Global financial markets are now addicted to the trillions of dollars of liquidity being pumped into the system by central banks, says Michael Howell, CEO of CrossBorder Capital, a London-based advisory and fund management firm.

There is little prospect of central banks reversing course, says Howell, and we should look forward to further bouts of quantitative easing (QE) around the globe.

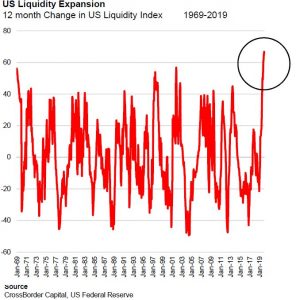

And, far from its previous promises to unwind the QE it embarked on after the 2008 crisis, the Fed has just overseen the biggest liquidity surge ever, CrossBorder Capital calculates.

Last year saw the biggest-ever US liquidity surge

Before setting up CrossBorder Capital in 1996, Howell, who is our guest on the latest New Money Review podcast, was research director at Salomon Brothers, the bond trading powerhouse of the 1980s and 1990s.

There are structural reasons why the wholesale money markets now depend on central bank support, Howell says.

“The financial system today is not so much about raising new money for new capital expenditure, which is what the textbooks tell you,” he says in the podcast.

“Instead, it’s much more about refinancing—the rolling over of existing debts. In order to refinance our whopping debt burdens, you need balance sheet capacity. And that’s what central banks provide.”

Meanwhile, banks have lost their role as the main creators of money, says Howell.

Instead, corporate cash pools, asset managers and sovereign wealth funds are now the main lenders in the financial system, and they are only prepared to lend against collateral, he says.

Central banks then play a crucial behind-the-scenes role by providing a liquidity backstop. They ensure that the collateralised (‘repo’) funding markets will continue to work: in other words, that lenders get their money back and that borrowers can roll over their positions.

It’s a “neat coincidence” that the latest round of QE has coincided with the start of the US election campaign, says Howell.

Michael Howell

But liquidity-driven booms all tend to end badly, says Howell, citing previous market crashes in 1973/74, 1987, 1989 (in Japan) and 2000. We should pay attention to rising bond yields or gold prices as a sign that this liquidity boom may be reaching its peak, he says.

And cryptocurrencies, which act as a store of value outside the current financial system, may have a huge role to play in future, argues Howell.

—highlights from the podcast—

Banks are no longer the primary creators of money

“Traditionally, money creation is the domain of banks. But the world has moved on a lot in the last 25 years and banks no longer play such a significant role. Money creation and credit creation are now much more the domain of the repo and wholesale money markets, which are critical in driving liquidity flows.”

What QE unwind? The Fed is loosening policy at the fastest rate ever seen

“Over the whole of 2019, the US saw the biggest annual increase in liquidity ever. If you look at things on a six-monthly basis, the increase in liquidity wasn’t quite as large as that following the 9/11 attacks or that following the 2008 crisis. But it’s still the third-largest liquidity increase ever.”

“It’s a very neat coincidence that the latest round of quantitative easing coincided with the start of the US election campaign.”

Central banks now underwrite all markets—and create asset price inflation

“The money markets are now very dependent on central banks. That’s because the whole mechanism of credit creation rests to a very large extent on repo markets. And the central banks play an important role in maintaining liquidity within those markets.”

“Too much money now creates asset price inflation, not high street inflation.”

Three main risks in the current system

“What are the main risks in the system? First, there’s a lot of debt to refinance. For that, you need balance sheet capacity, which is very much in the hands of the central banks.”

“Second, the polarity of the financial system has reversed in the last twenty years. The former borrowers are now lenders, and vice versa. Corporate institutional cash pools, like those run by Microsoft, Amazon and Google, require safe assets, but they can’t put their money into banks, and they need some kind of security. So they are heavily dependent on the collateralised finance markets. The problem here is that there is not enough safe collateral. The private sector is coming up with new debt instruments to serve as collateral, but some of these are of flaky quality. In an economic downturn, the value of this collateral could disappear and this would make the whole system more vulnerable.”

“The third risk is China, which is effectively a dollarised economy. The Chinese should be exporting yuan, but they are reexporting dollars and putting a lot of strain on the system. Initiatives like China’s ‘Belt and Road’ infrastructure programme, or the proposal to include the yuan in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR), are designed to reduce this dependency.”

Watch bonds, gold and bitcoin

“Bond markets are often a signal of trouble ahead. Bond yields haven’t climbed substantially yet, though I think they will. Another potential signal of concern would be a significant pick-up in the price of gold. But the dénouement could be 9 or 12 months away.”

“Cryptocurrencies have a huge role to play in this environment. If you have concerns about the integrity of monetary assets in the current system, stores of value like bitcoin should do extremely well. Bitcoin, like gold, is a liquidity-driven asset.”

Don’t miss any more New Money Review content: sign up here for our newsletter