The world’s central banks are proving reticent to introduce digital currencies, despite mounting market pressures for them to do so, according to a new report from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

In a new survey, the BIS polled central banks in 63 countries about their attitudes to the issuance of digital currencies. The countries represented by the survey respondents cover around 80 percent of the world’s population and over 90 percent of global economic output, says the BIS.

Pressure to introduce central bank-issued digital currencies (CBDC) is rising as a result of technological change and evolving consumer habits.

Payment technology is changing at an accelerating pace, says the BIS, noting that consumers expect faster, easier payments anywhere and at any time, mirroring the digitalisation and convenience of other aspects of life.

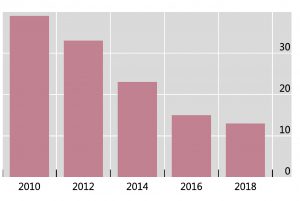

In Sweden, for example, a country where digital payment is now dominant, the value of cash in circulation has fallen from around 3 percent of GDP in 2010 to just over 1 percent now.

And only around 10 percent of Swedes paid for their most recent purchase in cash, compared to around 40 percent in 2010.

What percentage of Swedes paid for their most recent purchase in cash?

“The country’s retailers have good reason to expect that the decline will continue and the cost of accepting cash will become prohibitive, so that it will no longer be accepted in the future,” says the BIS, citing recent research from Sweden’s central bank.

However, the accelerating disappearance of cash payments presents central banks with a real policy dilemma.

Traditionally, central banks have issued money in two forms: cash (notes and coins) for retail users; and reserve or settlement accounts for wholesale users.

These reserve accounts are typically accessible only to large financial market players, such as banks, broker/dealers and financial market infrastructures like securities depositaries.

Now, notes the BIS, central banks could issue three distinct versions of digital currency, each blurring the historical divide between central bank money and the money created by banks and held within the commercial banking system.

First, says the BIS, a central bank could issue a general-purpose account-based digital currency, effectively granting the public direct access to accounts at the central bank. Up to now, central banks have shied away from this option as it could deplete the deposits held at banks, with knock-on effects on bank lending and the stability of the banking system as a whole.

The second option is for a central bank to issue general purpose, but token-based (rather than account-based) digital cash. Two pilot projects involving the issuance of such token-based cash have already taken place in Sweden and Uruguay.

Finally, notes the BIS, central banks could issue restricted access digital tokens for the wholesale settlement of interbank payments or securities transactions.

However, the BIS says, central banks have failed to move much beyond the planning stage when it comes to digital currencies.

Although 70 percent of the respondents to the BIS survey said they were working on CBDC through research or proofs-of-concept, only five of the 63 central banks surveyed had progressed to pilot projects and no central bank has yet declared firm plans to issue a CBDC.

“Most central banks appear to have clarified the challenges of launching a CBDC but they are not yet convinced that the benefits will outweigh the costs,” says the BIS.

The BIS doesn’t spell out these costs in its latest report.

However, in a 2016 blog, Marilyn Tolle of the Bank of England’s monetary policy unit noted the potentially revolutionary impact on central banking that a CBDC could herald.

“CB coin [digital coin] issuance could have far-reaching consequences for commercial and central banking – divorcing payments from private bank deposits and even putting an end to banks’ ability to create money,” said Tolle.

“By redefining the architecture of payment systems, CB coin could thus challenge fractional reserve banking and reshape the conduct of monetary policy,” she said.

In its new report, the BIS points out that emerging market economies may leapfrog developed market central banks by introducing CBDC first.

“Those that do see clear benefits [in CBDC] are predominantly from emerging market jurisdictions,” says the BIS.

“This seems to be because financial inclusion projects create a clear mandate for central bank action, and a lack of current infrastructure limits the disruption a CBDC could create while simultaneously encouraging the use of new technology.”

As central banks dither over the introduction of digital currencies, a wave of experimentation with new payment technology continues in the private sector.

In many parts of the world, challenger banks or non-banks using mobile technology are gaining market share by offering cheaper domestic payments and international transfers.

Over 100 so-called stablecoins have now been launched. By aiming to track the market value of fiat currencies while offering immediate settlement and traceability, stablecoins perform the role of a retail-focused CBDC, but without a central bank guarantee.

And projects such as Clearmatics’ Utility Settlement Coin (USC) aim to introduce digital tokens for use in institutional financial settlement. Clearmatics is backed by a consortium of banks.

Such wholesale digital tokens, if successful, would pose a direct threat to central banks’ monopoly role in managing settlement accounts.

Want to stay up to date with the latest content from New Money Review? Sign up here.