An old adage says: “Don’t invest in what you don’t understand”. Many people interested in buying bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies have been put off by the apparent complexity of these new forms of money and the jargon involved in describing them. But cryptocurrencies don’t have to be inaccessible.

In a three-part series, we explain where cryptocurrencies came from, what powers their networks and how they are governed.

In this, the third and final article of the series, we examine the governance of cryptocurrencies.

Cryptocurrency governance is a tricky subject. There are different interest groups involved in the evolution of a network like bitcoin, often with overlapping functions.

First, there are the miners—the network nodes rewarded with new cryptocurrency tokens for processing transactions. Then there are the non-mining nodes, who also keep the currency’s transaction records. There are the core software developers, who have an outsized say in determining how a cryptocurrency’s code is maintained. And there are the coin owners, who can vote with their feet by adding to or selling their stakes.

And how can humans change the future of a cryptocurrency, anyway? In the second article of this series we explained how bitcoin’s blockchain extends automatically through time, since the “longest chain” rule ensures consensus across the network.

The idea that cryptocurrencies are immune to human intervention is clearly a myth.

Put another way, the nodes participating in bitcoin’s network don’t have to make a value judgement about the currency’s transaction history—they just follow the longest version of it.

This apparently self-guiding nature of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies may be hard to accept for those accustomed to the way traditional currencies operate.

Fiat currencies like the US dollar, euro, pound or yen are under the notional control of a central bank, usually backed by a government mandate. Via interest rates, bank capital and liquidity requirements and sometimes exceptional measures like quantitative easing, central banks control the volume of money in the economy and its cost.

By contrast, in the words of Bloomberg columnist Elaine Ou, “the idea that a $160 billion cryptocurrency is controlled by a software protocol running on autopilot is discomfiting to some.”

But, on a longer timescale and at a deeper level, the idea that cryptocurrencies are immune to human intervention is clearly a myth.

There are often vocal disagreements between cryptocurrency advocates, reminiscent of the schisms typical of the early stages of a new religion.

By contrast with the secretive discussions of central bankers, cryptocurrency arguments are played out in public, sometimes involving inflammatory language and even threats of violence. Behind-the-scenes meetings between network members do take place and decisions taken at these meetings can influence the future of individual currencies.

So how do cryptocurrencies handle differences of opinion between network participants, whether miners, nodes, software developers or coin holders? There are two important ways in which those participants are able to modify the original currency design.

What makes a blockchain valuable is human consensus.

Altcoins

Satoshi Nakamoto’s white paper tells us that bitcoin was designed to serve as a new form of money (specifically, he/she/they labelled it “a peer-to-peer electronic cash system”). But inherent in bitcoin’s design are certain limitations.

