Hard economic times can spur the adoption of local currencies. Could digital payments give a boost to the trend?

In an economic slump, no one has much cash. And if they have some, they hold on to it: when prices are falling, your dollar, pound, yen or euro will be worth more tomorrow than it is today.

But this attitude can then spread and become self-reinforcing, causing further economic damage as businesses fail and people retrench even further. It’s not without reason that governments and central bankers are so scared of deflation.

Combating deflation

In the depths of the 1930s depression, the last worldwide episode of falling prices, one Austrian community came up with an ingenious solution to the lack of circulation of money. It started its own currency.

In 1932 Wörgl, a city of 13,000 inhabitants in Austria’s picturesque Tyrol region, printed its own banknotes to try and stimulate the local economy.

The currency had an innovative feature, suited to the deflationary times. Holders had to ‘stamp’ it to keep it in circulation. The stamp—which was physically attached to each banknote—cost 1 percent of face value a month.

The Wörgl, with monthly stamps attached on the right

The result of this in-built depreciation—called ‘demurrage’—was that Wörgl money circulated over a hundred times faster than the national currency, the Austrian schilling. The rapid velocity of money stimulated the local economy and caused others to label the experiment ‘the Miracle of Wörgl’.

During the period of Wörgl money’s existence, the city managed to build new houses, a reservoir, a ski jump and a bridge while the rest of the country was mired in unemployment.

Gesell thought his monetary framework could address the injustices caused by inherited wealth and privilege

But Austria’s central bank stamped out the local currency project little more than a year after it had started, citing its monopoly right to print the country’s money. The Tyrolese city sank back into the global depression.

There was a political angle to the repression of the experiment, too. Wörgl’s so-called ‘stamp scrip’ design followed the ideas of radical German economist Silvio Gesell, who had died two years earlier.

Gesell saw broader benefits from a depreciating currency than just getting the local economy going and preventing hoarding.

He thought his monetary framework could address the injustices caused by inherited wealth and privilege, especially the concentration of economic resources amongst a few large landowners.

More modest in design

Gesell’s ideas live on, and in surprising places. Within recent years, his name has cropped up in speeches made by leaders of the US Federal Reserve, in the research papers of the International Monetary Fund and in the Financial Times.

But most local currency experiments undertaken since the Wörgl been more modest in design, aiming to complement rather than confront national money systems.

WIR bank, a Swiss initiative founded within two years of Wörgl’s stamp scrip, issues its own private money, called the WIR franc, which trades on a one-to-one basis against the Swiss franc, the national currency.

The WIR franc is accepted by local businesses in the hospitality, construction, manufacturing, retail and professional services, but is not redeemable against Swiss francs.

Brazil has a community currency called the ‘palma’, circulating in the Fortaleza region in the north-east of the country. The palma also trades on a one-to-one basis against the national currency, in this case the Brazilian real.

In contrast to the WIR franc, the palma is formally exchangeable into reals, a promise backed up by a reserve of real-denominated assets owned by a local community body.

This model—issuing a local money but backing it one-for-one by national units to ensure trust—is followed by a number of community currency initiatives.

For example, each Bristol Pound, a local currency for the Western English city, which has a population of around half a million people, is supported by a pound sterling in an account at a local credit union.

Bristol’s attempt to scale up

Diana Finch, Bristol Pound’s managing director, echoes Gesell’s warnings about the dangers of hoarding.

“Money is a store of value that accrues value the whole time you’re sitting on it,” she told New Money Review.

“That’s so counter-intuitive. There shouldn’t be a benefit to not using money. Every other store of value—whether grain, goods or a car—depreciates if it is left alone. For example, if you’re going to maintain a woodland and make sure it carries on being productive in a sustainable way, you’ve got to put work into it.”

“We couldn’t answer the question, ‘what’s in it for me?’”

But Finch admits that the Bristol Pound has failed to reach adequate scale since its launch in 2012. Earlier this year the project was close to shutting down after running short of funds.

“At its height, the Bristol Pound was used by about 700 businesses and 1300 individuals,” she told New Money Review. “Things then plateaued and dropped off.”

“It hasn’t worked, and we’ve learned a lot about why,” she added.

“It appealed to a tiny percentage of very woke people. But the average person has half an hour to do his or her shopping and prefers to go to Tesco rather than searching out three retailers that are members of the scheme and then paying over the odds in Bristol Pounds.”

“We couldn’t answer the question, ‘what’s in it for me?’,” she said.

Other community money projects based on a local version of the national currency have also failed to take off.

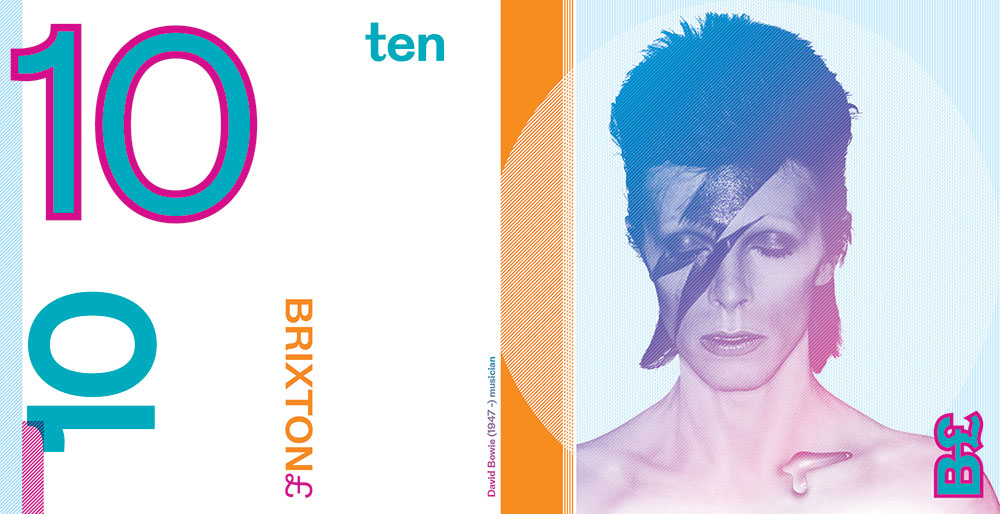

The Brixton pound, advertised as ‘the money that sticks to Brixton’, circulates only in the south London neighbourhood. The main distribution points for Brixton pounds are a café and a cash machine in the local market, while the notes are accepted at a small number of local businesses.

Brixton’s pound is better known for the artwork on its banknotes than for its usefulness as money.

David Bowie on a ten Brixton pound note

From pound to pay

But Finch and her Bristol-based colleagues haven’t given up.

Earlier this month Bristol Pound said it was shifting its approach from providing a complementary store of value to focusing on local payments.

“The plan is for Bristol Pay to become the preferred method of payment right across the city”

The non-profit company behind the scheme has entered into a partnership with e-wallet provider Payji to develop a new payment platform for the city, called Bristol Pay.

According to Finch, Bristol Pay will be able to operate at scale where the Bristol Pound couldn’t.

“The plan is for this e-wallet platform to become the preferred method of payment right across the city—big businesses, small businesses, everybody,” she told New Money Review.

“And as the platform is peer-to-peer—I will have an e-wallet in my name and so will the business I’m buying from—it should be much cheaper to run as there will be no external fees involved,” said Finch.

“Our idea is that for businesses it will be the cheapest form of payment,” she said, citing a potential transaction fee of 0.1-0.2 percent.

By comparison, when it launched, Bristol Pound charged businesses a relatively high fee—2 percent of transactions—for accepting the local currency in payments.

But the new payments platform is only half of the story.

To incentivise take-up of Bristol Pay, Finch and Payji plan to introduce a complementary local currency in the form of tokens, which will operate on the same e-wallet platform.

Bristol Pay’s tokens will not be exchangeable for sterling, but they will have some value, since they will be used to promote particular forms of economic activity.

“Tokens could be used for various purposes,” Finch told New Money Review.

“For example, they could be used to encourage individuals to do things in line with Bristol’s One City development plan, or to use local businesses. And businesses that collect tokens could obtain a discount on their rates (local taxes). We’ll be using tokens to develop a better economy,” Finch said.

According to Finch, the transaction data from the e-wallet will be used to build up profiles of local spending, but it will be used for the benefit of the local community, rather than being handed over to a large tech firm.

“The data from the money and the tokens will be held on one platform,” she said. “It can be used in an anonymised way to take a snapshot of how the local economy is working and to develop local policy initiatives, instead of being used for commercial gain by the likes of Google Pay.”

“It wasn’t a commercially viable proposition for venture capitalists, and it was too radical for the mainstream”

The idea of a local economy boosted by new currency in the form of native digital tokens is not new.

For example, the creators of Hull Coin, a community currency project started in 2014 in one of the UK’s most deprived areas, wanted to use a token-based incentive scheme to alleviate local poverty, rather than just introducing another version of the national currency.

Hull Coin, which was inspired by cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, was later abandoned after failing to achieve support from the UK’s National Lottery fund.

“Most local currencies are bought into existence—you exchange £50 for £50 of the local money, which then sticks to the local economy. The origins of Hull Coin were different,” Dave Shepherdson, the co-founder of Hull Coin, told New Money Review.

“Our idea was that if you did something to benefit people within your community, say local charities, the council or the health service, they would issue you with a credit that could be redeemed for a discount with local businesses,” he said.

“The Hull Coin scheme was a hybrid between a local currency and what I would call a social impact bond,” he said.

Shepherdson is frank about the failures of the scheme.

“Hull Coin was never designed to make money. It was designed within a public, civic context, to reduce poverty. It fell between two stools: it wasn’t a commercially viable proposition for venture capitalists, and it was too radical for the mainstream,” he said.

Local values

But the arguments for ‘smart money’ and its ability to represent local economic activity are more valid than ever, says technologist David Birch, who predicts that local currencies will play an unexpectedly important role in the money of the future.

“We will return to the multiple, overlapping community monies of the past”

“We will return to the multiple, overlapping community monies of the past but they will be smart monies, monies with values, monies that know about us,” Birch said in his 2017 book, ‘Before Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin’.

In a recent paper, Birch said that he expected communities—both geographically defined and virtual—to be one of the five groups that will be making digital money in the future (the other four, he predicts, will be commercial banks, central banks, cryptographers and companies).

Community-based ‘reputation money’ will operate under regulatory control and in a competitive market, Birch predicts.

The economic emergency resulting from the coronavirus pandemic may act as a catalyst for this trend.

According to Dutch research firm Sustainalytics, interest in local economies is likely to boom as a result of the disruption to global supply chains.

“While localised supply chains would likely increase manufacturing costs and prices for consumers, they could also bring material benefits in several areas,” Sustainalytics’ Bruce Jackson and Doug Morrow wrote in a recent blog.

“For example, they could lead to an increase in local jobs and tax revenues for governments. The carbon footprint of goods would be reduced, as components would not have to travel such great distances.”

“Tighter supply networks could also lead to better enforcement of supplier standards and enhanced product quality.”

Past community money experiments have tended to generate more publicity than impact. If that changed, it’s unclear how central banks and governments would react to their money-printing and tax collection rights being challenged at the local level.

But advances in technology and economic necessity appear to be setting up local currencies for a much bigger role in our everyday lives.

Keep up with New Money Review content: sign up here for our newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes