Today’s dramatic collapse in the oil price is the latest confirmation of an economic slump that central banks and governments appear powerless to halt.

Benchmark oil prices, measured by the May West Texas Intermediate (WTI) futures contract, traded as low as -$40. This meant those buying oil today were paid by sellers to take it off their hands.

May WTI future

The negative oil price reflects a huge supply glut as a result of reduced global economic activity in the wake of the corona pandemic.

Storage tanks in Cushing, Oklahoma, where trades in the West Texas Intermediate futures contract settle, have no more space, with some observers predicting all US oil storage capacity will be full within two weeks.

Today’s oil crash adds to signs of increasing strains across the world’s physical, energy and financial infrastructures.

Last week the UK’s electricity supply network, the National Grid, said that record low demand for electricity during Britain’s coronavirus lockdown could lead to windfarms and other renewable power plants being turned off.

As nuclear power plants can’t easily be disconnected from the grid, power gluts can force the producers of wind, solar, geothermal or hydroelectric energy to quit the market.

The UK’s energy infrastructure has been showing signs of strain in a series of episodes apparently linked to fluctuating or falling demand.

In 2019, according to the Guardian, the National Grid suffered three blackout ‘near-misses’ in as many months before a major outage in August left almost a million homes in the dark and forced trains to a standstill around the UK.

Oil markets are not the only energy sector to have seen negative prices in recent months.

For example, gas producers in Texas have been also left with hydrocarbon assets they cannot pay consumers to accept.

Some of these producers are flaring their excess gas into the sky illegally, producing fires so large they can be seen from space.

Meanwhile, other gas producers are building plants to convert excess hydrocarbons into bitcoin. This bitcoin can then be traded for cash, offering the producer some chance of salvaging a return.

It’s not just commodities that can’t be given away. Money, in the form of government debt, also carries negative interest rates across $12 trillion of the world’s bond markets.

This means a bond buyer has to pay the bond issuer, the borrower, for the privilege of owning its bonds.

In the depression of the 1930s, the last major worldwide episode of deflation—falling prices economy-wide—the US central bank allowed the money supply to contract by about a third between 1929 and 1932, with money in issue dropping in tandem with economic activity.

Later, this was seen as a major policy error.

In 2002, Ben Bernanke, later the governor of the US central bank, the Federal Reserve, said that the US had learned its lessons and that under a fiat money system it should always be possible to reverse a deflation by printing money.

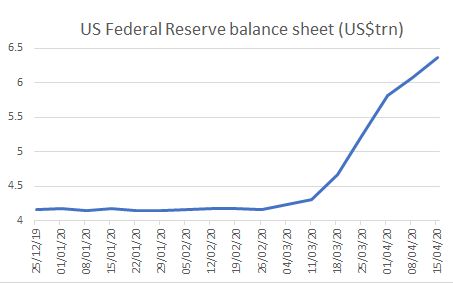

The US central bank has been practising what Bernanke preached: in response to the coronavirus pandemic, the Federal Reserve has already increased its balance sheet, the basis of the US dollar money supply, by over 50 percent in a little more than a month.

US Federal Reserve balance sheet

“If we do fall into deflation, we can take comfort that the logic of the printing press example must assert itself, and sufficient injections of money will ultimately always reverse a deflation,” Bernanke said in his 2002 speech.

However, today’s oil price collapse adds to evidence that the deflationary forces unleashed by the coronavirus pandemic are now overwhelming governments’ and central banks’ money-printing efforts. Bernanke may have got it wrong.

Keep up with New Money Review content: sign up here for our newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes