Last week the general manager of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Agustín Carstens, made a spirited defence of central banks’ role in the global monetary system.

“The monetary and financial architecture needs solid foundations, just as a skyscraper does. And it is the central bank’s role to establish these foundations,” said Carstens.

One of the key public services provided by a central bank is its guarantee that a payment from one bank to another, if delivered across the central bank’s books, is irrevocable, said Carstens.

In a speech delivered at Princeton University, Carstens stressed that competing monetary systems, such as bitcoin, cannot ensure the finality of a payment in the same way.

“[In bitcoin], everything works by decentralised consensus, and what is deemed to be true is what the consensus says,” Carstens said.

“In such a system, if a sufficiently large group of bookkeepers collude to rewrite the history of the distributed ledger, payments that were made far in the past could be made null and void,” Carstens warned.

This kind of consensus scheme could have damaging knock-on effects on all economic activity, warned Carstens.

“You may think that you received a payment from a customer in the past, and had planned to serve other customers relying on the funds from that payment. But you might wake up one morning to find that the money you thought you had is no longer there. This simply cannot happen when the central bank is the final guarantor of finality.”

Cross-border settlement risk is increasing

As the BIS is sometimes called the central bankers’ central bank, its defence of these powerful institutions is unsurprising. But Carstens’ comments tell only part of the story.

Bitcoin’s consensus-based settlement approach reflects the fact that it operates on a global basis and without a central record-keeper. But central banks can only guarantee a payment within the individual currency areas that they control.

When it comes to cross-border financial flows, there is no final arbiter to determine when a payment becomes irrevocable.

And if the settlement of a foreign exchange (FX) transaction takes place at different points in time and space—say, between two banks operating in different time zones—new and complex risks arise.

In a famous case in 1974, the failure of a mid-sized German bank called Herstatt threatened to bring down the whole global financial system.

The German bank closed suddenly after risky FX bets went wrong. But the six-hour time lag between Frankfurt and New York left Herstatt’s American counterparties unable to collect the dollar payments they expected as part of these FX trades: by convention, FX trades are settled two days after transactions take place. The Herstatt default then led to a cascade of failed payments at banks around the world.

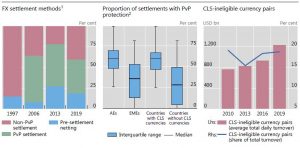

Over the following decades, central banks acted to try to reduce this kind of FX settlement risk. They encouraged the creation in 2002 of Continuous Linked Settlement (CLS), a specialist bank-owned institution that settles FX transactions on a so-called ‘payment-versus-payment’ (PvP) basis.

PvP eliminates FX settlement risk by ensuring that a payment in a currency occurs if and only if the payment in the other currency takes place, with CLS standing in the middle to monitor things.

But according to two of Carstens’ colleagues at the BIS, Morten Bech and Henry Holden, FX settlement risks are on the rise again, despite initiatives like CLS.

Writing in the latest BIS quarterly review, Bech and Holden warn that, partly as the result of a rise in FX market activity, a whopping $9trn of payments are now at risk on any given day.

And, worryingly, the proportion of all FX trades with PvP protection is now going down, falling from 50 percent in 2013 to 40 percent in 2019. This represents a reversal of the positive trend seen during the previous two decades.

FX settlement risk on the rise

Source: BIS

One reason for the recent increase in settlement risk is the greater proportion of emerging market currency trading in the global total, say Bech and Holden.

“Advanced economies settle a higher proportion of their FX with PvP protection than emerging market economies (EMEs), many of which have currencies that are not included in CLS,” they say.

Can supervisors arrest this worrying new trend?

“The task of reducing global risk is now firmly on the agenda of bank supervisors,” Bech and Holden say.

But, short of the introduction of a single global currency and a single institution to back it, there is no way to guarantee that cross-border payments cannot fail.

Or, cryptocurrency enthusiasts might argue—though this is heresy to the central bankers—we could consider a different, less risky type of cross-border settlement mechanism, one based on probability rather than irreversibility.

Don’t miss any more New Money Review content: sign up here for our newsletter