A new initiative by global governments to combat money laundering risks driving financial activity out of the reach of law enforcement agencies, say tech experts.

FATF addresses ‘growing misuse’ of cryptocurrencies

Last week the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) tightened its rules on virtual assets, a category that includes cryptocurrencies like bitcoin.

FATF was established in 1989 by the G7 countries to address a perceived increase in global money laundering. Its list of members has expanded from the founders (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US) to include 36 national governments.

The US currently acts as president of FATF, where its one-year term expires on June 30 2019.

FATF regularly publishes statements that identify high-risk countries based on assessments of their anti-money-laundering and counter-terrorist-financing policies. Currently, FATF blacklists two countries, Iran and North Korea.

“I commend efforts to address the growing misuse of cryptocurrencies”

In a statement issued by the US Treasury to mark the issuance of the new FATF initiative, Steven Mnuchin, secretary of the Treasury, cited the use of cryptocurrencies like bitcoin as a particular concern.

“One of the most valuable contributions of this plenary is the regulation of all virtual assets, especially cryptocurrencies,” said Mnuchin.

“I commend efforts by the FATF to address the growing misuse of cryptocurrencies and other virtual assets by money launderers, terrorist financiers, and other illicit actors.”

In November last year Mnuchin warned SWIFT, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications, to disconnect several Iranian banks to avoid sanctions exposure.

SWIFT is an encrypted messaging network that helps financial institutions transmit information to each other securely. It acts as the backbone of the international money transfer system. The banks participating in the SWIFT network moved quickly to toe the US line.

A focus on intermediaries

FATF’s new rules focus on a type of intermediary called a Virtual Asset Service Provider (or ‘VASP’).

Virtual assets, says FATF, are a digital representation of value that can be digitally traded or transferred, and can be used for payment or investment purposes.

Virtual Asset Service Providers include cryptocurrency exchanges, whether they are involved in converting cryptocurrency to or from fiat currencies, or only to other cryptocurrencies.

The VASP category also includes entities that help transfer virtual assets, those safekeeping or administering virtual assets, and those providing financial services for issuers of virtual assets.

Henceforth, says FATF, any VASP “must obtain, hold, and transmit required originator and beneficiary information, immediately and securely, when conducting virtual asset transfers.”

The new rules will force cryptocurrency exchanges to pass information about their users to each other

The originator of a virtual asset transfer, says FATF, is the account holder who orders the transfer or, where there is no account, the person that places the order with the intermediary to perform the transfer. The beneficiary is the account or person receiving the transfer.

Some cryptocurrency networks, like bitcoin, have no concept of accounts or account holders. Instead, bitcoins ‘exist’ in the network history, called a blockchain, merely as the unspent outputs of previous transactions.

Each bitcoin is therefore linked by a series of transactions to its origin as a newly minted (or ‘mined’) coin.

The net effect of FATF’s new rules will be to force cryptocurrency exchanges to pass information about their users to each other when conducting transfers.

FATF says that this user information should also be shared with law enforcement bodies, on request.

While the FATF rules are not binding, the US Treasury Secretary made it clear that he expects other countries to comply with them.

“The United States calls on all nations to join us in ensuring the FATF’s standards are implemented globally, and standing together against those who threaten the security of the international financial system,” said Mnuchin.

In the past, the US government has been able to compel financial institutions from other countries to follow its sanctions regime, levying heavy fines on those seen as unwilling to toe the line.

The FATF approach doesn’t work

In issuing its new guidance, FATF ignored warnings from across the cryptoasset industry that the new rules won’t work.

Chainalysis, for example, a data analysis company with strong ties to law enforcement agencies, said earlier this year that it simply isn’t possible to identify the two people at the ends of a transfer in virtual assets.

Chainalysis says it helps governments to detect criminal activity and suspicious financial connections in cryptocurrencies.

“Requiring a transmission of information identifying the parties is not feasible”

“Virtual assets are designed to move value without the need to identify the participants in a transaction,” the firm’s co-founder, Jonathan Levin, said in an April public letter to FATF.

