There’s no easy way to address the frictions affecting global money flows, says the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI), which looks after the safety and efficiency of the global financial system.

Cross-border payments costs weigh particularly heavily on the migrant workers sending remittances from higher-income countries to their families in lower-income countries.

Global remittance flows reached a record $554bn in 2019, according to the World Bank, although they are forecast to fall to $445bn this year as a result of the economic crisis caused by the coronavirus.

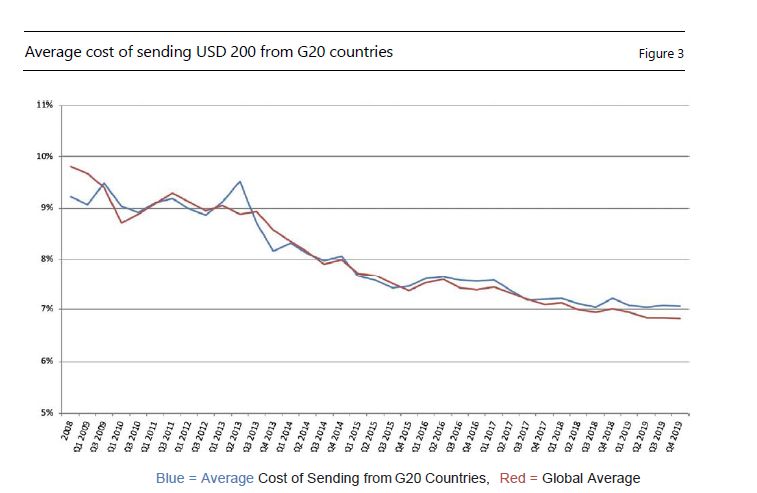

In 2009, the G8 leaders adopted a target of reducing the global average cost of sending international remittances from 10 percent to 5 percent within five years. In 2011, G20 leaders adopted the same target but pushed the deadline out to 2016.

But remittance costs have so far failed to fall to the desired levels.

“The rate of reduction has slowed in recent years and the global average cost of sending $200, at 6.82 percent in Q4 2019, remains well above the G20 commitment in 2011 to reduce the cost to 5 percent and the UN Sustainable Development Goal target of 3 percent by 2030,” the G20 Financial Stability Board admitted earlier this year.

Average cost of remittances

In a new report, the CPMI has set out what it sees as nineteen building blocks required to ease frictions in global money transfers.

“The building blocks start with a commitment from the public and private sectors to envision a better payments system,” said Sir Jon Cunliffe, chair of the CPMI and deputy governor of the Bank of England.

“They call for better coordination of national regulation, supervision and oversight arrangements. They include making improvements to existing infrastructure, such as improving the operating hours of payments systems, providing greater access and reducing the cost of the liquidity that participants have to maintain in the systems,” he said.

“There is no magic bullet.”

And the building blocks include better data processing rules, said Cunliffe, who pointed out that some national payments systems still rely on messaging standards developed for the era of the telegraph.

Other building blocks set out by the CPMI are new payment infrastructures, such as multilateral cross cross-border payment platforms, stablecoins and central bank digital currencies.

According to the CPMI chair, global cross-border payments amounted to some $20trn in 2019 and are estimated to reach $30trn by 2030.

But Cunliffe stressed that improving the global payments system is not just a question of better technology.

“This is not just a technological issue. There is no magic bullet. Improving cross-border payments is a many-sided challenge,” he said.

According to Cunliffe, the lack of progress on cross-border payment costs is also helping fuel demand for alternative transfer methods, some of which are largely out of the control of national governments.

“The shortcomings of the current system have been brought into sharper relief not just by the improvements we’ve seen in domestic payments, but also by the proponents of new technology solutions, such as cryptocurrencies and stablecoins, who rightly point to the failings of the current system as justification for their own schemes,” said Cunliffe.

The CMPI chair warned that failing to address the frictions in the global payments system will have a negative impact on economic development.

“The costs and hassle of making payments across border discourage businesses, and particularly small businesses, from entering the global marketplace,” said Cunliffe.

In its new report, the CPMI said that making cross-border payments cheaper and safer is a process likely to take years, and one which will involve complex planning.

“Some [of the nineteen building blocks] provide for early benefit realisation. With others, it will take years for benefits to materialise,” the CPMI said.

“The difficulties in determining which building blocks to advance in what order and their implementation should not be underestimated. Some require significant involvement of the private sector and/or additional international coordination, and the costs, technical complexity and associated risks differ between building blocks.”

Some of the proposed steps might prove particularly challenging for emerging market and developing economies, the CPMI said.

While payments systems in individual countries have become faster, safer and cheaper, it has not been possible simply to plug them all into each other.

Earlier this year, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), which hosts the CPMI, said that connecting different national payment systems into a single global network could give rise to complex legal issues.

And while there have so far been 23 attempts to link payment systems from different jurisdictions, 22 of these attempts have failed to attract significant volumes, the BIS said.

Sign up here for our monthly newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes