It’s a hat trick. With uncanny timing, Robert Shiller has done it again.

The Nobel prize-winning Yale University professor warned of irrational exuberance at the peak of the 2000 dot.com boom and of a US housing crash in 2007, a year before the 2008 financial crisis. Last year, he turned his analytical gaze to viruses just a few months before the outbreak of the corona pandemic.

In his latest book, ‘Narrative Economics’, Shiller compares viral epidemics and economic narratives and concludes that they are pretty much the same. You can model a narrative like a virus, he says, using exactly the same mathematics.

Rather than abstract econometric models, it’s more often shared stories that help drive economic events, says Shiller.

And, as we are currently witnessing, financial panics can spread like epidemic viruses—and the two can feed off each other.

Shiller backs up his arguments with data. If the epidemiologist uses his testing kit to assess the spread of a virus through the population, Shiller’s raw material is frequency distributions—specifically, the frequency with which set words or phrases have appeared in the past in books, magazines and newspapers.

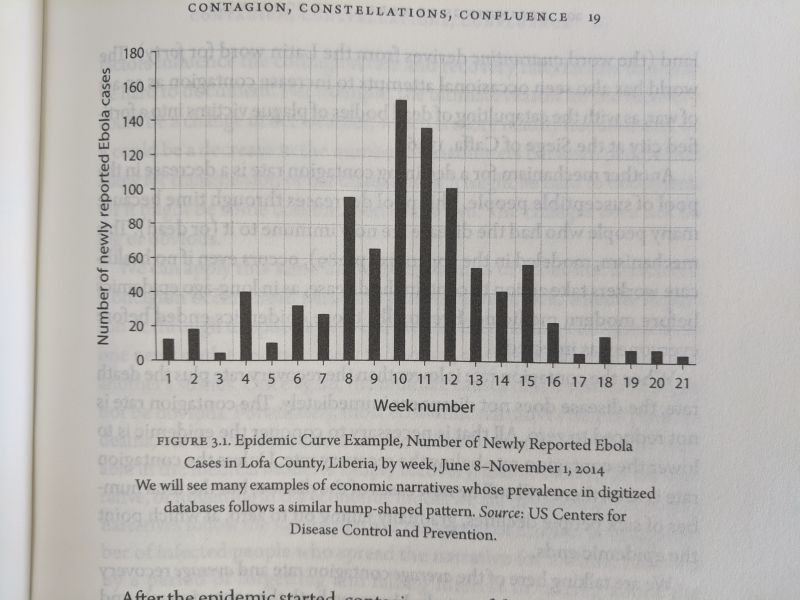

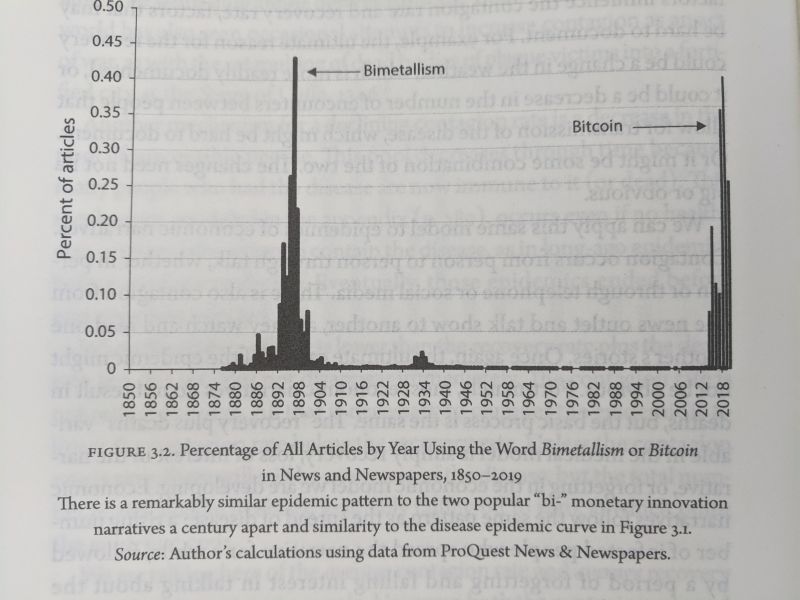

Using bar charts, he shows how the epidemic curves of past viral outbreaks like Ebola have a similar hump-shaped pattern to those of economic viruses.

