Money, identity and privacy are all linked. But these concepts are constantly changing in the face of new technology.

Should money be anonymous or tied to the identity of the parties to a financial transaction? In an age where our online identities carry real monetary value, who should have the right to exploit the data trails we leave? And what does privacy mean when our movements and even our psychological reactions can be tracked?

In a three-part series, New Money Review examines these complex and evolving questions in detail. We start with the first two ideas—money and identity.

From Sumer to SWIFT—how identity rules confer power

Whether money should reflect identity is a hugely political question. This is because linking money to an owner confers great power on those who register and store the information.

In Sumer, the earliest civilisation of ancient Mesopotamia, writing developed as a form of accounting.

An identity system can be used to wield economic and political power

Initially, clay tokens were used to record debts, with the shape of tokens designed to represent a particular kind of obligation: cones, spheres and flat disks were measures of grain; ovoids were jars of oil; cylinders meant a sheep or goat; pyramids a person-day of work.

A system of recording debts as easy-to-forge tokens had obvious disadvantages. So the Sumerians came up with the idea of enclosing the tokens representing the debt in a clay envelope (or ‘bulla’): not a foolproof anti-forgery mechanism, but one which makes cheating a bit harder.

To help remind people what the debt was about, the tokens enclosed in the bulla were also used to make imprints on the bulla’s surface.

Sumerian bulla and clay tokens

From the clay bulla it was a short step to an abstracted form of writing on clay tablets. Using a reed or wood stylus, the authors of cuneiform, humanity’s earliest written language, started to record more complex commercial transactions, as well as legal contracts and administrative rules. At some point, the details of the parties to a transaction started to appear on clay tablets as well.

In recognition of the powers associated with the ability to record contracts, being a scribe in Sumer was a profession taught from an early age, and carrying exalted status. Over 70% of cuneiform scribes were the children of the aristocracy.

Five thousand years later, a current-day example provides more evidence of how an information and identity system can be used to wield economic and political power.

The US dollar still has de facto reserve status

SWIFT, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications, is an encrypted messaging network that helps financial institutions transmit information to each other securely. The messaging service is used to send payment orders, which are then settled by banks in the correspondent accounts they hold with each other.

But last week SWIFT said it was suspending some Iranian banks’ access to its system, effectively depriving the banks of the ability to send or receive money outside the country, and putting a stranglehold on Iran’s cross-border trade.

A week earlier US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin had warned SWIFT to disconnect any targeted Iranian banks ‘as soon as technologically feasible to avoid sanctions exposure’, warning SWIFT that the US would ‘aggressively’ use its authority to ensure compliance.

SWIFT advertises itself as a Belgian cooperative society, owned and controlled by its shareholders. So how, in practice, can the US government dictate its political will to banks in the other 200-plus countries that use the network?

The answer to that question lies in the continuing importance of the US dollar in the global financial system. Although the dollar lost its convertibility into gold nearly fifty years ago, it still has de facto reserve status. Over half of international payment flows by value are denominated in the US currency.

All US dollar transactions ultimately cross the books of the US central bank, the Federal Reserve. And if you wish to route a dollar payment via a bank that doesn’t have an account at the Fed, your bank needs to have an account with a US bank that does. But US banks also have to comply with rules set by the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control.

This administers and enforces sanctions against ‘targeted foreign countries and regimes, terrorists, international narcotics traffickers, those engaged in activities related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and other threats to the national security, foreign policy or economy of the US’.

Although the US Treasury’s rules don’t affect them directly, the European (and other global) banks that participate in SWIFT have been forced to toe the US line on Iran as a result of Washington’s extra-territorial reach: in effect, they have to respect the sanctions rules or face the loss of their own US dollar business (and risk punitive fines).

For example, in 2014, French bank BNP Paribas lost its licence to clear dollar-denominated transactions in energy trade finance for the whole of 2015 as part of a punishment for violating US sanctions against Sudan, Cuba and Iran. BNP also had to cough up a fine of nearly $9bn to the US government.

