The Wirecard collapse raises questions over the safety of funds kept by electronic money and payment services firms.

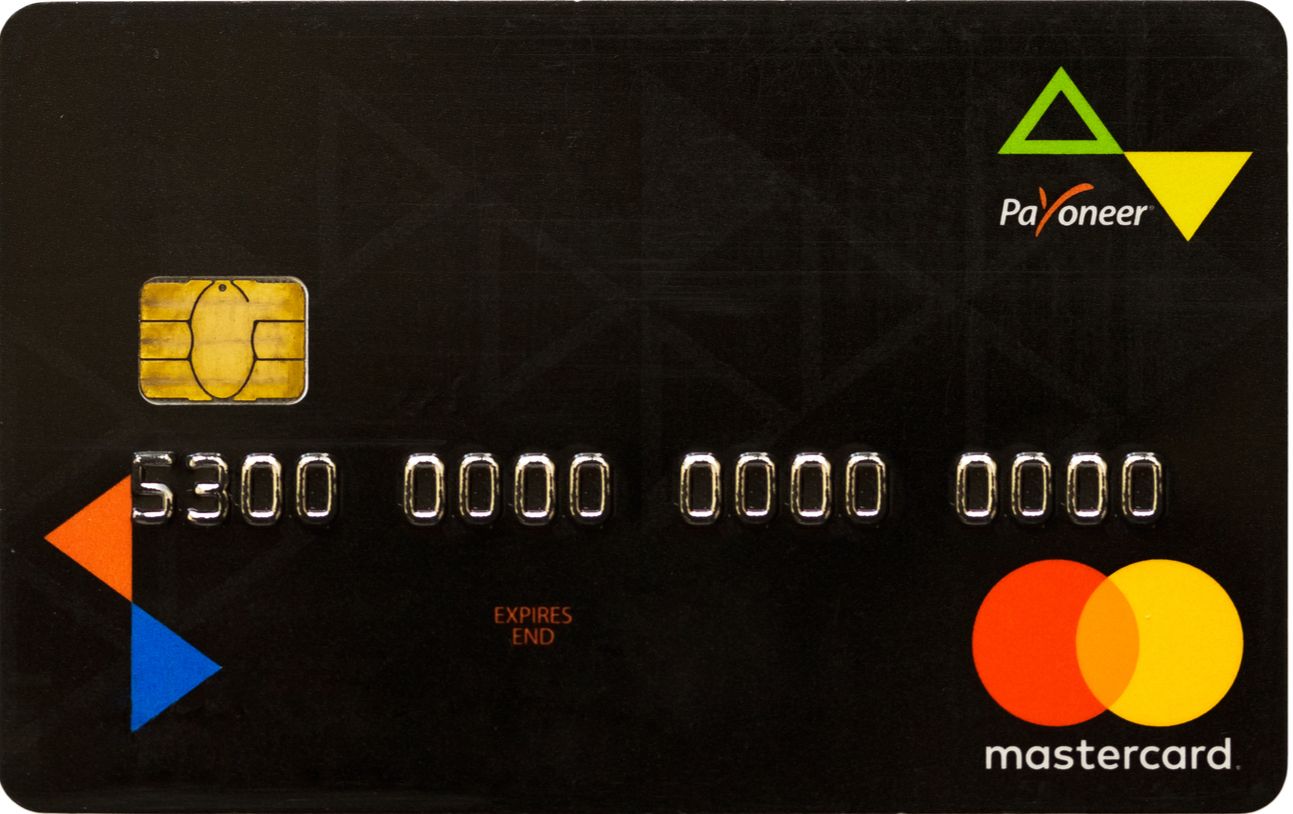

Spot the difference

On the face of it, there’s very little difference between these two debit cards.

They look similar in design. Both run on the Mastercard network, you can add money to both, tap and pay with both, use both in Chip and Pin machines and insert both in ATM machines to withdraw cash.

But only one of the cards has been caught up in the recent Wirecard scandal—the one on the left, run by Payoneer.

That’s because Payoneer’s card was operated by a UK-based subsidiary of the German payments company, which last week filed for insolvency after admitting a €2bn fraud.

That Wirecard subsidiary—Wirecard Card Solutions Limited—had its operations frozen on Friday by the UK financial regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

The freeze, which affected Payoneer and over a dozen similar firms that used Wirecard to process card payments, caused millions of holders of pre-paid cards around the world to lose access to their money.

Meanwhile, clients of UK bank Monzo, the issuer of the card on the right, escaped the funds freeze.

Ironically, Monzo used to give out pre-paid debit cards in exactly the same way as Payoneer—and even used Wirecard Card Solutions as its partner.

But soon after it became a bank in 2017, Monzo stopped offering its clients pre-paid cards. Instead, it started issuing debit cards linked to its clients’ bank accounts. It also gave up its relationship with Wirecard.

“Rest assured, we moved away from using Wirecard when we moved our customers from pre-paid accounts to current accounts back in 2018!” Monzo tweeted last Friday.

Move on, there’s no cause for concern

Late on Monday, the UK regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority, reversed its freeze on Wirecard Card Solutions, allowing Payoneer clients—and those of similarly affected pre-paid card firms—to start to use their money again.

Payoneer says its clients’ funds were safeguarded all the way through the incident and that, apart from the inconvenience of not being able to access their money, they had no cause for concern.

“Rest assured, Payoneer is strong, stable, and working to keep your funds protected”

“Rest assured, Payoneer is strong, stable, and working to keep your funds protected,” the firm tweeted at the weekend.

So is this story over, and was the difference between the Payoneer and Monzo mastercards just a matter of luck?

Did Monzo escape a complex third-party fraud simply by virtue of having changed its card partner at the right time? Can the holders of millions of pre-paid debit cards around the world now breathe a sigh of relief?

The firms caught up in the freeze want to move on from the incident.

“Wirecard Card Solutions Limited is pleased to report that, following intensive work undertaken in conjunction with the Financial Conduct Authority, it has now received consent to resume its operations as the FCA is satisfied that client money is safe,” the firm now says on its website.

What is e-money?

There’s one key legal difference between Monzo and Payoneer.

While Monzo is a bank, Payoneer operates under a European electronic money (e-money) licence, as does Wirecard’s payments processing subsidiary.

“Wirecard Card Solutions Ltd is authorised by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) under the Electronic Money Regulations 2011 for the issuing of Electronic Money,” the firm’s website says.

“E-money is a claim on an issuer stored in electronic form”

Europe’s e-money regime is nearly two decades old and was created—with foresight, most observers would say—to regulate and support the fast-growing internet commerce and electronic payments sector.

E-money licences are easier to obtain, come with less intrusive supervision and have much lighter capital requirements than a banking licence. In the past, as Monzo has shown, they can also be used as a stepping stone to full bank status.

Many other fast-growing European financial technology (‘fintech’) firms, such as Revolut, are still e-money institutions.

“E-money is basically a claim on an issuer stored in electronic form,” explains Simon Gleeson, a partner at law firm Clifford Chance, in his recent book, ‘the Legal Concept of Money’.

But it’s not just any kind of electronically stored value. E-money must be capable of being used to make payments to someone other than the issuer, Gleeson says.

On that definition, for example, an Amazon e-voucher or a store discount card are not e-money. Nor are credit cards: for something to be e-money, it must be issued on the receipt of funds, rather than on the basis of a loan.

“All electronic money institutions (EMIs) are required to safeguard funds”

But what does the difference between a bank and an electronic money institution mean when it comes to the safety of your funds?

If you hold money on a bank-issued debit card, you are a depositor in the bank and you have effectively lent the bank your money. If the bank goes bust, your funds are at risk, which is the reason why most countries operate retail deposit insurance schemes.

“Any money in your Monzo account is fully protected up to £85,000 by the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS). That means that if Monzo ever went out of business, you’d get your money back up to £85,000,” Monzo says on its website.

But there’s no compensation scheme for e-money holders, and for a reason. Unlike banks, e-money firms don’t lend out depositors’ money: they have to maintain a 1:1 ratio between the customer funds they take in and the e-money they give out.

Nevertheless, the e-money regime still requires client deposits—such as the funds loaded onto pre-paid debit cards—to be set aside formally from the card issuer’s own funds.

“All electronic money institutions (EMIs) are required to safeguard funds received in exchange for e-money that has been issued,” the FCA says.

