Last year commodity giant Glencore pocketed $1.3bn through a clever trade it made when oil prices briefly went negative.

Amidst the coronavirus shock to global trade flows, tankers idled, crude oil storage facilities were full and traders couldn’t give the world’s most important raw material away.

Glencore bought up the dirt-cheap crude, stored it in massive tankers it had recently acquired and sold the oil for a huge profit a few months later.

(the trader’s exploit is one of many similar stories recounted in Javier Blas’s and Jack Farchy’s excellent “the World for Sale”)

Location and financing in commodities

Often, the price for the future delivery of a commodity differs from that available when taking possession right now.

The divergence between the future price and the current (or ‘spot’) price reflects fundamental factors like storage, financing and insurance costs.

From the recent negative oil price we can see why storage matters—but why is the same true for bitcoin?

Bitcoin contango costs ETFs 8% a year

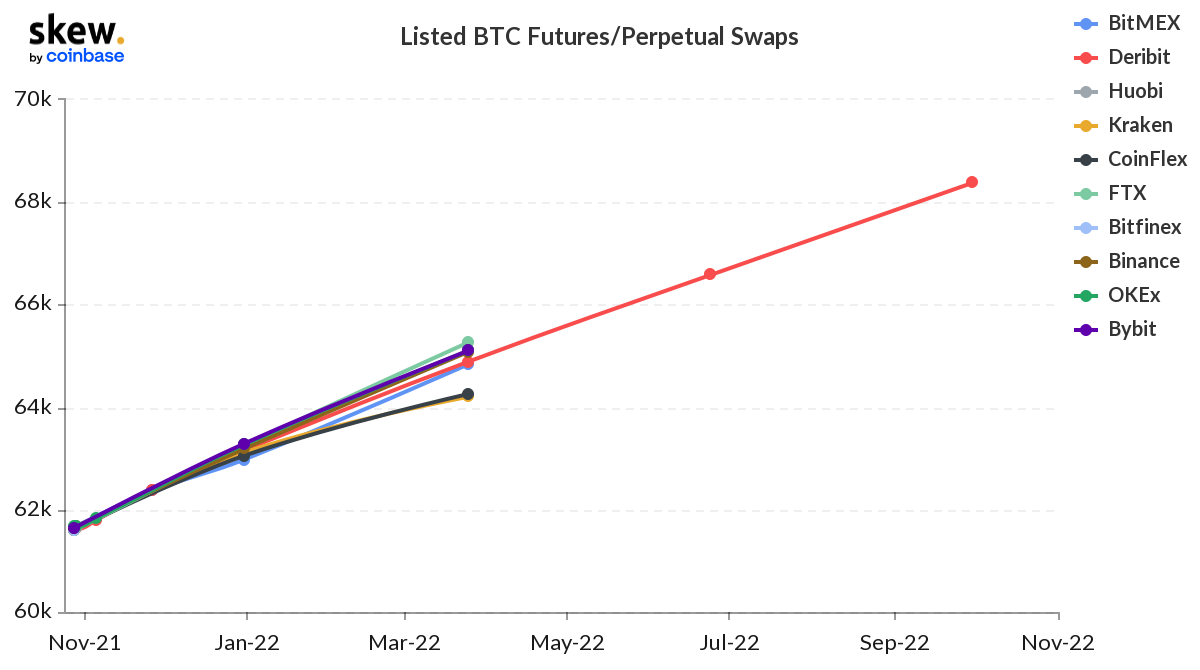

Recent data from Coinbase subsidiary Skew show that bitcoin futures follow an upward-sloping price curve (a situation known as ‘contango’).

The market price for trading the cryptocurrency one year in the future was around $7,000 per coin higher than the price for dealing right now (the ‘spot price), Skew’s data showed.

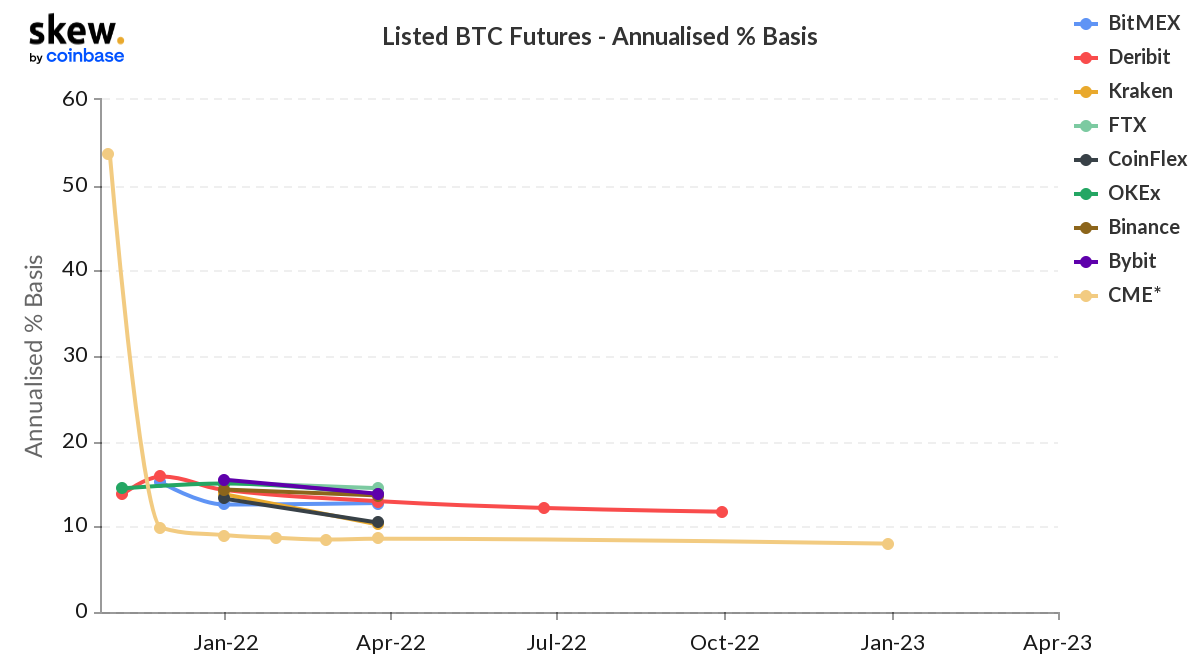

This difference between the cash price of bitcoin and its futures price—called the futures ‘basis’—can be expressed as an annual interest rate.

At the end of last week, according to Skew, the basis was around 15 percent at popular cryptocurrency derivatives exchanges, such as Binance, Deribit and FTX, and somewhat lower—around 8 percent—at futures exchange CME.

That basis is critical for anyone planning to buy a US-listed bitcoin ETF. For example, anyone holding the newly listed Proshares bitcoin futures ETF will experience the CME basis as a sizeable drag on performance—8 percent a year, on top of the ProShares ETF’s near-1 percent annual fee.

According to Mark Jones, short-term interest rate quant trader at B2C2, ETF demand explains some of the current pricing of bitcoin futures.

“There are two key market participants on the CME,” Jones told New Money Review.

“Traditional finance (‘TradFi’) is on the bid, largely in the form of the newly approved bitcoin futures ETFs, and they consume a very large percentage of futures open interest,” he said.

Five days after launching its bitcoin ETF on the Nasdaq exchange, ProShares applied to the CME for an increase in the position limits that limit its ETF’s holdings of bitcoin futures.

Two days later, the CME increased its position limits to accommodate both the ProShares Bitcoin Strategy ETF and another new bitcoin futures fund, the Valkyrie Funds Bitcoin Strategy ETF.

The other major category of bitcoin futures trader on the CME, said B2C2’s Jones, is firms specialising in futures/spot arbitrage.

“Crypto funding arbitrageurs trade both sides,” said Jones, “ensuring that the futures basis between centralised crypto exchanges and the CME is broadly in-line over the long run.”

Headline bitcoin futures basis is misleading

According to the B2C2 trader, the basis between futures and swaps traded on crypto-native derivatives exchanges and the CME futures is smaller in reality than the headline 7 percent a year.

“After accounting for the respective costs of funding margin, the CME futures basis is more aligned with crypto-native exchanges than it appears upon first glance,” Jones said.

He pointed out that CME imposes a relatively larger margin requirement—around 40 percent of the position size—than crypto-native exchanges, where the margin may be as little as 5 percent.

Credit risks probably explain the remainder of the basis, said Jones.

Cryptocurrency traders dealing with the CME have recourse to the exchange’s central clearing counterparty, which guarantees trades in case a market participant defaults.

There is no such central clearing in the crypto-native derivatives markets.

Instead, crypto derivatives traders rely on insurance funds offered by the exchanges themselves. These have been depleted in the past, forcing the exchanges to ‘haircut’—impose a mandatory reduction on—winning positions.

“Credit risk is harder to price,” said Jones.

“All else being equal, market participants would rather post margin and accrue profit and loss at the CME than at the crypto exchanges. This likely accounts for the remainder of the basis differential,” Jones told New Money Review.

The current bitcoin contango may not last, however: in early 2020 bitcoin futures prices regularly traded below the spot price.

Sign up here for the New Money Review newsletter

Click here for a full list of episodes of the New Money Review podcast: the future of money in 30 minutes

Related content from New Money Review

The wild world of crypto derivatives

Did Binance cover up May 19 liquidations?

Bitcoin arbitrage opportunities and risks