Both in ancient Sumer and the modern interbank system, the technology tying money to identity clearly has enormous worth. But what if the form taken by money prevents this link from being established in the first place?

The fight over registration

Certain types of money—and of assets that can easily be converted into money, such as shares and bonds—are not linked to any specific identity. Instead, anyone who has possession of them has the ability to spend or redeem them.

Sumerian clay tokens, cowrie shells, bank notes, a cheque with a blank endorsement, gold and silver bullion and cryptocurrencies are all examples of so-called bearer assets.

Illustrating the importance of payment to bearer, this promise is made explicit on banknotes to help reinforce the idea of transferability.

Bearer promise on UK £20 note

But many forms of money are registered in the name of the owner or creditor. Once Sumerian clay tokens gave way to bulla and eventually to clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform writing, money moved from bearer to registered form: the details of the creditor were recorded on the tablet.

The huge stone wheels (‘Rai stones’) that were used for centuries as money on the island of Yap in Micronesia are an unusual example of registered assets, since their registration was oral, rather than being recorded in writing (for example, chiselled on the disks themselves). But Rai stones had an implicit link to their owners, all the same.

In the words of one account, “stealing [Rai stones] was pointless: if the transaction wasn’t officially recorded in the oral history of the island, it still belonged to its old owner. The person that owned it needed to announce that he no longer possessed the stone and passed it on to another.”

The ownership of assets in the $250tn global debt market and the $50tn global equity market is recorded largely via registration, either on the books of central securities depositaries (CSDs) or via intermediaries such as custodian banks.

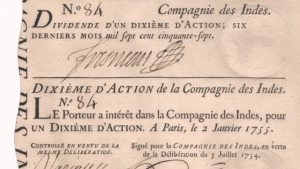

But not all shares and bonds are registered to individual owners. There’s a long (and ongoing) tradition of issuing these financial assets in bearer form.

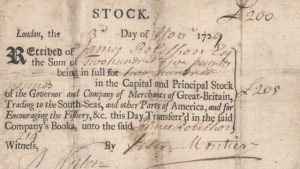

Two 18th century companies, both the focus of historic speculative bubbles, illustrate the different modes of ownership. Shares in France’s Compagnie des Indes were issued in bearer form, while shares in England’s South Sea Company were registered in the name of the purchaser.

A bearer share in the Compagnie des Indes

A registered share in the South Sea Company

“Blairmore’s true owners were kept hidden from view.”

Bearer shares haven’t gone away. They featured prominently in the 2016 Panama Papers leaks, with many of the world’s super-rich apparently using anonymised share certificates for decades to disguise the ownership of offshore companies.

According to the BBC, reporting on the leaks, the offshore wealth management company Blairmore, of which former UK Prime Minister David Cameron’s father was a director, used a bearer share structure to run its business.

“Blairmore company documents record how two employees of a bank in the Bahamas were holders of ‘2,347,280 shares in bearer form’ in 2005. This made them the official owners of all Blairmore’s investments,” the BBC reported, adding that “using bearer shares in this way ensured that the true owners—the wealthy investors in Blairmore Holdings—were kept hidden from view.”

Ironically, a year earlier, while Cameron was still prime minister, the UK had outlawed the issue of bearer shares by UK companies, citing concerns over illegal activities.

But the push to eliminate bearer shares still has a way to go. According to a 2016 report from the European CSD Association, registration of ownership was mandatory for shares in only around half of 38 European markets surveyed, while for bonds it was mandatory in only around a third of European markets.

A new challenge

As governments seek to crack down and enforce links between financial assets and identity, and as cash seems to be disappearing of its own accord, a new challenge is emerging.

Cryptocurrencies promise pseudonymity or even full anonymity to their users, a proposition backed up by sophisticated and apparently unbreakable mathematical functions.

In the third article of this three-part series we will look at the intensifying battle between governments and cryptocurrency proponents over privacy. But before then, in the second article of the series we’ll examine how concepts of identity have undergone a radical revision in the internet age.

Want to stay up to date with the latest content from New Money Review? Sign up here.