E-money firm Revolut explains the promise on its website.

“Though we are not the same as a traditional bank, your money is protected,” Revolut says.

“Funds with Revolut remain safeguarded in accounts with a tier one UK bank, as per our obligations under the e-money regulations. Plus, all of your card transactions are processed by the Mastercard or Visa network and are protected by Mastercard or Visa rules.”

Safety of client e-money under question

When freezing the activities of Wirecard Card Solutions last Friday, the FCA said it felt it needed to step in to ‘protect the electronic money funds of consumers’.

Why was the regulator apparently concerned that the safeguarding framework might not be as robust as intended? Why did some of the affected card issuers, such as Payoneer and Anna Money, feel the need to declare that they would cover any shortfall? Hadn’t the funds been properly segregated?

“The whole scheme of safeguarding is predicated on a kind of fiction”

According to industry experts, the e-money safeguarding regime is more complex—and legally less certain—than advertised.

The underlying principle is clear, says Nicholas Thompsell, a partner at law firm Fieldfisher.

“If an e-money issuer receives funds in return for the issuance of e-money, from the moment of the issuance of the e-money it should safeguard those funds until the e-money has been redeemed,” Thompsell told New Money Review.

But in practice, said Thompsell, it may be difficult to work out what funds belong to whom at any moment in time.

“The whole scheme of safeguarding is predicated on a kind of fiction: that there’s this bag of money being passed like a football from one person to another,” Thompsell said.

“That’s not how modern payments work. There isn’t such a thing as ‘the money’. There are balances that one firm has with another firm, which reflect balances with a third firm, and so on.”

“If you have a payments chain, it can be quite complicated to work out what money you’ve received and what money you’ve paid out,” Thompsell said.

According to Alison Donnelly, a director of compliance consultancy fscom and a former FCA policy advisor, the challenge of attributing e-money to its owners is exacerbated by the sheer volume and variety of transactions involved.

“In theory, safeguarding is straightforward. But when there are multiple transactions, throughout the day and night and over the weekend, using different routes and in different currencies, it just becomes hugely complex,” Donnelly told New Money Review.

The result is that, if an e-money or payments services firm were to enter administration, as Wirecard’s UK subsidiary was reportedly on the verge of doing on Monday, customer funds may not be easily identifiable.

“The problem with safeguarding is that whilst the legislation is pretty much black and white, there are lots of gaps,” Donnelly said.

“You have to rely on the firm doing the right thing on the day it goes bust”

“You have to rely on the firm doing the right thing on the day it goes bust. You could be safeguarding perfectly every day until then, but things could go wrong. All the creditors could then line up and say, ‘this isn’t client money, it’s mixed with company funds and I have a claim’.”

One recent case backs up Donnelly’s observation.

Customers of Supercapital, a UK payment services firm that entered administration in October, are still waiting to retrieve their money and have already been told by the administrators that they are likely to lose at least 10 percent of their funds, despite being covered by the safeguarding regime.

In one famous client money case, some creditors of Lehman Brothers—the admittedly complex financial company insolvency that triggered the 2008 financial crisis—have had to wait over a decade to have their claims addressed.

But the evidence suggests that customers of a bankrupt e-money or payment services firm may also have to rely on the courts to get their money back—a process that’s unlikely to be quick—as well as facing the loss of some of their money.

“The UK safeguarding legislation derives from European directives, but it’s the FCA’s interpretation of those rules for use within the UK and with UK insolvency law in mind,” Donnelly said.

“The FCA has no control over the insolvency rules and, if it comes to a dispute, it will probably be down to a judge to interpret them.”

For some of those using e-money debit cards to store savings, shop online and pay bills, the Wirecard crisis has come as an unpleasant wake-up call.

“Never touching that card again, first thing after hopefully getting our money back is to cut the card in half,” one member of a Payoneer support group said this week on Facebook.

On July 2, many group members said they were still not able to withdraw cash using their cards, or were able to do so only in limited amounts. Some reported being charged much higher fees than normal by ATM providers.

Whether this event has repercussions for the broader fintech sector and the electronic payments system, which now plays such a vital role in the world economy, remains to be seen.

Sign up here for our monthly newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes