When you place money on deposit you expect to get it back.

Many people say that’s the original concept of banking: you pass your funds across a desk into safe hands, they give you a receipt, and those funds are not supposed to be given out to someone else, even if the other person promises to return them and to pay you for the use of your money in the meantime.

In fact, that’s not how banking has worked for a long time, and banks do lend out their deposits—many multiples of them.

Wirecard is primarily a story about unbacked stablecoins

But the idea of a so-called ‘fully reserved’ bank has never gone away. It’s enjoyed renewed popularity since the 2008 financial crisis. And it underlies many current concepts in money: stablecoins, for example.

When you buy a stablecoin you want it to be backed 100 percent by something else of value. If the issuer of the stablecoin disappears, no problem. You turn up to the (virtual) vault where your funds are stored and get them back.

This week’s dramatic insolvency of German payment firm Wirecard is primarily a story about $1.9bn in missing funds—unbacked stablecoins, as it were.

Wirecard told others it had those funds in reserve. It even got its auditor, EY, to vouch for that promise, but the money turned out not to be there.

In itself, this is probably the biggest accounting scandal since the former top 5 auditor Arthur Andersen was felled by Enron in 2001.

Wirecard’s collapse also threatens to have knock-on effects on other fintech businesses, with client funds at several other pre-paid card businesses, both in the UK and the US, temporarily frozen. The affected card providers had all used a Wirecard subsidiary to handle their own payments.

But in the details of the corporate failure there’s also an uncanny echo of another recent stablecoin saga—tether.

Both stories involve money supposedly lost at third-party payment processors, specialist intermediaries that have grown hand-in-hand with the dizzying rise of internet commerce.

Financial Times reporter Dan McCrum provided evidence last year that much of the business reported by Wirecard’s network of third-party processors had simply been invented.

Wirecard sued the FT over its report, accusing the publication of working hand-in-hand with short sellers and causing the FT to incur heavy legal bills.

“What Wirecard appears to have convinced its auditors [EY] was going on,” McCrum said earlier today, “was that it was sending lots of payments processing to these businesses [third-party payment processors in Dubai, the Philippines and Singapore], and then those processors were doing it for Wirecard, and paying [Wirecard] a nice big commission.”

By contrast with Wirecard, tether didn’t have public investors to impress, just a decentralised network of cryptocurrency users.

But tether’s owner (crypto exchange Bitfinex) lost money in 2018 in exactly the same way as Wirecard has apparently done now: $900m of cash passed through payment processors simply disappeared.

The lost reserves caused the stablecoin’s asset backing to fall from a 100 percent ratio to just 74 percent.

Tether operates on five different cryptocurrency blockchains and is run by British Virgin Islands shell companies

But unlike Wirecard, tether hasn’t disappeared, despite the allegations of missing funds. Strangely enough, the opposite has occurred: instead of losing investor confidence, the cryptocurrency has grown fourfold in market size since the rumours of lost money first surfaced.

Noone knows for sure how much cash is missing—tether has never undergone a full audit. Its supporters say tether’s recent asset growth is testament to the digital currency’s utility as a black market dollar.

By comparison with the existing financial system, transactions in tether settle quickly, allowing counterparties around the world to exchange tether tokens at close to their target $1 value.

“Tether is disrupting the legacy financial system by offering a more modern approach to money,” Bitfinex says.

Unsurprisingly, law enforcement bodies have found it easier to target a centralised entity like Wirecard—the German firm is now bust and its ex-CEO has been put under house arrest—than tether, which operates on five different cryptocurrency blockchains and is run through British Virgin Islands shell companies.

Tether has so far faced down the civil lawsuits it faces from the New York State Prosecutor and disgruntled US investors.

New, trusted stablecoins are likely to appear

As money goes wholly digital and businesses, governments, cypherpunks and algorithms all get into minting their own asset-backed currencies, the safety of investors’ cash looks set to remain a hot topic.

Frauds will likely recur, funds will go astray again and working out which structure is safe is not going to be easy. But new, trusted stablecoins are likely to appear, and they may well prosper.

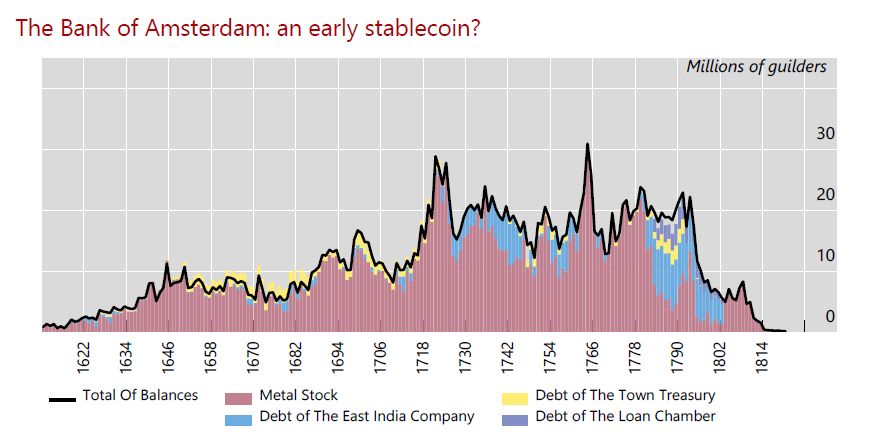

“Full reserve banking is up for grabs”, says financial historian Simon Lelieveldt, citing the example of the Bank of Amsterdam, which managed to run for over 100 years after its creation in 1609 as a pure deposit institution, not lending out its clients’ gold and silver on any significant scale.

Perils lie ahead for would-be stablecoin issuers

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the main policymaker for the legacy financial infrastructure, is already thinking in terms of the parallels between old banking models and new digital stablecoins.

A forthcoming BIS paper, co-authored by researchers Jon Frost, Hyun Song Shin and Peter Wierts, will look at the lessons from the rise and fall of the Bank of Amsterdam.

From a forthcoming BIS working paper, “From stablecoin to proto-central bank: lessons from the rise and fall of the Bank of Amsterdam”

Perils lie ahead for would-be stablecoin issuers. As more and more issuers launch digital currencies and with the rising threat of negative interest rates, it will be harder than ever to resist the temptation to recycle depositors’ money into loans to earn some extra return.

For those who do, the BIS’s stablecoin chart offers a history lesson: a hundred years from its founding, the Bank of Amsterdam did a tether, as it were: it departed from its promise of backing its proto-stablecoin with safe and liquid reserves.

Instead, it started to make loans to the Dutch East India Company, perhaps the most powerful corporation in the world at the time. Some of these loans went wrong and within a few decades the Bank of Amsterdam was bust.

These days, as the Wirecard implosion has shown us, events unfold a lot faster.

Sign up here for our monthly newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes