Last week, France’s finance minister slammed Libra, Facebook’s proposed payments coin, for encroaching on a key area of national power.

Bruno Le Maire said his country would block the development of the new digital currency as it represented a direct threat to monetary sovereignty.

But what is monetary sovereignty, and how is Facebook threatening it? Policymakers, it appears, are particularly worried about losing the income that accrues from making money.

What is monetary sovereignty?

According to Nobel prizewinner Robert Mundell, the right to make money is a test of any country’s independence and sovereignty.

Mundell says monetary sovereignty means three things in practice: the right to define the unit of account; the right to determine the means of payment (for example, governments may say you can only get rid of a debt by paying it off in one type of money, called legal tender); and the right to produce money.

Monetary sovereignty is a particularly important power when the face value of money exceeds its intrinsic, commodity value—if it has any.

Most national currencies are now created out of thin air. But even when money was backed by gold and silver, it could become overvalued.

For example, Lydia, which is the Western part of modern Turkey, was where metal money was invented in the seventh century BC.

“The earliest coins were made of electrum, a natural alloy of about 70 percent gold and 30 percent silver,” Mundell says.

“But hoards of the earliest coins found in the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus in 1904 contained ‘artificial’ electrum coins with much lower gold contents…as low as 30 percent,” he says.

“The Lydians and Greeks had not only learned how to use ancient Egyptian techniques of metallurgy, but also how to overvalue coins by using less of the more expensive metal.”

But performing a confidence trick on the users of money was a right that sovereigns kept to themselves.

Given the potential rewards at stake, rulers defined counterfeiting as an act of treason and used gruesome violence against offenders.

“Dominant countries have the least to gain by giving up monetary sovereignty”

In fact, monetary sovereignty explains much of political history. Gaining monetary freedom was a key ambition of the eighteenth-century American independence movement, for example. The US government eventually reached its goal, but only with difficulty.

“The US began as a colony, tried (but failed) to assert its monetary sovereignty; established monetary sovereignty for the States by breaking free of England; fudged some aspects of monetary sovereignty in order to get agreement on the Constitution; spent several decades trying to resolve the division of fiscal, monetary and banking authority between the States and the Federal government; and finally established, after long legal battles, the primacy of the [latter],” Mundell writes.

Unsurprisingly, the US has since been unwilling to relinquish these hard-won powers.

At the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, whose participants outlined the rules for the post-war global financial system, economist John Maynard Keynes proposed the introduction of a basket world currency called the bancor, which would operate as legal tender around the world.

However, the US rejected this suggestion and the new global monetary order was instead centred on a single currency, the US dollar. The dollar, said the US, would be the only major world currency with a formal link to gold, while other countries could then manage their currencies’ exchange rates against the US unit.

Keynes’s idea has been resurrected. The outgoing Bank of England governor, Mark Carney, recently called for the introduction of a modern equivalent to the bancor in order to address what he sees as the negative side-effects of the outsized influence of the US currency.

But any reordering of the global money order is likely to meet with fierce resistance from those in charge.

“Dominant countries have the least to gain and the most to lose by giving up monetary sovereignty to a supra-national institution, and that is the reason why, historically, the dominant powers have always resisted international monetary reform,” Mundell says.

Seigniorage and negative rates

The way money is issued is a particular battleground for governments and competing, private sector issuers of money.

This is because the right to produce money was and is valuable in itself. In the past, when lords or sovereigns minted coins from bullion, they kept a portion of the proceeds for themselves.

“For a long period of history, a mint operated on the basis of a laundry,” writes historian John Chown.

“Private citizens would bring bullion to the mint. It would then be assayed, refined and struck into coins, and the citizen would receive in return coins equal to the value of the metal brought in, less a deduction known as seigniorage.”

Modern monetary systems don’t use gold or silver in any significant way. But the concept of seigniorage survives. It is now defined as the interest a central bank earns on the money it lends, or the return it receives on the assets it acquires.

“Members of the Note Circulation Scheme (commercial entities) buy new banknotes from us at face value,” says the Bank of England.

“Central banks will make ever larger losses”

“We invest this money in assets such as government bonds. We deduct the cost of printing and issuing banknotes from the income on these assets, and return the balance to HM Treasury. This income is called seigniorage.”

But the seigniorage model that worked for most of the post-Bretton Woods era has been turned upside down in the last decade. What happens when interest rates on short-term government bonds turn negative, as they have done across swathes of the financial markets, and the expected income stream becomes a steady source of capital losses?

Increasingly negative rates hit central banks’ money-printing revenues in two ways: first, they increase the demand for physical cash, and then they make you pay even more for producing it.

“In the eurozone, the cash-to-GDP ratio has already risen to 10%,” says Daniel Gros, director of the Centre for European Policy Studies, a think tank.

“Central banks will make ever larger losses as more and more institutions stash liquidity in cash instead of paying the European Central Bank (ECB), or the German government, to keep it safe.”

And the loss of income from printing money has already driven central banks to try to boost their income in other, much riskier ways, Gros says.

“Central banks have gone into maturity transformation of the kind usually done by investment banks: buying large amounts of long-term government bonds (financed by short-term deposits). This is called ‘quantitative easing’ (QE),” Gros writes.

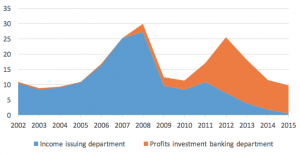

ECB income from issuing money (blue) and from investments (orange)

Last week the ECB doubled down on its efforts, announcing it would cut interest rates further into negative territory and restart its €2.6trn QE programme in order to head off an economic slowdown.

And central banks are trying to counter the increased hoarding of cash by making it physically more cumbersome to do so. For example, the ECB has now stopped issuing the €500 note.

Coining it in

It’s unsurprising that radical proposals for a new monetary system are emerging just as the traditional order is being turned upside down. But who gets to keep the money that traditionally went to the local ruler?

Facebook’s Libra Association has had no qualms in saying from the outset that it will pocket any future interest revenue if the digital currency ever gets off the ground.

“Interest on the [Libra] reserve assets will be used to cover the costs of the system, ensure low transaction fees, and support further growth and adoption. The rules for allocating interest on the reserve will be set in advance and will be overseen by the Libra Association. Users of Libra do not receive a return from the reserve,” Libra said in its white paper.

Critics from central banks, unsurprisingly, jump on the lack of accountability in the Libra set-up.

“Libra’s ecosystem is not only complex, it is actually cartel-like. To begin with, Libra coins will be issued by the Libra Association—a group of global players in the fields of payments, technology, e-commerce and telecommunications,” Yves Mersch, an ECB board member, said in a speech at the ESRB legal conference in Frankfurt on 2 September.

“The Libra Association will collect the digital money equivalent of seignorage income on Libra,” he clarified.

In his speech, Mersch linked central banks, the current guardians of the money supply, with the development of Western democracy.

“In 1787, during the debates on adopting the US Constitution, James Madison stated that ‘[t]he circulation of confidence is better than the circulation of money’,” Mersch said.

“It’s telling that Madison chose to use public trust in money as the yardstick for trust in public institutions—money and trust are as inextricably intertwined as money and the state.”

But with traditional seigniorage revenues from interest income disappearing and central banks under increasing fire for the negative side-effects of QE, the battle over money printing rights may only be beginning.

Don’t miss any more New Money Review content: sign up here for our newsletter

Support New Money Review on Patreon or in cryptocurrency