“In fact, in most circumstances, VASPs are unable to tell if a beneficiary is using a VASP or their own personal wallet in any given transaction. Therefore, requiring a transmission of information identifying the parties is not feasible,” Chainalysis said.

Global Digital Finance (GDF), an industry body that aims to introduce best practices in cryptoassets and digital finance technologies, also questioned FATF’s approach.

The requirement to obtain and hold information about originators and beneficiaries “appears to presuppose that an originating VASP has access to other information on the beneficiary apart from the wallet address, which it does not,” GDF said.

It also warned that cryptoasset users can easily sidestep the FATF constraints on intermediaries.

“This requirement can easily be circumvented by interposing peer-to-peer (“P2P”) transfers or non-custodial wallets, which cannot be stopped,” GDF said.

A custodial wallet for virtual assets like bitcoin is operated by a trusted third party, like an exchange, which would have knowledge of the wallet owner’s identity, as well as control over the private keys that allow the virtual asset to be transferred.

However, non-custodial wallets allow users to control their own private keys.

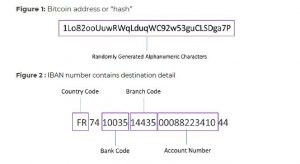

In its comment letter, the GDF provided an illustration showing the central difference between a bank account and a bitcoin address.

It showed an IBAN number, the bank account identifier that provides the country, bank code, branch code and account number of the account holder.

By contrast, said GDF, a bitcoin address is simply a randomly generated selection of letters and numbers, with no information tying the address to a particular identity or institution.

A bitcoin owner can generate as many addresses as he/she wants from the same pair of cryptographic keys, without cost.

Those focused on privacy recommend using a single bitcoin address only once: again, this is a departure from the idea of a bank account that’s tied to a single identity.

Bitcoin address vs. IBAN number

Driving financial activity to the edge

The net effect of the new FATF rules is likely to be counterproductive for those trying to tighten the sanctions regime, say some observers.

“The requirement to share sender and recipient information could not only compromise customers’ data privacy, but would potentially impede the FATF’s objectives by pushing trading volume underground,” Obi Nwosu, chief executive of cryptocurrency exchange Coinfloor, told New Money Review.

“This contentious recommendation also needs to be detailed more,” said Nwosu.

“For example, if it only pertains to transfers directly to other VASPs, then exchanges and custodians may simply require all transfers out to go to a client’s personal wallet addresses. In this case it could spur the growth in usage of crypto wallets, which is a good thing,” said Nwosu.

Asked whether FATF’s approach could severely hinder cryptocurrency exchanges in their work with clients, Nwosu was equivocal.

“I’m not sure it’s bad for exchanges,” he said.

“It might mean slightly increased hassle for customers, with a few extra steps needed for them to transfer between exchanges,” he said.

“But, who knows, some inventive wallet developers may come up with additional features to help reduce or eliminate the increased operational overhead incurred by the end consumer,” he said.

“Even Chainalysis thinks it’s stupid”

Adam Ficsor, the creator of Wasabi, a non-custodial bitcoin wallet, was scathing about FATF’s approach.

“Even Chainalysis thinks it’s stupid,” Ficsor told New Money Review.

Ficsor warned that the FATF rules do little to protect users of cryptocurrency against their primary risk—having their private keys stolen. At least $15bn in cryptocurrencies have been stolen from custodial wallets at exchanges or other central storage venues since 2013, according to one estimate.

“Custodial businesses should be regulated to be accountable to their customers, not their customers to be accountable to them. The custodial businesses can steal the money of their customers, not the other way around,” said Ficsor.

While FATF’s approach could benefit businesses like his, said Ficsor, it did not benefit cryptocurrency users overall.

“Making custodial services’ job unreasonably hard in the wrong way is good for non-custodial businesses, like ours, but I won’t cheer just because it benefits me,” he told New Money Review.

Don’t miss any more New Money Review content: sign up here for our newsletter

Support New Money Review on Patreon or in cryptocurrency