If you thought investing in cryptocurrencies was risky, try making them.

An estimated 4.3 million bitcoin mining machines around the world now perform around 82 exahashes (million trillion hashes) per second in their race to create new units of the cryptocurrency.

Miners spin a virtual roulette wheel to mint new coins, expending electrical energy to do so.

Bitcoin’s annual energy consumption is now estimated at 73 terawatt (million million watt) hours, equivalent to the energy requirements of the whole of Austria, or 0.3% of the world’s total electricity use.

According to the cryptocurrency’s critics, this makes bitcoin an environmental disaster. According to bitcoin’s supporters, its heavy energy consumption means it is the most secure computing network in the world.

This is because bitcoin is decentralised, and any attacker seeking to subvert the bitcoin system would need to take over at least half the nodes in the network, incurring a dramatic energy cost.

Meanwhile, miners continue to join the virtual gold rush: at its recent peak of over 100 exahashes per second, recorded on September 26, bitcoin’s aggregate processing speed had increased more than threefold from a low reached in December 2018.

Bitcoin’s hash rate

As a currency, bitcoin is notoriously volatile: its price reached a peak of just under $20,000 in December 2017 before slumping to the low $3,000s a year later.

This year, the cryptocurrency rose as high as $13,800 a coin in July before falling back to its current level of around $8,200.

But if those price swings seem dramatic, those in the bitcoin mining hardware market are even more so.

The Antminer S9, a bitcoin mining unit manufactured by Bitmain, saw its secondary market price collapse by 98% during the 2018 bear market.

“In the fourth quarter of 2017 the price of an Antminer S9 hit $4500,” Matt d’Souza, CEO of Blockware Solutions, a broker of crypto mining hardware, told New Money Review.

“But by December 2018 it was selling for as little as $75,” he said.

Now, says d’Souza, those wishing to enter the bitcoin mining business also have to contend with the arrival of new, more powerful machines.

Bitmain’s Antminer S17, for example, which is currently listed as out of stock on the company’s website, performs 64 terahashes per second, compared to the S9’s 14 terahashes.

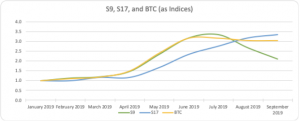

This performance gap is now being reflected in the secondary market for mining equipment, says Blockware.

“Everyone’s switching to the S17,” said d’Souza. “We stopped buying S9s in the secondary market around May this year. The S17 can handle the increasing difficulty associated with the rising bitcoin hash rate.”

As a result, says d’Souza, while the secondary market price of an Antminer S9 dropped from around $550 in June to $300 in September, the S17 has held its value better during a period of price declines for bitcoin.

Source: Blockware solutions

But coping with the volatile price of hardware is only one of the challenges facing prospective bitcoin miners.

Others include negotiating long-term electricity deals with energy suppliers, securing dependable hosting rates with internet providers and, in some countries, avoiding predatory interest from government authorities or the mafia.

Venezuela’s central bank, for example, was recently accused of trying to launder bitcoins gained from seized mining equipment.

A January 2018 report in Hackernoon described bitcoin miners in Venezuela operating in fear of the local police and organised criminals.

And as cryptocurrency miners operate in one of the few markets with perfect global competition, they have to contend with those in other countries able to operate with extra-cheap electricity, obtained by fair means or foul.

Earlier this year, there were reports of mining consortia from around the world seeking to operate in Iran due to the country’s rock-bottom electricity prices.

Iran was reportedly charging as little as $0.006 per kilowatt hour for electricity, ten times cheaper than the $0.06 rate often assumed by cryptocurrency analysts as an input cost.

Iran has since said it will introduce a legal framework to recognise the mining of cryptocurrencies, but has yet to do so.

In August, the Ukrainian security service announced it had stopped a ring of computer hackers who had broken into one of the country’s nuclear power plants to power their mining rig.

Using nuclear fission to generate bitcoin appears to be a theme in the former USSR: earlier this year, the president of neighbouring Belarus said he wanted to site a crypto mining facility near a new nuclear power plant of his own.

And more prosaic risks remain for those plugging bitcoin mining hardware, which generates lots of heat, into the electricity network.

According to a tweet on 30 September from analyst Marshall Long, a data centre in China operated by Innosilicon recently caught fire, destroying $10m-worth of cryptocurrency mining equipment.

Don’t miss any more New Money Review content: sign up here for our newsletter

Support New Money Review on Patreon or in cryptocurrency