A major discovery by Satoshi Nakamoto, the inventor of bitcoin, was that you could ally game theory with computer science and cryptography and achieve a self-sustaining financial network.

But there’s a constant battle going on when cryptocurrencies are produced. The two sides involved in this cat-and-mouse game are the software designers writing the cryptocurrency rules, and the hardware designers and manufacturers seeking to gain the monetary rewards from mining.

Those manufacturing cryptocurrency mining equipment have been accused of keeping the best hardware for themselves, profiteering and of seeking to dominate cryptocurrency production. But efforts made by software designers to counter these centralising trends carry risks of their own.

In the early days of bitcoin, the activity of mining—the solving every ten minutes of a mathematical ‘hashing’ game requiring many billions of calculations—was open to anyone, just like a gold rush.

To demonstrate the point, in May 2013 writers at Wired magazine boasted that they had mined just over two bitcoins in ten days as part of a mining pool (in which miners collaborate to solve the hashing puzzle), using a small black box costing $274 and capable of calculating 5.5 billion hashes per second.

After mulling over whether they could exchange their two bitcoins for beer, the Wired writers decided that “the world’s most popular digital currency really is nothing more than an abstraction, so we’re destroying the private key used by our Bitcon (sic) wallet”. Those two bitcoins, to which access is now permanently lost, though worth around $200 at the time of the article’s publication, would now trade for $15,000.

“Cryptocurrency miner manufacturers are selling money-printing machines”

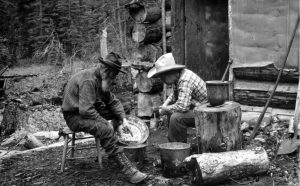

But just as gold mining is now performed not by old men in hats in a Californian forest, but by vast machines in open pits, these days only those able to invest in giant rigs of computers can profitably mine bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

The machinery needed to do this is highly specialised. A single Chinese-manufactured DragonMint 16T bitcoin miner, built around a specially designed chip called an Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC), retails for around $3,000 and can perform 16 Terahashes (16 million million hashes) per second.

ASICs stand out in cryptocurrency mining because of their single-purpose design: they merge in a single chip the computational and storage functions needed for the hashing calculation.

By contrast, traditional, general-purpose computer processors, such as central and general processing units (CPUs and GPUs), have to send data to the computer’s off-chip memory during the hashing calculation and then bring it back to the chip, resulting in slower overall performance. While CPUs and GPUs could be used to mine bitcoin in its early days, they are no longer fit for that purpose.

The mining of cryptocurrencies remains extremely lucrative. Bitmain, a Chinese mining hardware manufacturer and cryptocurrency miner, is estimated to have made up to $4billion in profits during last year’s boom.

But many say that a firm manufacturing cryptocurrency mining hardware does not—and by definition cannot—put its customers’ interests first.

In a recent blog post, David Vorick, lead developer of Sia, a blockchain-based cloud storage platform, explained why his company has recently decided to start manufacturing its own ASICs.

“Cryptocurrency miner manufacturers are selling money-printing machines,” says Vorick.

“A well-funded profit-maximising entity is only going to sell a money-printing machine for more money than they expect they could get it to print themselves. The buyer needs to understand why the manufacturer is selling the units instead of keeping them.”

Other firms are also attempting to break into the ASIC market for cryptocurrencies, currently dominated by Bitmain and another Chinese firm, Canaan Creative. Samsung announced in January this year that it was starting to manufacture ASICs. Intel filed a patent application in the US in March to develop a new hardware accelerator, designed to work with a mining chip.

But cryptocurrency designers haven’t sat idly by while a few hardware firms reap outsized profits.

In an attempt to keep mining from becoming too centralised, the software engineers writing some cryptocurrency hashing algorithms have sought to make them “ASIC-resistant”. In other words, the mining algorithms are specifically designed to allow a broader range of computer processors a decent chance of minting new coins in competition with ASICs.

“A policy of regular hard forking to change mining algorithms is risky”

One tactic is for cryptocurrency programmers to change their mining algorithm regularly in order to keep ASIC designers and manufacturers guessing.

For example, in February the team behind cryptocurrency monero announced that they would henceforth be modifying its hashing algorithm every six months to make the design of monero-specific ASICs more difficult. Monero underwent a hard fork in April to achieve this.