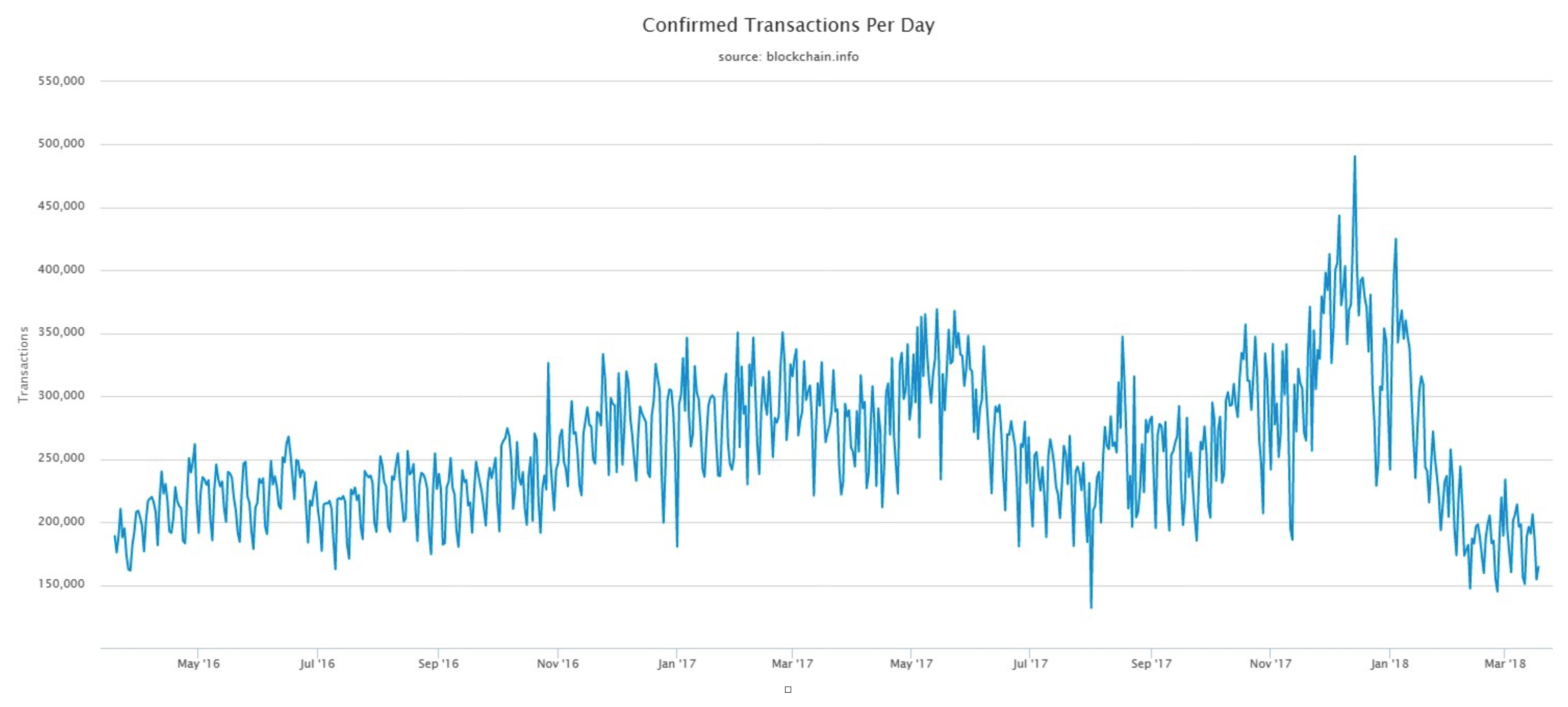

First, a self-imposed limit on the size of an individual block meant the bitcoin network can’t handle more than a maximum of seven transactions per second (around 600,000 per day), significantly less than most centralised payment systems. Confirmed transactions on the bitcoin network have been running at around half this theoretical limit during the last two years.

Confirmed transactions per day on bitcoin network

Source: blockchain.info

Second, bitcoin has limited uses apart from serving as money. In theory, it could be used to record other types of information than transactions in bitcoin itself: the software has its own programming (or “scripting”) language, allowing bitcoin miners to add additional information to blocks.

But this is subject to a size limit of 40 bytes per block (a byte is the smallest unit of computer memory in most programming languages). This makes bitcoin unsuitable for a broader range of record-keeping functions, such as property transfers, notarial functions or proofs of personal identity.

Some information “tags” have been added to individual bitcoin blocks, nevertheless: most famously, Satoshi Nakamoto stamped a message into bitcoin’s first block saying “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks”.

Third, bitcoin’s pseudonymous character made the currency unsuitable for those seeking complete anonymity. Once an individual or an organisation is linked to a particular bitcoin address, the whole transaction history of that entity becomes clear for all to see. Some cryptocurrency advocates would prefer stronger encryption to keep the prying eyes of government agencies away from their financial dealings altogether.

Many of the 1500-plus cryptocurrencies now in existence, often described as “altcoins”, can best be understood as variants on bitcoin, aimed at addressing some of the constraints built into bitcoin’s software protocol. Some currencies, like litecoin, launched in 2011, were a “fork” of the bitcoin network: others, like ethereum, launched in 2015, held a crowdsale to raise their starting capital.

Litecoin can handle a higher number of transactions per second than bitcoin thanks to its faster rate of generation of blocks: litecoin’s blocks arrive around every two and a half minutes, compared to bitcoin’s ten. A trade-off for litecoin users is that the network has considerably less processing power behind it than bitcoin, reducing its overall level of security.

Ethereum was designed primarily to overcome the constraints inherent in bitcoin’s scripting language: instead, ethereum allows for a fully-featured programming language to be run on its blockchain.

This makes the ethereum network more suitable for a broader range of record-keeping functions than the bitcoin blockchain. However, adding complexity to the protocol makes ethereum theoretically less secure than bitcoin.

And cryptocurrencies like Monero, Dash and Zcash use different cryptographic functions than bitcoin to help obscure transaction histories, making them the cryptocurrencies of choice for those seeking anonymity. However, these currencies’ networks are more centralised than that of bitcoin.

Forks

Differences of opinion about a cryptocurrency can be handled in a rough and ready way by a process called soft forking

Many differences of opinion about a cryptocurrency can be handled in a rough and ready way by a process called soft forking. This means an alteration to the currency’s software rules that recognises earlier blocks—those produced under the pre-change rules—as valid. If a majority of miners adopt the altered software, other network nodes are then likely to fall in line.

