Settlement of securities trades matters. The world’s market for shares and bonds is now worth $150trn, almost double the $90trn global money supply. The keeping of accurate accounts of securities ownership and the smooth processing of buy and sell orders are pivotal to the orderly functioning of the 21st century economy.

But new technologies are shaking up the cosy world of the custodian banks and securities depositaries at the heart of the post-trade infrastructure—threatening many vested interests.

Faster trades, lagging records

In 1850 a previously unsuccessful businessman, Julius de Reuter, worked out a way to transmit financial market information more quickly between Paris and Berlin.

While the Berlin-Aachen and Paris-Brussels telegraph lines had already been built, there was a 145km gap between their end points.

de Reuter used carrier pigeons to fly between Aachen and Brussels, which was a ten-hour journey by land.

Clients of his ‘correspondence bureau’ proved willing to pay handsomely to receive price-sensitive information from the Paris and Berlin bourses in advance of their rivals.

de Reuter’s informational advantage disappeared in a matter of months as the rapidly expanding telegraph network filled in geographical gaps. But his initiative helped earn him enough capital to build a new business called the Reuters news agency.

the record-keeping part of securities transactions is stuck in the Stone Age

For traders, so-called ‘latency’ in electronic systems—the time lag from the transmission to the receipt of market data—is now measured in microseconds, rather than hours or days.

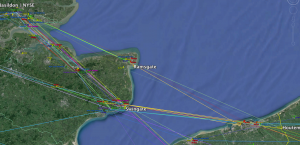

In recent years high-frequency trading (HFT) firms have battled to minimise the time taken to relay data between trading centres in continental Europe and the UK, studding the skyline in Calais, Dunkerque, Ramsgate and Dover with their microwave masts and antennae.

HFT microwave networks between England and France

Source: Sniper in Mahwah blog

But while the technological arms race in trading is now running into constraints set by the laws of physics, the record-keeping part of securities transactions is stuck in the Stone Age: the settlement of deals remains dependent on a slow, complex and costly infrastructure.

Most share and bond trades are settled—their ownership changes hands in exchange for payment—only two days after the trade date. And multiple intermediaries—clearing houses, securities depositaries, transfer agents, registrars, collateral managers, custodians—stand between the issuer of a share or bond and the end-investor.

The collective costs of these intermediaries are estimated to reach US$20-50bn a year, according to the Bank of England, amounting to a direct tax on investors.

Given recent advances in trading technology, it may be hard to grasp why the securities settlement infrastructure cannot be replaced at one fell swoop by something much faster and more efficient.

But past crises explain why many changes in post-trade networks have tended to happen slowly, if at all. And that glacial pace of progress means that incumbent institutions are hard to dislodge.

Settlement in paper

In the old world of paper certificates of stock or bond ownership, a time lag between dealing and settlement (the transfer of ownership in exchange for cash) was inevitable: certificates needed to be moved physically from seller to buyer.

Those responsible for running financial centres were clearly sensitive to the risk of settlement problems. Rules, formal or otherwise, could be put in place to make sure that the sellers of securities were paid on time.

Account-based settlement allowed unlimited free speculation

One practice was to settle stock trades relatively infrequently. For nearly two hundred years until 1994, settlement of trades in UK stocks followed a fortnightly ‘account’ system: any purchases during a two-week account period would be paid for six working days after its end.

This allowed the buyer of a share on the first day of a new account period over three weeks before having to hand over cash. It also granted unlimited free speculation—no money up front—to those wishing to go long or short for a week or two only.

The UK regulator, sensitive to the risk that a counterparty might not pay up, triggering a cascade of settlement failures, eliminated the account system in 1994.

Initially, UK share settlement switched to a ten-day rolling settlement cycle. That lag between trade and settlement was then shortened progressively to five, three and now two days, a settlement period now common in most major share and bond markets.

Limiting geographical distances also helped in minimising past paper settlement problems. The London Stock Exchange used to insist that member firms keep an office within seven hundred yards of the exchange itself. This helped speed up stock transfers by shortening the route of the messenger boys who carried cheques, share and bond certificates from one bank vault to another.

But during boom times, especially those involving cross-border trading, there was always a risk that exuberance in trading would run ahead of the capacity of banks’ back offices to handle the resulting flood of paper.

The New York paper crisis

In the 1960s, a new ‘eurobond’ market sprang up in London, helping governments and corporations raise funds relatively cheaply by tapping into a European pool of dollar-denominated savings. The owners of these dollars were reluctant to repatriate them to the US, where interest rates on deposit accounts were capped.

But while the issuance and trading of eurobonds—which were issued as paper certificates, with detachable interest coupons—took place outside the US, their settlement and custody was in the hands of New York-based firms. US banks had a monopoly on dollar transfers, the payment part of the settlement process.

Rapidly rising activity levels in the new debt market soon caused the movement of paper certificates to grind to a near-standstill.

According to Peter Norman, a former Financial Times journalist and author, the smooth running of the eurobond market was not helped by the fact that trading firms and their post-trade counterparts were separated by the Atlantic Ocean, at a time when telecommunications were expensive.

“Nothing was regulated: believe me, anything went”

But foul play also played a part in separating bonds’ owners from the records of their ownership.

“In an unregulated market, customers were sometimes cheated by banks which cynically exploited the inefficiencies of the settlement infrastructure for their own ends,” writes Norman in his account of the securities industry, ‘Plumbers and Visionaries’.

“It was not unknown for banks deliberately to hold on to bonds they had already been paid for, even deliver them on to some other counterparty, and collect funds a second time.”

Stanley Ross, a leading eurobond trader at the time, recalled what he and his counterparts got up to during a 2013 speech to the International Capital Markets Association.

“Nothing was regulated: believe me, anything went,” said Ross.

“Want to raise some cash? Easy, short some new eurobonds. Payment on value date [usually seven days after the trade date—New Money Review comment], delivery in due course.”

“This led to many firms not delivering some bonds for one or two years,” said Ross.

“Not only did they use the clients’ money all that time, but much worse, when bonds did finally come, it was not unusual for them to cut off all the available coupons before delivering on.”

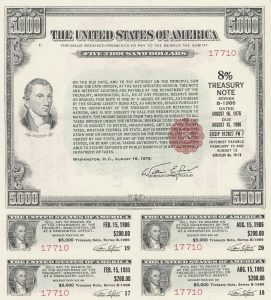

Heightening the risk of theft, many bonds, US Treasuries included, were then issued in bearer form. In bearer (as opposed to registered) financial assets, possession confers ownership.

A 1976 bearer US Treasury bond

According to the New York Times, a witness told a US Senate subcommittee in 1971 that the scale of the post-trade settlement problems on Wall Street had been so great that the Mafia had turned the US financial market into a ‘free-for-all’ in stolen securities.

From paper records to dematerialisation

The immediate response to the late 1960s New York settlement crisis was a move to ‘dematerialisation’. This means the issuance of shares or bonds not as paper certificates but as records, usually electronic, in ledgers managed by a securities depositary or custodian.

dematerialisation solved one problem while creating another

The computerisation and centralisation of share ownership records at such trusted intermediaries has since taken place in practically every capital market.

But dematerialisation solved one problem while creating another, more dangerous one.

In the second article of this series, we show how, by eliminating the risk of a simple theft of securities, dematerialisation created a centralisation of risk at financial institutions. In time, this centralisation helped create a threat to the financial resources of whole countries.