According to Sia’s Vorick, ASICs designed specifically to mine monero had achieved outsized profits during 2017.

“My sources say that they had been mining on these secret [monero] ASICs since early 2017, and got almost a full year of secret mining in before discovery. The return on investment on those secret ASICs was massive, and gave the group more than enough money to try again with other ASIC-resistant coins,” Vorick said.

A cryptocurrency analyst at an investment firm, who requested anonymity, pointed out the drawbacks of regular changes to a cryptocurrency’s mining algorithm.

“A policy of regular hard forking to change algorithms is risky,” he said. “You become much more vulnerable to attacks.”

For example, the computer processing power devoted to monero fell by 80% following its April hard fork.

Another way of increasing ASIC resistance is to make the hashing algorithm more complex. For example, a cryptocurrency called Verge, launched in 2017, was designed to use five separate hashing algorithms to help ensure democracy in mining.

However, this approach failed. It was revealed this week that Verge had suffered a hack, resulting in 35 million coins (worth around $1.7 million) being stolen, an accident apparently linked to the complexity of the mining process.

According to Daniel Goldman, author of the Abacus Crypto Journal, the Verge hacker was able to lower the difficulty of one of the five mining algorithms, use that to achieve majority processing power over the Verge network, print coins and disappear with them before anyone noticed.

“Manufacturing just inherently leads to centralisation”

Those seeking ASIC resistance in cryptocurrency design may be fighting a losing battle, according to Sia’s David Vorick. He argues that those bringing cryptocurrencies to market often overestimate their ability to stay ahead of those manufacturing mining hardware.

“The vast majority of ASIC-resistant algorithms were designed by software engineers making assumptions about the limitations of custom hardware. These assumptions tend to be incorrect,” he says.

Behind the scenes, there may also be murkier things going on, such as collusion between cryptocurrency designers and hardware manufacturers, says Vorick.

“We know of mining farms that are willing to pay millions of dollars for exclusive access to designs for specific cryptocurrencies. Even low-ranking cryptocurrencies have the potential to make millions in profits for someone with exclusive access to secret ASICs,” Vorick wrote in his blog.

Vorick predicts that the concentration of cryptocurrency mining power is inevitable.

“At the very best you get into a situation where there are two or three major players that are all on similar footing. Manufacturing just inherently leads to centralisation, and it happens across many different vectors.”

“If ASIC dominance is not necessarily a good thing, it may be a necessary evil.”

However, the dominance of mining by a few large firms may not necessarily be harmful, says one cryptocurrency analyst, who spoke on background.

“A contrarian view is that if mining relies on specialised hardware that’s difficult to acquire, and a 51% attack on a cryptocurrency requires a majority share of the hashing power, then it’s difficult to perform.”

“And in some ways the development of ASICs aligns long-term incentives: if a chip is designed only to mine a particular cryptocurrency, you don’t want to destroy that currency. If ASIC dominance is not necessarily a good thing, it may be a necessary evil.”

And, says the analyst, by comparison with the large efficiency gains made when cryptocurrency miners switched from using CPUs and GPUs to ASICs, there may be now a more level playing field in mining hardware.

“We’re probably running up against the limit in terms of the efficiencies you can squeeze out of ASICs. In the next few years ASICs running SHA-256, bitcoin’s mining algorithm, are likely to become commoditised, which is a net positive. Margins for miners will become more compressed and the market will become more equal again as a result.”

Very interesting article.

Just another thought: you can use any mining equipment profitability calculator to verify this:

Take the latest AntMiner S9i ($889) with 14 TH/s computing power. Ceterus paribus, you can expect to mine your first (!) Bitcoin after more than 40 years (!). That’s way too long for an individual with a single machine (since you have to pay electricity monthly, and so many things will change in the meantime, like difficulty, Bitcoin price, block reward, total hashing power). So you would have to purchase at least 40 x 12 = 480 of those miners to expect to mine, on average, one Bitcoin per month (or join a mining pool, with fees eating away at your profits). Few individuals will be will to make such an investment.

So we can see there is a certain danger of centralization of mining power also from that perspective.

Hi Alex, thanks for the comment and the interesting calculation. I suppose if there’s any trend towards decentralisation of mining it will only be among large-scale industrial players. Unless you have access to energy at a near-zero cost, as some people reportedly had in Venezuela for a while…or if a state actor does it to obtain a way around sanctions.