Bitcoin has undergone a number of such soft forks, many aimed at improving the operation of the software underlying the currency. These are ordered as bitcoin improvement protocols or “BIPs”.

However, sometimes differences of opinion about the future direction of a cryptocurrency are irreconcilable, resulting in a hard fork. A hard fork means a change to the rules of the network so that the software enforcing the old rules will not recognise blocks adhering to the new rules. Effectively, the network splits into directly competing versions of the same currency.

On 1 August 2017, for example, bitcoin divided into two via such a hard fork, leaving holders of the original bitcoin (BTC) tokens with an equivalent number of bitcoin cash (BCH) units.

The key change to the bitcoin protocol brought about by bitcoin cash was an increase in the currency’s block size from one to eight megabytes. This meant individual blocks could store more transaction data, in theory making the currency more suitable as a means of payment.

Supporters of the traditional, 1 megabyte block size argued that the block increase in bitcoin cash would increase the likelihood of the cryptocurrency running into longer-term capacity problems, since it would become more expensive over time for nodes to keep a record of transaction data. This, in turn, risked bitcoin cash’s miner network becoming more centralised and less, traditionalists said.

Supporters of bitcoin cash control the bitcoin.com domain and the bitcoin twitter feed

The disagreements between these two camps have been played out in public, with supporters of each side making allegations of dirty tricks. Supporters of bitcoin cash control the bitcoin.com domain and the bitcoin twitter feed and have used them to promote BCH as the “real” version of the cryptocurrency. Critics allege that those promoting the newer version of the currency are deliberately misleading people through confusing branding.

Cryptocurrency ethereum underwent a hard fork in 2016, although for different reasons than the 2017 bitcoin cash hard fork: an investment fund built on top of the ethereum blockchain had suffered a theft of assets, leading to a dramatic fall in the market value of ethereum itself.

A group of influential software developers was able to obtain majority support amongst ethereum coinholders for a retroactive forking of the currency, effectively restoring holdings to the state before the theft took place.

However, several ethereum holders disagreed with the idea of making retroactive changes to the currency’s blockchain, arguing that this went against the principles of immutability and decentralisation that are often advertised as central features of cryptocurrencies.

As a result, ethereum split in July 2016 into two versions: ethereum classic (ETC), representing those rejecting the change of transaction history, and ethereum (ETH), representing those accepting the change.

“We are witnessing one of the greatest and most fascinating competitions of technology and money ever.”

The value question

Some critics of cryptocurrency regard the ability of these software protocols to mutate and split as a version of the past practice of clipping or shaving gold and silver coins—effectively, as inflation.

According to Agustin Carstens, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), while bitcoin’s money supply may be capped, the supply of forks and altcoins is not.

“We may be seeing the modern-day equivalent of clipping and culling [of coins],” said Carstens in February.

Clipped coins

Source: the Journal of Ancient Numismatics

“In bitcoin, these take the form of forks, a type of spin-off in which developers clone Bitcoin’s software, release it with a new name and a new coin, after possibly adding a few new features or tinkering with the algorithms’ parameters.”

“Forks can fork again, and many more could happen,” said Carstens.

“After all, it just takes a bunch of smart programmers and a catchy name. As in the past, these modern-day clippings dilute the value of existing ones, to the extent such cryptocurrencies have any economic value at all.”

Others dispute that the ability of a cryptocurrency to fork necessarily results in a dilution of overall value.

“What makes a blockchain valuable is human consensus, a widely held belief that creating machine consensus according to a certain set of rules is useful,” says ethereum developer Zsolt Felföldi.

One investor in cryptocurrencies regards the open source nature of the underlying protocols as a strength.

“Anybody can fork the protocol, perform their desired changes and attempt to build value and a community around it,” Spencer Bogart, partner at Blockchain Capital, wrote in a Medium article earlier this year.

“I see bitcoin and bitcoin cash each pursuing their own paths as a net gain for the community as a whole. It’s very possible that there’s a real place in the market for both.”

“Ultimately, we are witnessing in real time one of the greatest and most fascinating competitions of technology and money ever.”

If I understand correctly, Bitcoin cannot be forked so easily; at least 75% of nodes need to signal their approval for the implementation of a BIP (Bitcoin Improvement Protocol). Given sufficient signaled approval, the network will then try to adopt the new rule(s), but only if 95% of nodes follow. If successful, the value of the remaining chain (maximum 5%) would be rather small, and therefore less valuable. High hurdles for change and high incentive to be with the main chain are meant to make rogue forks difficult as well as keep the consensus on the same chain.