Shiller uses the narrative of bimetallism in the late 19th century USA and the ongoing narrative of bitcoin to prove the point (in fact, he explicitly links bimetallism and bitcoin as examples of popular dissatisfaction with the economic status quo, even though they occurred 120 years apart).

Epidemic one—Ebola

Epidemic two—bimetallism and bitcoin

Shiller chides professional economists for refusing to take public narratives—the virality of stories—into account.

“Economists’ one-year forecasts have been on the whole worthless”

As a result, he argues, economists are unable to drive except by looking in the rear-view mirror. This leads to predictable results.

“No economist gave a credible forecast of the worldwide nature of the Great Depression of the 1930s before it happened,” he writes.

“Traditionally, economists who study data have excelled in creating abstract theoretical models and in analysing short-run economic data. They can accurately forecast macroeconomic changes a couple quarters into the future, but for the past half-century, their one-year forecasts have been on the whole worthless.”

It’s easy to be an expert after the event, but a lot tougher to predict things before they happen.

When it comes to our present public health crisis and the economic disruption it is causing, there is both good and bad news.

The good news is that things will get better. Viruses always peak and then decline in their impact.

“Not everyone will catch the disease,” Shiller says in a chapter explaining epidemic models.

“Some people escape the disease completely because they do not have an effective encounter with an infective. The environment gradually becomes safer and safer for them because the number of infectives decreases as they get over the disease and become immune to it. Eventually, the infectives almost disappear and the population consists almost entirely of susceptible and recovered.”

The bad news is that our systems—both medical and economic—may not be robust enough to cope with the outbreak.

For the time being, political leaders are largely following the advice of public health bodies in seeking to control the advance of coronavirus.

With stories, things can go very wrong, very quickly

But what about the broader repercussions of viruses? Here things are much trickier to manage.

First, the economic impact of narratives may change through time. One virus can build on and then feed off another, in what Shiller calls a constellation of narratives.

More worryingly, while a vaccine may head off a viral epidemic, there’s not necessarily any antidote to a destabilising economic or political story.

Citing research by Soroush Vosoughi, published in Science in 2018, Shiller points out that false stories have at least six times the retweeting rate on social media platform Twitter than true stories.

Bad news can go viral easily, especially when embellished with lies and hate. Good news doesn’t make the front page.

With stories, things can go very wrong, very quickly. According to Shiller, citing sociologist Stephen Van Evera, there’s a convincing argument that World War I started because of a false narrative.

According to Van Evera, a narrative that he called ‘the Cult of the Offensive’ incentivised the European powers of the time to attack each other. The idea was that first movers in war win.

In our current hyperlinked world, it’s easy to see that the ability to disseminate false narratives is dangerous.

What can we do? Maybe we all need to spend less time on social media and outside breathing fresh air—at a safe distance, of course.

But the implications of Shiller’s work are much broader. Our economic, financial, physical and social infrastructure needs to be much more robust, better able to cope with surges in demand. The networks we use for our everyday lives must be more distributed and less centralised.

Any economic and financial models based on Gaussian probability modelling—those using the language of standard deviation and normality—need to be discarded, as they are not just wrong, but dangerous.

Because information can cascade and create epidemics, speculative bubbles can ultimately be seen as perfectly rational, the opposite of what economics textbooks tell us.

Finally, Shiller says, economic behaviour can never be properly understood without taking infectiousness into account.

In a year in which Covid-19 has paralysed the world economy, it may be a relief to remember that viruses are everywhere.

Don’t miss any more New Money Review content: sign up here for our newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes