Judging by the volume and the heat of the headlines they generate, cryptocurrencies touch something deep in the human psyche. But the contradictory nature of those headlines may leave you with a headache.

Depending on who you listen to, bitcoin is a form of artificial intelligence and cryptocurrencies are the future of money. Or bitcoin isn’t any such thing. Bitcoin is a bubble. It’s for drug dealers, pornographers and other criminals. Bitcoin is a protocol. It’s a virus. Bitcoin is a political ideology. Cryptocurrencies are subversive. Bitcoin squanders energy, or it’s a clever use of energy that’s too hard to store. It’s a terrorist’s dream come true. Perhaps it’s for young males, and particularly those on the autistic spectrum. Bitcoin is a fraud: it’s for murderers. Bitcoin is a complex network. Cryptocurrencies are a cult.

Perhaps the polemics are unsurprising: apart from religion, no other subject generates such noisy and partisan debate as money.

We don’t need to take sides in the debate to accept that our concept of money has mutated throughout history: it’s taken many different forms and, collectively, we’ve shifted frequently from one version to another.

There’s nothing immutable about the current, post-Bretton Woods era of unbacked fiat currencies, a period that has lasted less than fifty years (US President Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility into gold in 1971).

Are we seeing a seismic shift in the form of money, so that we end up with a new store of value, medium of exchange, unit of account and means of payment? Or could we see competing, overlapping versions of these functions?

Apart from religion, no other subject generates such noisy and partisan debate as money.

One of the main features of cryptocurrencies is their immutable, transparent ledger of past transactions, called a blockchain. Tradeable tokens of the currency have value because they represent a share in the ledger. But is this truly an innovation?

The inhabitants of the island of Yap in Micronesia used stone money in a similar way for centuries. No-one shifted the so-called Rai stones around when a transaction was made: instead, people transferred notional mental shares in the immovable, imperishable discs.

Although all money relies on shared acceptance across a network of users that certain underlying objects have value, Rai stones took this concept to an extreme.

Underlining the abstract nature of many forms of money, the practice of transferring shares in Rai stones could continue even when the stones were lost overboard from ships and rested at the bottom of the sea.

Rai stones

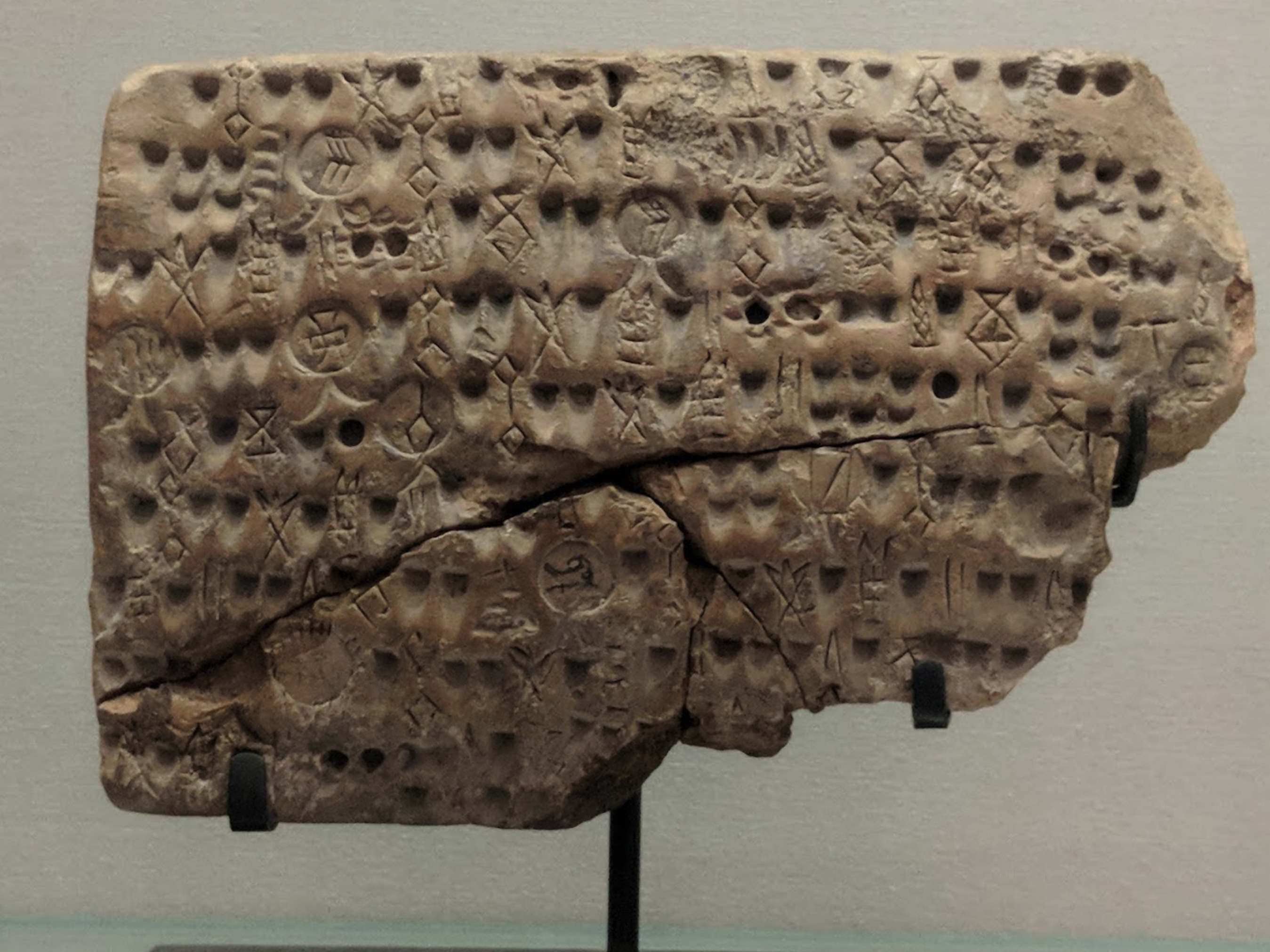

Another form of money, the clay tablets of Mesopotamia, were also an immobilised ledger of accounts.

Mesopotamian clay tablet

Many people seem to have difficulty accepting cryptocurrencies as real because they can’t touch them or hold them in their hand, like you could a silver “owl” of Athens, one popular currency of the ancient world.

Athenian silver “owl”

But Rai stones show that transferability in physical form is not a prerequisite of a functioning store of value or unit of account.

Rai stones were local money: they worked for a community of perhaps tens or hundreds of thousands of people. Within that size of community, everyone trusted each other to keep the correct score of ownership. What is undoubtedly new with cryptocurrencies is the massively greater scale at which the principle of network money is now being applied. In turn, this relies on faith in the underlying technology.

As is often the case with money, value and utility rest on a circularity of argument. Rai stones were valuable because they were accepted. But they were also accepted because they were valuable.

Those criticising bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies for having no inherent value perhaps haven’t thought long and hard enough about this aspect of monetary history. In effect, the fact that bitcoin was originally “bootstrapped” into existence in early 2009 by a small group of computer scientists doesn’t necessarily invalidate it as money.

The fact that bitcoin was originally ‘bootstrapped’ into existence by a small group of computer scientists doesn’t necessarily invalidate it as money.

Another objection to cryptocurrencies comes from the position of those in power—the priesthood of the existing belief system. In one sense, the vocal recent criticisms of bitcoin from central bankers and heads of commercial banks are surprising.

By comparison with the existing monetary system, cryptocurrencies are still tiny in terms of their market value and the scale of their adoption. But at the same time the bankers are surely right in their gut instinct that the two systems of money are essentially contradictory, and that the new version threatens the old.

How to counter the threat? Central banks have been discussing the introduction of their own cryptocurrencies, but are acutely aware of the risk that allowing the public to stake direct claims on the central bank’s balance sheet could undermine trust in the broader banking system.

If your sterling, euro or dollar bank deposits can be replaced by an account at the Bank of England, Fed or ECB, why wouldn’t you want that?

“A general purpose central bank digital currency could give rise to higher instability of commercial bank deposit funding,” the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) wrote in a report released in March 2018.

“Even if designed primarily with payment purposes in mind, in periods of stress a flight towards the central bank may occur on a fast and large scale.”

Many governments, especially those who have mismanaged their national currencies, will not welcome competition.

The emergence of cryptocurrencies could also signal a more fundamental shift in global power structures. It’s unsurprising that three of the countries under US-led financial sanctions are taking a close interest in the technology. North Korea is reportedly trying to amass a cryptocurrency war chest, Venezuela has started its own cryptocurrency and Iran may follow suit.

There may well be a final showdown ahead between the proponents of government-issued fiat currencies and supporters of new currencies based on cryptography. After all, the history of money is full both of threats of violence and of actual violence.

Those caught clipping (debasing) coins in 18th century Britain faced the death penalty: devaluing the currency was the privilege of kings. Possession of foreign currency in the USSR was a criminal offence, liable to land you in a labour camp. Many governments, especially those who have mismanaged their national currencies, will not welcome competition. Nor will the bankers who have benefited from an effective monopoly.

But there is also a more peaceful potential outcome—where government and private currencies coexist, albeit in an uneasy relationship. If this period of competition is what lies ahead, all of us can benefit from freer thinking about the nature of money.

Some people argue that Bitcoin is undemocratic, since, if successful in replacing fiat, those who ‘joined’ last will pay the highest price when converting from fiat. While this is true, conversion from fiat is voluntary.

But how democratic is our current fiat currency system? The possibility of loss of savings via inflation and / or bank and / or government insolvency is real.

In fact, thinking about how fiat money is created reveals it’s biggest flaw: there is no creation of money without the simultaneous creation of debt. Let that sink in.

“Inside money”: a central bank can ‘print’ money. But as long as it remains inside the CB it’s not yet money. Coins and notes are being put into circulation as commercial banks acquire notes and coins from the CB. Not for free, of course, but by having the amount deducted from their account with the CB. The CB in turn account for ‘notes and coins in circulation’ under ‘liabilities”.

In Quatitative Easing, the Fed buys bonds from Primary Dealers, crediting their accounts with the Fed with the respective proceeds. This represents a liability for the Fed.

“Outside money”

When you apply for a loan at the bank, the bank credits your account with the requested sum. Your debt is now an asset for the bank (loans outstanding to customers). Accordingly, should you deposit cash in the bank, you have become a creditor to the bank, and your deposit shows up under “liabilities” in the bank’s balance sheet.

Same is true for shadow banking as well as off-shore banking. There simply is no creation of money without simultaneous creation of debt.

In aggregate, there is no debt-free saving.

If someone wants to save, someone else needs to go deeper into debt.

Our economy only grows while debt increases. Even a slow-down in the rate of growth of debt can lead to a financial crisis.

This leads, of course, to problems: debt cannot grow faster than the underlying assets supposed to earn interest to service said debt (or GDP). As (real) GDP growth can be broken down into population growth and productivity growth, it becomes clear that peaking populations as well as slowing productivity growth are putting natural limitations on the growth of debt.

Debt-free saving is offered, among other things, by gold and by Bitcoin. Neither a gold coin nor a Bitcoin is anybody else’s debt. Nobody can default on a gold coin or a Bitcoin. You could go as far as to say that debt will be impossible in a Bitcoin-based currency system. This would have vast implications for everything, from how governments are forced to run balanced budgets to sharing wealth as a society.