed into an environmental disaster.” Britain’s New Scientist magazine said in December 2018.

“Now, as the price threatens to dip below $3,000 from a peak of almost $20,000,” New Scientist said at the time, “We should be celebrating bitcoin’s downfall.”

But bitcoin has so far confounded these naysayers. And while its price has remained volatile, it’s since recovered to around $11,400 a coin.

Linking mining and surplus renewables

Meanwhile, some of those involved in producing bitcoin are making increasingly sophisticated connections with the global energy infrastructure.

One US-based start-up called Layer 1, backed by Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel, is already seeking to convert surplus energy into monetary value by mining bitcoin in Texas.

“Public utilities will need to increase their integration with cutting-edge demand response technology”

In May this year, Layer 1 made an explicit link between its ambitions and the problem of surplus renewable energy.

“The increased installation of renewable energy production capacity will require increased demand response services from companies like Layer 1,” said Alexander Liegl, the firm’s chief executive.

“While the increased generation of renewable energy enables the government to meet carbon emission reduction goals, the volatility of green energy production means there’s less certainty of supply for end-consumers. In order to continue guaranteeing energy grid stability, public utilities will need to increase their integration with cutting-edge demand response technology.”

In an interview with Forbes, Liegl said Layer 1 had managed to strike a deal with Texan power generators to obtain electricity supply to mine bitcoin at an all-in cost of 1 US cent per kilowatt hour (kWh).

Like California, Texas has seen regular periods of negative wholesale electricity prices, in Texas’s case predominantly due to an excess supply of wind power.

According to Torsten Dahmen, enterprise solution architect at innogy Innovation, part of German energy supplier E.ON, Layer 1’s reported 1c/kWh bitcoin mining cost in Texas compares very favourably with power obtained from alternative sources.

Dahmen told New Money Review he had modelled bitcoin mining operations that source power from a coal-fired plant and an offshore wind farm and had come up with estimated costs of 3 and 4 cents per kilowatt hour, respectively.

Mining as a service

According to CoinShares’s Bendiksen, Layer 1’s recent Texas deal is an example of how bitcoin miners are now selling themselves to power generators.

“Miners are getting cosy with local utilities”

“These miners are billing themselves as a ‘load as a service’ provider and getting cosy with local utilities,” Bendiksen told New Money Review.

“For example, in an energy grid with a high share of renewables the miner will come in and say, ‘On a normal day of the year, we will come in and take away all your excess load. We’ll make sure you can run everything in your merit order as usual’,” Bendiksen said.

‘Merit order’ is the sequence in which power stations contribute power to the grid, with the cheapest offer—typically made by renewable energy producers—setting the starting point.

“Then the bitcoin miners say: ‘During those times of the year when renewables are not producing enough’—for example where demand is extra-high because of high temperatures and insufficient wind—‘You can give us 15 minutes notice and we will shut down our entire operation’,” Bendiksen explained.

Another deal between a miner and an energy producer shows the idea of linking hydrocarbons and cryptocurrency is spreading.

This week, oil giant Equinor (formerly Statoil), which is majority owned by the Norwegian government, announced it is partnering with a cryptocurrency mining specialist called Crusoe Energy Solutions.

Equinor, which has revenues of over $60bn a year, was recently ranked as the world’s eleventh largest oil and gas producer.

Crusoe, which raised $70m in funding late last year, is backed by Bain Capital Ventures, the KCK Group, Founders Fund, Winklevoss Capital and Polychain Capital.

Under the new deal, Equinor and Crusoe will exploit the natural gas that is a by-product of shale oil exploration in the US/Canadian Bakken oil field, which underlies Montana, North Dakota, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

“By connecting these inverse pains, we can satisfy both needs with no cost”

Equinor says that mining cryptocurrency should be seen as a natural activity for an oil producer, given its need to manage surplus gas. In fact, the firm suggests, it’s almost stupid not to link the two activities.

“Mining cryptocurrency requires a lot of electricity to power computers, while a valuable commodity is wasted, and carbon emissions are created when we flare. By connecting these inverse pains, we can satisfy both needs with no cost to market expense,” the firm’s product manager, Lionel Ribeiro, said in an internal memo reproduced by crypto firm Arcane research.

Gas flaring in North Dakota

According to the Financial Times, the amount of gas burnt off in flares by oil producers jumped to its highest level in a decade in 2019, despite global efforts to eradicate the practice.

Gas flaring caused more than 400m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent gases to be released into the atmosphere that year, according to World Bank data, more than the annual greenhouse gas emissions of the entire UK economy.

The excess supply problem

While the global picture for energy supply and pricing is complex, one broad trend is visible, according to Tim Gould, head of the supply division at the IEA’s World Energy Outlook.

“Periods of negative pricing will increase”

“There’s certainly an expectation that as the shares of wind and solar increase, then periods of negative pricing will increase too,” Gould told New Money Review.

“Post-Covid, there’s also a lot more slack in the system than there might be under ordinary circumstances.”

“On the other hand,” said Gould, “as the pricing of energy becomes more responsive to demand, or if you have more storage in the system, you’re going to even out some of that volatility.”

Cryptocurrencies are far from the only way to store excess supply from the grid. Everyone’s eyes are on the likely future energy take-up from electric vehicles (EVs).

“The growth of EVs—which are currently driving global battery demand—represents a huge potential source of storage and demand-side flexibility,” Peter Fraser, head of the gas, coal and power markets division at the IEA, said recently.

According to Fraser, better energy system design will also help manage intraday peaks and troughs of the type that have recently beset California.

“Smart grids, especially smarter distribution systems, will be better able to manage increasing shares of renewables as well—and they too will likely have more energy storage,” Fraser said.

“For the bubble of people knowing the details, the picture is different”

But it looks likely that, contrary to almost all previous headlines, cryptocurrencies are going to play a central role in the future management of energy resources.

“The broad masses still think bitcoin is used for buying drugs and that it’s a complete disaster for the environment,” said innogy Innovation’s Torsten Dahmen.

“But for the bubble of people knowing the details, the picture is different,” he said.

Sign up here for our monthly newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes