The global financial markets are now increasingly dependent on a single currency, the US dollar, and a single source of liquidity—the US central bank.

That’s the conclusion drawn by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in its annual economic report, published last week.

The BIS, which is owned by 62 central banks, acts as the main research and policymaking body for the global financial system. It also hosts the committees responsible for the world’s financial infrastructure.

According to the BIS, March’s coronavirus-inspired market panic exposed the fragility of the US dollar-based system. The BIS points out that the use of the dollar in financial contracts around the world has expanded dramatically during the last two decades.

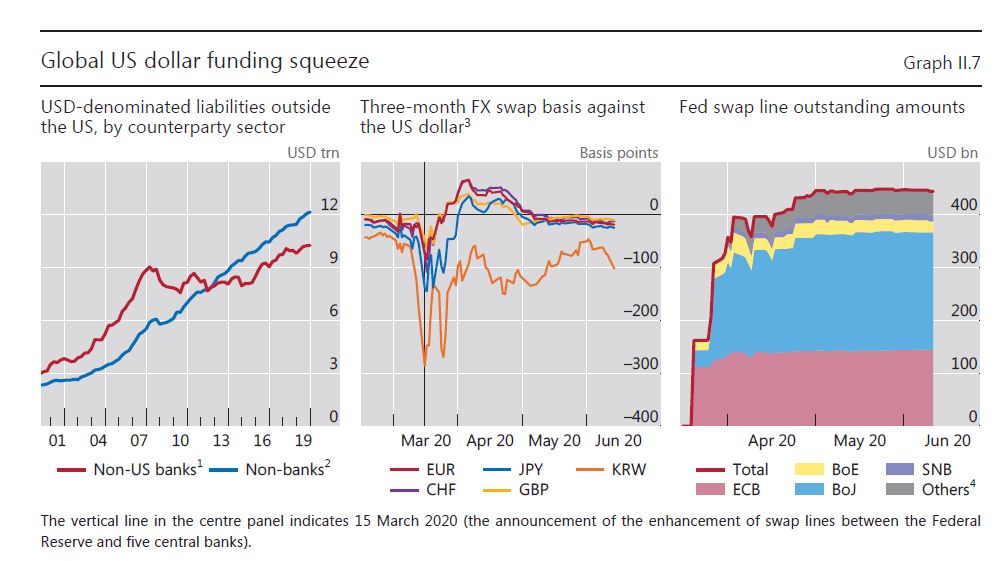

US dollar liabilities of non-US banks outside the US grew from about $3.5trn in 2000 to around $10.3trn by the end of 2019, the BIS calculates. For non-banks located outside the United States, they have grown even more rapidly and now stand at roughly $12trn, almost double what they were a decade ago.

“Investors’ de-risking led to a scramble for dollars”

This places the non-US borrowers of dollars in a precarious position, the BIS points out, since these entities cannot draw on their own dollar deposit base or raise funds in US markets in times of turbulence.

In such circumstances, said the BIS, foreign institutions with dollar liabilities are reliant on foreign exchange swap contracts to raise funding.

“During the Covid-19 crisis, just as during the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC), global investors’ rapid de-risking led to a scramble for dollars,” the BIS said in last week’s report.

“With bank funding under heavy pressure, possibly compounded by tighter risk constraints from the dollar appreciation, the supply of dollar funding dried up in many parts of the world.”

“As a result, cross-currency basis swaps—a barometer of the imbalance between demand and supply of dollar funding—widened significantly,” the BIS said.

During March, the three-month basis swap between several global currencies and the dollar widened dramatically, meaning that foreign borrowers were having to pay substantially more—up to 300 basis points extra for those using Korean Won—to raise dollar funds.

Source: BIS Annual Economic Report

The market dislocation also led to severe imbalances in the US Treasury market, the world’s largest government bond market, the BIS notes.

In March, long-dated treasuries were hit especially hard, with the spread between 30-year yields and corresponding interest swap rates widening dramatically, the BIS said in its report.

At the same time, large differences in yields between ‘on-the-run’ and ‘off-the-run’ bonds signalled a breakdown in the usual market arbitrage mechanisms. These market movements then caused a broader evaporation in liquidity.

“As volatility picked up and margin calls surged, liquidity in futures markets evaporated. Futures-implied yields dropped more rapidly than bond yields, causing mark-to-market losses for relative value investors who had sold futures and bought bonds,” the BIS said.

“To meet the margin calls, positions were rapidly unwound, notably by selling bonds to cover their short positions in futures. This pushed the prices of Treasuries lower (their yields higher), resulting in a ‘margin spiral’.”

“The market turbulence then spread more widely, including to the large class of hedge funds that follow rules-based investment strategies (so-called systematic funds),” the BIS said.

To alleviate the dollar funding pressures, on 15 March the Federal Reserve reinforced direct swap lines with five other global central banks and reopened them for another nine central banks.

The Fed also increased the amounts and maturities of its swap lines and made borrowing costs more favourable, the BIS said.

The growing dependence of the global financial system on the US is itself a source of instability

According to the BIS, this year’s market turbulence has reinforced the US central bank’s role at the centre of the global financial system.

“With the GFC as precursor, the role of the Federal Reserve as a global lender of last resort has been further cemented,” the BIS said.

Some central bankers have argued that the growing dependence of the global financial system on the US is itself a source of instability.

Last August, Mark Carney, the outgoing governor of the Bank of England, attacked US monetary hegemony in a speech at the annual Jackson Hole symposium of central bankers, held in Wyoming’s Rocky Mountains.

“The growing asymmetry at the heart of the international monetary and financial system is putting the global economy under increasing strain,” Carney said.

Carney cited evidence that the US currency punches above its weight, given the country’s role in the world’s economy.

The dollar is the unit of account in invoices worth five times more than the US’s share in world goods imports, Carney said, and three times the country’s share in world exports.

To address the problems he saw as caused by dollar dominance, Carney called for the introduction of a new multipolar currency system, based on a basket of currencies issued by participating countries.

Carney’s plans echo the global currency system envisaged by British economist John Maynard Keynes at the end of the Second World War.

Sign up here for our monthly newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes